How to start right using a new telescope — a guide to basics you need to know, how to set it up, and what you can find in the night sky.

Gary Seronik

Maybe you just got a shiny new telescope to call your own. Congratulations — you could be on your way to making lifelong friends with stupendous, faraway things in your night sky. However, most of them are so far and faint that just finding and positively identifying them is the challenge — and the accomplishment! Whether your new scope is a long, sleek tube or a compact marvel of computerized wizardry, surely you're itching to try it out.

Before You Observe

Here are three crucial tips for starting on the right foot, to avoid frustrations and move quickly up the learning curve.

First, get your scope all set up indoors. Read the instructions, and get to know how it all works — how it moves, how to change eyepieces, and so on — in warmth and comfort. That way you don't have to figure out unfamiliar knobs, settings, and adjustments outside in the cold and dark.

Second, take the scope outside in the daytime and familiarize yourself with how it works on distant scenes — treetops, buildings — to get a good feel for what it actually does. For instance, you'll quickly find that a telescope's lowest magnification (the eyepiece with the longest focal length, meaning the one with the highest number on it) gives the brightest, sharpest, and widest views, with the least amount of the wiggles. The lowest power also makes it easiest to find what you're trying to aim at, thanks to that relatively wide field of view. So you'll always want to start off with the lowest power. Switch to a higher-magnification eyepiece only after you've found your target, got it centered, and had a good, careful first look.

Also: If the telescope has a little finderscope or a red-dot pointing device attached to its side, daytime is the easiest time to align the finder with the main scope. You need to do this. Aim the telescope at a distant treetop or other landmark, center it in the view, lock the mount's motions if the mount allows this, recheck that the treetop is still centered, and then look through the finderscope. Use the finder's adjustment screws to center the crosshairs (or red dot) on the same treetop. Then recheck again that it's still in the center of the main scope's view, in case you may have bumped it off in the process.

Third, plan to be patient. Spend time with each sky object you're able to locate, and really get to know it. Too many first-time telescope users expect Hubble-like brightness and color in the eyepiece — when in fact most astronomical objects are very dim to the human eye. Moreover, our night vision sees dim things mostly as shades of gray. Much of what the universe has to offer is subtle and, again, extremely far away!

But the longer and more carefully you examine something, the more of it you'll gradually discern. Astronomy teaches patience.

On the other hand, the Moon and the naked-eye planets are bright and easy to find! They make excellent first targets for new telescopic observers. Sky & Telescope's This Week's Sky at a Glance has suggestions for both telescopic and naked-eye viewing of the brightest stars and planets.

Here are some suggestions for starting off.

New-Telescope Delight: The Moon

The Moon is one celestial object that never fails to impress in even the most humble scope. It’s our nearest neighbor in space — big, bright, starkly bleak, and just a quarter million miles away. That's a hundred times closer than the nearest planet ever gets. An amateur telescope and a good Moon map can keep you busy forever.

Tonight (December 25, 2021) the Moon doesn't rise into good view until after midnight, and it's highest and best before the first light of dawn. But by January 4th or 5th the Moon returns to the evening sky as a crescent, growing thicker each night for the next week and a half. On January 8th it will be just about like the picture above (taken by an amateur through a small telescope): nearly first quarter (half lit), and high in the evening sky. After that it thickens through its "bulgy" gibbous phase, as more and more of the side facing Earth becomes sunlit.

The Moon will become full on January 17th. But the when the Moon is full we see no shadows being cast sideways to dramatize the mountains and craters. You'll always see lunar surface features best along the Moon's terminator, the lunar sunrise or sunset line. Look again at the photo at the top of this page. The terminator is where the low Sun in the lunar sky casts long black shadows even from low hills, mountains, and crater walls. The advancing terminator unveils new landscapes day by day when the Moon is waxing, then hides them in darkness day by day when the Moon is waning after full. In between at full Moon, the terminator lies all around the Moon's edge out of sight.

Bright Planets

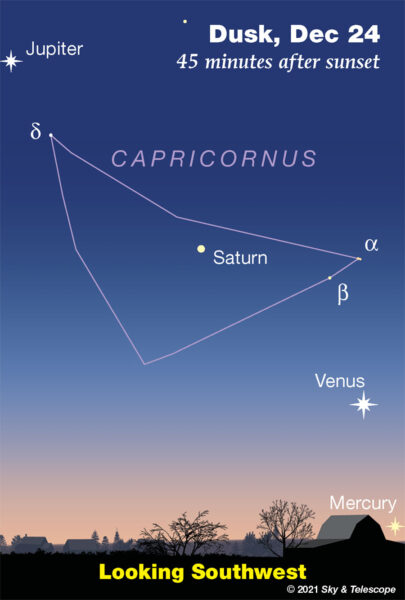

As it happens, your new scope has arrived at a special time for three of the bright naked-eye planets. Jupiter, Saturn, and brilliant Venus shine in the southwest in twilight, in a long diagonal line from upper left to lower right in that order.

Start early in bright twilight with Venus, because it's about to set. (In fact it's gone by twilight's end.) Right now Venus is going through its most dramatic phase: as a brilliant, very thin crescent, unusually large. What you're seeing is the edge of Venus's dayside. Its white cloud cover is dazzlingly lit by the Sun, which shines closer and brighter on Venus than it does on Earth. Watch day by day as the crescent thins further and the planet moves lower into the sunset glow. You'll probably lose sight of it in the first few days of January 2022.

Next, Jupiter! It's the bright white "star" much higher, far to Venus's upper left. In even the smallest telescope Jupiter's four pointlike moons show lined up on either side of it. They change configuration endlessly from night to night. Jupiter itself spins so fast (once every 10 hours) that it's not quite round, and even a small telescope will reveal this. And can you make out any of Jupiter's parallel cloud belts? They often darken or brighten, broaden or narrow, over a matter of months or years.

Between Venus and Jupiter is Saturn, much less bright. Yes, it has rings! Can you see the hairline black Cassini Division between the inner B ring and the narrower, outer A ring? And look for subtle cloud belts on the globe of the planet itself.

The other two bright planets? Mercury is very deep in the glow of sunset right now but will get a little higher, in better view, for the first half of January. Mercury is the smallest planet, farther from us than Venus and showing a dull gray surface, so you'll be doing well just to see its changing phase.

And Mars? It's very low in the east at dawn, currently faint and far on the opposite side of its orbit from us. It's so small and far that in a telescope it will just be a fuzzy orange dot. But wait till a year from now. In late fall 2002 and early winter 2003 Mars will be passing relatively close to Earth, inviting close examination for a few brief months. Did I say astronomy teaches patience?

More New-Telescope Sights

There's much more to the night sky than the Moon and planets, of course. Winter nights often bring crisp, transparent skies with a grand canopy of stars. But with so many inviting targets overhead, where to point first?

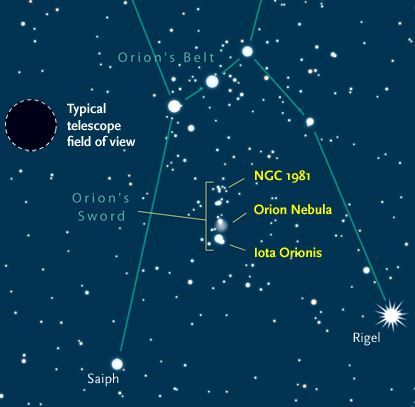

Here's a suggestion! The familiar constellation Orion climbs the southeastern sky in the evening these weeks. In its middle, look for the three-star line of Orion's Belt. The Belt is almost vertical as it rises in early evening. It turns diagonal (as shown in below) late at night.

Sky & Telescope diagram

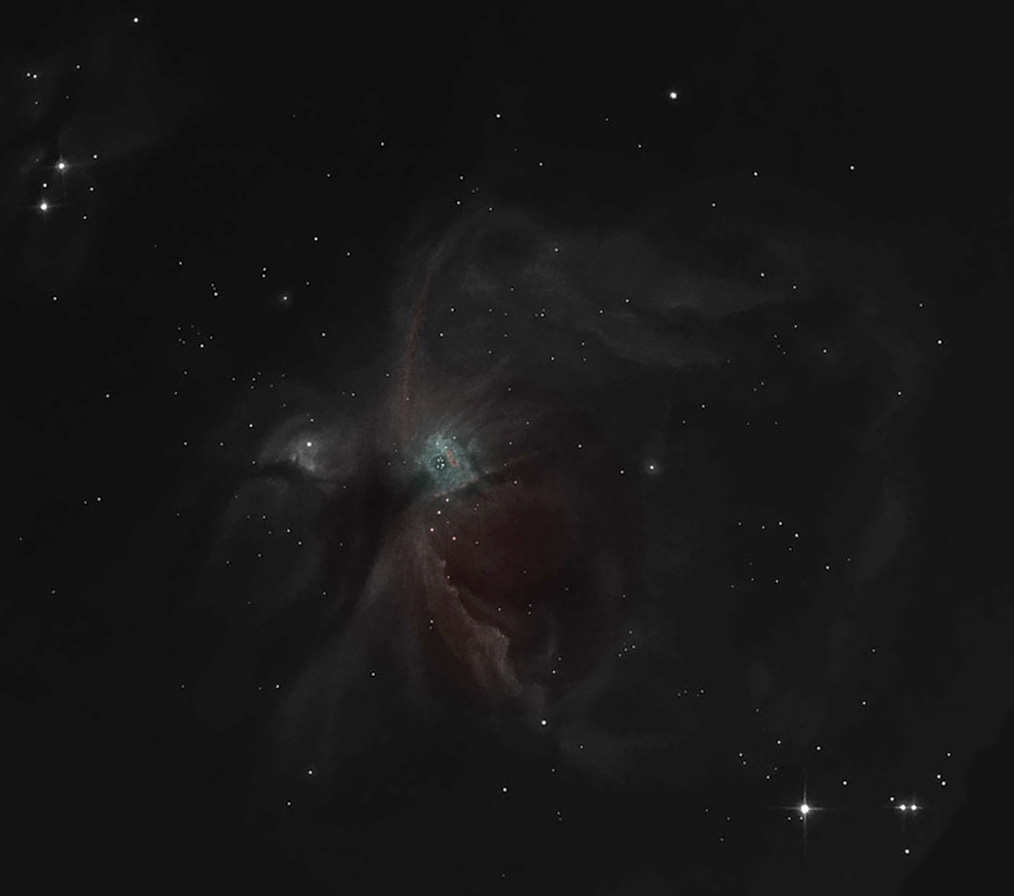

Just a few degrees south of the Belt (that is, a few finger-widths at arm's length) runs a smaller, dimmer line of stars: Orion's Sword. Within it lies the Orion Nebula, a luminous cloud of gas and dust where new stars are forming by the hundreds. It shows pink in most photographs, but to the human eye it's dim gray with a hint of green. The nebula is evident in any telescope once you get pointed at it, and so is the tight quartet of young stars near its center, known as the Trapezium. Astronomers refer to the Orion Nebula as Messier 42 (M42), and you'll see it labeled that way on star charts. Located about 1,400 light-years away, it's the closest massive star-forming nebula to Earth.

Dim objects like nebulae are best seen when the sky is moonless and really dark. The farther you can get out from under the skyglow of city light pollution, the better. But don't let light pollution dissuade you from finding what you can see from your own backyard! Choose reasonably bright targets to hunt, and develop the skills to find them and observe them carefully so you'll be ready to make the most of better conditions when the chance arises. For instance, the sky can be especially clean and dark the night after a storm passes through.

Howard Banich / S&T Online Gallery

Joshua Rhoades / S&T Online Gallery

You can use Orion's Belt as a pointer to other things. Extend its line far upward across the sky, by about two fist-widths at arm's length, and there's the relatively bright star Aldebaran, the orange eye of Taurus. Continue on by about another fist and you'll reach the little cluster of stars called the Pleiades. It's about the size of your fingertip at arm's length.

Through binoculars or a telescope at its lowest magnification, the Pleiades cluster shows dozens of stars. Astronomers have determined that the cluster has about 500 in all. Like other star clusters, the Pleiades are held together by their mutual gravity. This one is classed as an open cluster for the stars' relatively uncrowded arrangement. It's nearby as star clusters go, traveling through space as a swarm about 440 light-years away.

The Pleiades stars, astronomers have determined, began to shine only about 70 to 100 million years ago. This makes them mere toddlers compared to our Sun and solar system, which are 4.6 billion years old. M45’s youthful suns are astonishingly energetic. Alcyone (al-SIGH-oh-nee), the brightest, is at least 350 times as luminous as our Sun. Like the other bright Pleiads it gleams with an intense blue-white light — a sign that it’s unusually hot and massive.

Next Steps in Astronomy

To find much else in the night sky, start learning the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope — just as you need to know the continents and countries on a globe of Earth before you can pinpoint, say, Milan or Sydney.

For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy (ahem).

You'll also want a good, detailed star atlas (set of more detailed maps), such as the widely used Pocket Sky Atlas; a good deep-sky guidebook; and some practice in how to use the maps to pinpoint the aim of your telescope onto a something too faint to see with your eyes alone.

For more tips on skywatching and how to get the most out of your scope, see our Observing section and Getting Started section.

Whatever else, stick with it! Nobody is born knowing this stuff. Work your way into the hobby at your own pace, finding things to know and do and understand without worrying about everything you don't yet. That's really what life in a big universe is all about.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.