It was touch and go this evening. Rain was moving into California, forcing me to squint and strain to glimpse Mercury between the approaching cloud bands in the western twilight. Finally, it poked into view for a few brief minutes. I savored the moment, knowing that just an hour earlier the innermost planet had gained a new feature: an artificial satellite.

An artist's portrayal of the Messenger spacecraft after its arrival at Mercury.

NASA

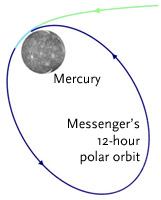

Some 96 million miles away, the Messenger spacecraft had fired its braking rocket and thrusters for nearly 15 minutes, a long burn begun at 8:45 p.m. EDT that slowed the hurtling craft by 1,929 miles per hour (0.86 km per second). A few anxious minutes later, an interplanetary communiqué arrived at the mission's control center at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory. The burn had gone flawlessly, placing the spacecraft safely in a looping 12-hour polar orbit.

It's taken more than 6½ years for Messenger to reach its new home away from home. Along the way was one flyby of Earth, two of Venus, and three of Mercury itself — all part of an intricate, carefully designed interplanetary billiard shot designed to deliver the biggest payload possible on a Delta II 7925 launch vehicle. As planetary scientist Mike Brown commented via Twitter, "Clearly, physics works really really well."

NASA's science team packed eight instruments onto Messenger (a contraction for Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging).

Messenger's polar orbit around Mercury ranges in altitude from just 120 miles (200 km) to about 10,000 miles (15,000 km).

NASA

But don't expect a glut of images to start flowing into the computers at mission control right away. For the moment, however, the ball is in the engineers' court to ensure that onboard systems are working properly. Most instruments won't be turned on until March 23rd, the cameras five days later.

The planned year-long study of all things Mercurian will begin in earnest on April 4th, along with gravity studies derived from the craft's motion and radio transmissions. According to project scientist Sean Solomon (Carnegie Institution of Washington), the first full-up release of results won't occur until May 10th.

In the meantime, check the mission website for progress reports and to see images of Mercury obtained during the trio of earlier flybys. You'll also get a kick touring the planet at close range by downloading this Mercury KML file for use with Google Earth.

Finally, don't miss the chance to spot the innermost planet making its best evening appearance of the year.

1

1

Comments

Michael C. Emmert

March 19, 2011 at 11:44 am

Good shot!

My agenda on the Messenger mission is to see if there is a twin to Caloris Basin. We got good images of that feature from the last Mercury mission several decades ago. I think it's a Lagrangoid scar.

But Mercury is a lot more interesting than that. I hope there's some way to find out something about the polar ice caps spotted by radar. It would be hard, because (of course) the icecap is in permanent shadow. The icecap was volatile fuel propelling the search for ice at our Moon's poles. It was tangible evidence that it COULD happen.

Y'know, frankly, it's kind of fun to hold a pseudoscience? So I'll post one here. The "icecaps" are actually made of sodium and potassium! Nice, conductive, high-radar-visibility volatile metal.

Well, we'll see.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.