Nothing warms my heart like vinyl records, wood stoves, and paper charts. In an increasingly digital world, a return to analog is as useful as it is whimsical. Join me tonight in exploring the sky in classic fashion, with an old-school telescope, as we brush up on our chart-reading skills.

The Project

The objective for this evening is simple: Observe eight objects plotted on the August Sky & Telescope monthly sky chart without any electronic aid. (Please excuse the irony of this being a blog post . . .) This project will build our knowledge of the sky, and the workflow presented makes finding the plotted targets a cinch.

Although this article has diagrams, the magazine’s chart is all you’ll need for our quest. Even if you’re a regular user of detailed maps, this “one-sky” approach is fast and fun.

If you don't subscribe already, here's your chance: Explore the skies every month with our monthly chart and observing tips!

The Gear

Cue up the B-sides and dust off the old scopes. I’ll be using a 1957 Fecker fork-mounted 4-inch Newtonian reflector, complete with green-speckle paint. The modern wide-field eyepieces will stay in the case, in favor of orthoscopics, a classic ocular with narrow, sharp fields. My 10×50 binoculars are brand new, though.

If you haven’t used your first telescope in a while, this is a perfect opportunity to put some miles on it. However, this aspect is strictly for fun, any equipment will do!

The Workflow

Navigating with charts may take a moment to get used to, but the benefits are many, and the satisfaction is rewarding. The strategy is to approach targets by gradually increasing magnification. I start with the chart, trace the constellation, scan with binoculars, aim with a finderscope, then observe with a telescope, using low power first.

Here are the eight objects we’ll be tracking down this evening:

- M29 (Open cluster, Cygnus)

- M27 (Dumbbell Nebula, planetary nebula, Vulpecula)

- M57 (Ring Nebula, planetary nebula, Lyra)

- M13 (Globular cluster, Hercules)

- M92 (Globular cluster, Hercules)

- M10 (Globular cluster, Ophiuchus)

- M4 (Globular cluster, Scorpius)

- M8 (Lagoon Nebula, emission nebula, Sagittarius)

Hop from Vega to M29

As darkness falls, I begin my journey at Vega, the brightest star of the constellation Lyra. A beauty to behold, it’s also an excellent opportunity to check the alignment of my finderscope after I have the star centered in the eyepiece, making adjustments as needed. Easy-to-find Vega also helps me put the chart in context.

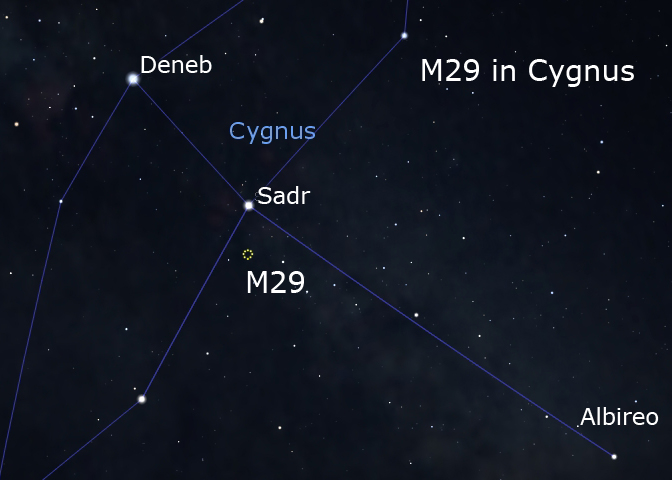

Referencing the map, I notice the open cluster M29 lurking nearby in Cygnus, off the coast of Gamma (γ) Cygni at the center of the Northern Cross. Grabbing the 10×50 binoculars, a quick scan of the region reveals a fuzzy patch roughly where the chart specifies, just the type of “false comet” Charles Messier would put on his list. The 6×30 finderscope doesn’t quite pull it in from my suburban location, but a bit of sweeping with the telescope and a low-power eyepiece yields a loose gathering of stars where they should be.

A mini squished Hercules shape glimmers in the eyepiece of the ‘57, not quite a dozen stars sparkling in a haze. Astronomy can be an art in subtlety, and with an abundance of open clusters in the summer Milky Way, this target isn’t an obvious lock. Nevertheless I jot a quick sketch in my logbook. It’s laughably basic, but later I can reference it to make sure I found what I was looking for. Plus, drawing observations helps pull out more detail and appreciation of the scene, committing it to memory and building “sky skill.”

Ancient Patterns: M10, M27, and M13

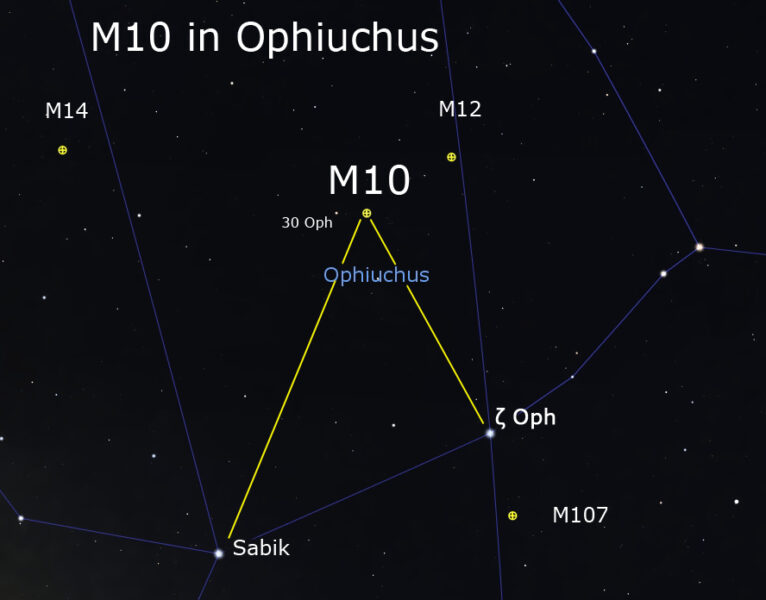

In the case of objects that lurk in dim corners of constellations, away from obvious markers, I see if I can find shapes and patterns to create some sky geometry to bridge the distance (especially if light pollution is washing out the fainter guideposts.)

M10, a lovely globular cluster in Ophiuchus, is an excellent example. First, I use the chart to familiarize myself with the sprawling constellation. Then, I notice how the cluster makes a nearly right triangle with Eta (η) and Zeta (ζ) Ophiuchi . Switching to binoculars, I scan the area, finding both M10’s tell-tale fuzzball, as well as a fairly bright field star, 30 Ophiuchi. Taking aim with the telescope, I snag the field star in the finder, slew around a bit, and bingo, there it is! The view in the 4-inch reflector reminds me of a bright galaxy in a big Dobsonian.

Try this method with M27, the Dumbbell Nebula. Before you start, study the chart and notice how it forms the missing fourth corner of a rectangle made by Beta (β) Cygni (better known as Albireo), Gamma Cygni, and Epsilon (ε) Cygni.

Moving to the zenith, the Great Globular Cluster in Hercules, M13, is at the level of the hero’s heart , just below Eta Herculis that marks his shoulder.

How good are your triangulation skills? Test them on M13’s overlooked neighbor, the globular cluster M92, which forms yet another triangle with Pi (π) and Eta (η) Herculis.

Easy Pickings: M4 and the Ring Nebula

Conversely, clusters like M4 in Scorpius offer a different approach. Antares, or Alpha (α) Scorpii, glares like a ruddy eye in the south on our chart, and M4 hangs just to the right of the star. Start your search on the “rival of Mars” for this summer favorite, panning west to snag the globular cluster. (They both barely fit in my low-power view with the f/8 reflector. Your mileage will certainly vary.)

M57, the famed Ring Nebula, offers a similarly easy aim, lurking roughly halfway between the two stars that mark the southern end of Lyra’s parallelogram (Gamma and Beta), although binoculars are hard-pressed to confirm the target.

Can’t Miss: Lagoon Nebula

Although the process is simple, it's not always easy. Don’t fall into the “HGTV Trap” when out under the stars. Home improvement shows conveniently omit the hours spent in the plumbing aisle, and astronomy articles can present a deceptive ease. Enjoy the process of learning while you’re observing, and go at your own pace.

Should the tricky star-hops stymie you, there are some deep-sky targets that are visible with the unaided eye: If the Milky Way can be seen from your site, the Lagoon Nebula (M8) on tonight’s list fits the bill. Simply look south and notice M8 as a glimmering patch in the steam from the Teapot of Sagittarius. (With any luck, you’ll miss and see some other treasures in the neighborhood, too!)

Before this Record Spins to an End

Armed with simple equipment, a red flashlight, and a one-page chart, we’ve visited some of the season’s showpieces in a refreshingly wire-free manner.

Moreover, this process can be fast, letting you take advantage of “sucker holes” (partial clearings in the sky) to snag quick views before the clouds close the curtain on the evening's festivities. Tonight was no exception: A surprised rainstorm chased me indoors minutes after this report was logged!

Try your own variations on the trip: perhaps with binoculars, or, when you get comfortable, leave the chart and flashlight inside, relying only on memory. Build on your skills by noting and remembering where you aim. Take notes, sketch observations, and most importantly, have fun as you relish celestial navigation. Catch ya on the flip side!

Josh Urban observes in an obscure part of Maryland, where he can hear the crackle of vintage recordings on nights when the clouds are as thick as buffalo plaid.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.