Neptune, planet of intrigue, captures our attention as nights begin to chill.

NASA

Think of a blue planet. Earth, right? But there's another one — Neptune. Every time I see it in the telescope I marvel at its blueness. I like to imagine it as Earth viewed from afar.

I got an eyeful of the planet recently in a 24-inch Dobsonian at the Minnesota Astronomical Society's annual Northern Nights Star Fest. I hung at the eyepiece for many minutes contemplating the tiny aquamarine disk and its "stellar" companion, the moon Triton.

Neptune, currently the Solar System's outermost planet, reached opposition on September 10th at magnitude 7.8 in Aquarius. It's a bone-chilling 4.3 billion kilometers from Earth, equal to about 4 light-hours. If you point your telescope at the planet at 10 p.m. local time, you'll see the light that left it at 6 o'clock when you sat down to dinner.

Stellarium

Neptune climbs high enough in the southeastern sky for a good look by 10 o'clock local time in mid-September and by 9 p.m. at the end of the month. You can easily spot the planet in a pair of 50-mm binoculars from the outer suburbs and countryside and watch it creep westward over the next few months in retrograde motion. Telescopes 3 inches and larger give the best views, revealing Neptune's tiny disk and blue coloration, which to my eye looks noticeably bluer than Uranus's. I compared the two ice giants that night in the 24-inch and crosschecked with another observer. We both agreed that Uranus looked more yellowish, lacking the intensity of Neptunian blue.

Bob King

Given Neptune's tremendous distance it amazes me that we can make out a disk at all. Only 2.4″ (arcseconds) across, it's perfectly obvious at a magnification of 150× in good seeing. When seeking the planet in a field littered with similarly bright stars, a careful observer can still pick it out from the crowd because Neptune lacks the shimmer of a star.

Finding it shouldn't be much of a problem this season because it hovers near 4th-magnitude Phi Aquarii for many months. Phi lies 3° due north of what I like to call the Crooked Finger asterism, a tidy arrangement of three 4th-magnitude stars all named Psi — Psi1, Psi2, and Psi3 Aquarii.

Part of me wishes I'd written about Neptune a week ago because it passed incredibly close to Phi, just 12″ to its south on the night of September 6–7. By September 11th, Neptune's separation increases to 9′ (arcminutes) — still tight — and the planet remains within 1° of the star through October 15th. Finagle Phi into the low-power field of view and Neptune won't be far away.

The blue planet will pass this way again, skimming just just 2.3′ north of the star on February 10, 2020. This detailed pdf map will help you track it into 2020.

Besides a dot's worth of earthy blue, what else is there to see of Neptune? As amateurs, we always carry a mental fanny pack of information to help us understand and appreciate what we see in our telescopes. Neptune's color is due to the presence of methane in its atmosphere. Methane absorbs red light and reflects back blue. The planet takes 164.8 years to go around the Sun once, making it impossible to see one revolution of Neptune in our lifetime, yet another reminder of how short life really is.

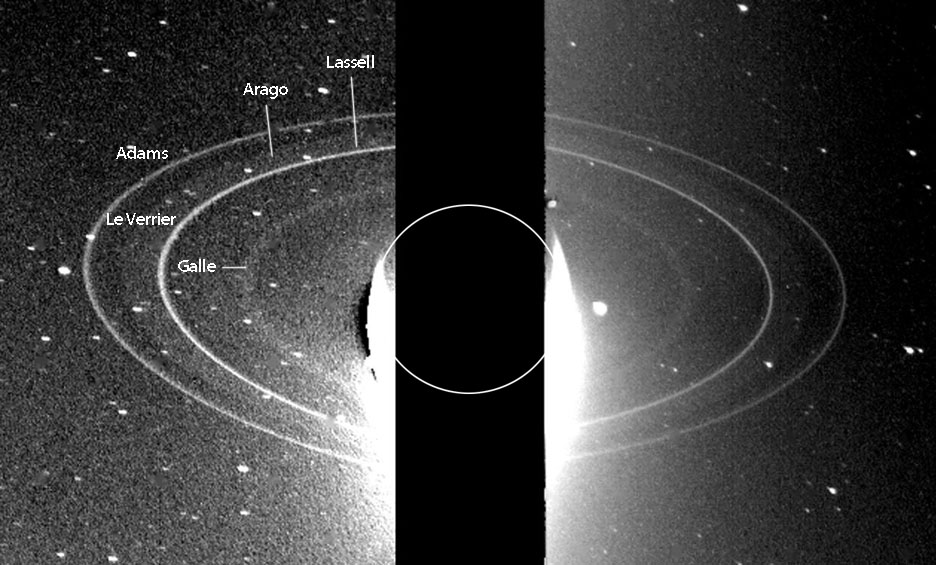

NASA / JPL

Although the fourth largest planet, Neptune ranks second in gravitational pull after Jupiter due to the hot, dense mixture of liquid water, methane, and ammonia that fills it interior. The fluid is so compressed that deep within the planet scientists are reasonably certain that some of it congeals into a rain of diamonds that collect around Neptune's rocky core. The heat released from the infall helps to warm the planet and may provide the energy to power the winds and storms that lash its upper cloud decks.

Neptune's axis has a tilt of 28°, very similar to Earth's, which means it has seasons — even though each one lasts more than 40 years. Neptune is a cold, dark, and windy place and like the other outer planets perpetually cloudy. Average cloud-top temperatures hover around –353°F (–214°C) as near-supersonic-speed winds whistle by at 1,300 mph (2,200 km/h) day and night.

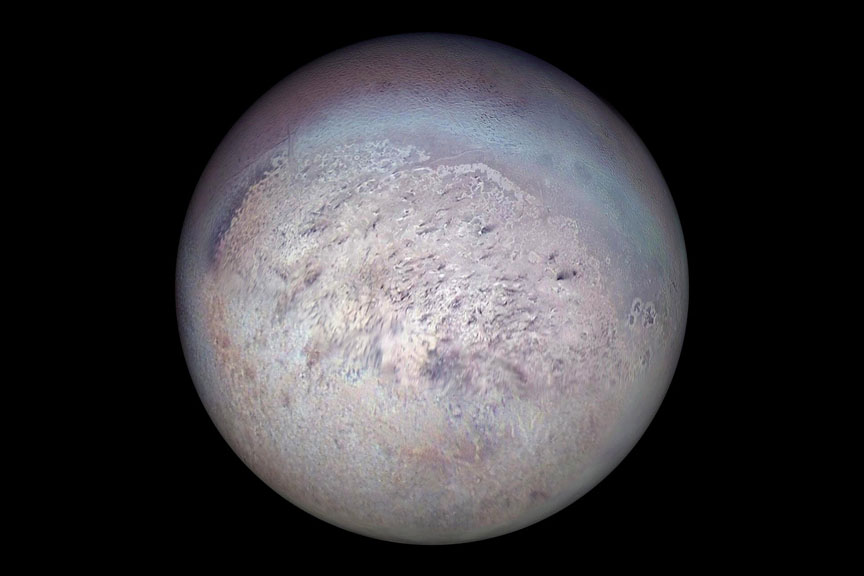

Neptune's extended family includes 13 known moons and one provisional moon. One of the most interesting is Nereid, the third largest at 170 kilometers across and the last discovered from Earth. Voyager 2 spied the remainder when it flew by the planet in the summer of 1989. Nereid has an extremely eccentric and long orbit; its distance from Neptune varies from 5.5 million to 9.7 million kilometers over the course of its 360-day orbital period, nearly one Earth year.

NASA / JPL

Most of us will never see Nereid because it's a 19th-magnitude speck, but an enterprising astrophotographer might consider it a worthy challenge. The moon is currently 7.5′ due east of the planet, close to Phi Aqr. Much easier to see and perfectly doable for anyone with a 10-inch telescope (maybe even an 8-inch) on a night of decent seeing is spotting Neptune's largest and brightest moon, Triton. Shining at magnitude 13.5, Triton comes into view when you magnify the scene 200× or more. Look for a tiny spark of light and use averted vision, which helps pop it out of the planet's glare.

Stellarium with additions by the author

The moon is farthest from the home planet and easiest to spot at northern and southern elongations. At those times the two are 14.5″ apart. When east and west of the planet the separation shrinks to about 9″. On September 11th, it reaches northern elongation and swings to southern elongation on September 14th. Triton moves fast enough that its orbital motion can be detected in about two hours. Take a look early and then return before you finish up for the night, and you'll see Neptune's big-boy gravity at work.

I like the eighth planet because it breaks up a night of deep-sky viewing, which often means galaxy hunting this time of year. A splash of hot sauce on that chicken sandwich as it were. With the big planetary celebs Jupiter and Saturn heading west, Neptune will be there for you, teasing you to look and challenging your assumptions about featureless dots.

12

12

Comments

Rod

September 11, 2019 at 12:36 pm

Bob, I was out viewing Neptune and Phi Aquarii red giant star on the 7th from 2200-0030 EDT. I enjoyed views of both at 71 to 111x views in the eyepiece, my barlow lens fogged up 🙂 Anthony in California, and I in Maryland, both noticed the color combination of bluish Neptune and the red giant star. We posted some comments at the Sky this week report. My 90-mm refractor at 179x and 200x has no problem with Neptune as a small, bluish disk in the eyepiece - so long as my eyepieces and barlow lens do not fog up 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 11, 2019 at 1:39 pm

Hi Rod,

Thanks for sharing your observation. You're right! Neptune and Phi make a nice color contrast.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe Stieber

September 11, 2019 at 1:49 pm

I’ve been following Neptune ardently since 2008 when it was near the row of 42, 44 and 45 Cap, just north of Deneb Algedi and Nashira at the eastern end of the Capricornus stick figure. Every yearly apparition, after I got my bearings from a chart for the first few times (since it shifted position from the previous year), I could follow its movement without a chart for the rest of the apparition. Every time I’m out observing, I take a look at it, at a minimum with binoculars. With my relatively new 16-inch Dob, it shows a really nice blue disc. I had it set up for a public event at a local nature center a couple of weeks ago and a number of people had a view of the blue disc for the first time. I can appreciate how great Bob’s view must have been in the 24-inch! I still need to buckle down and look for Titan though — as weather permits. I was all set to watch the close passage of Neptune by Phi Aqr overnight on Sept 7 (I made an hourly table of the changing separation and altitude), but it was cloudy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

September 11, 2019 at 2:16 pm

I've been enjoying following Neptune through 10x42 image-stabilized binoculars from light-polluted San Francisco. My preferred star hop starts at the water jar of Aquarius, southeast to distinctively orange Lambda Aquarii (Neptune was hanging out here last year), then a dog-leg to Phi Aqr. If I see the three Pi's I know I'm a little too far south.

I haven't seen Neptune through a telescope at higher magnification yet this year. I need to do that!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe Stieber

September 11, 2019 at 2:47 pm

Anthony -- I too have been using the Water Jar as a starting point for the past few years, dropping down to Lambda and now sliding east to Phi. However, as Neptune has drifted increasingly eastward, and if I'm in the darker NJ Pines where I can see them with unaided eyes, I'll just start at the little arc of Psi 1, 2 & 3 and move up. Note: Pi is in the Water Jar (it can be confusing with Pi, Phi and Psi all involved near Neptune).

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe Stieber

September 11, 2019 at 2:53 pm

I just noticed. The chart at the top of the page has an error. Psi 1-2-3 are mislabeled as Pi 1-2-3.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe Stieber

September 11, 2019 at 2:56 pm

I should have looked more closely! Phi is mislabeled as Psi. I said it was confusing!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 11, 2019 at 4:16 pm

Hi Joel,

Sorry, that was an uncorrected older map. It's now fixed. As for Phi, that actually was the correct symbol — at least the one my keyboard offered. Phi can be written in a couple different ways as it turns out. But to eliminate any confusion I substituted it just now with its other guise. Thanks!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

September 11, 2019 at 6:20 pm

Thanks to you both. I never looked up the Bayer letters for that little three-star asterism, but I know I'm too far south when I see it. Now I know their three Psi's.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe Stieber

September 11, 2019 at 9:27 pm

My authoritative reference for the Greek letters was S&T's Pocket Sky Atlas, chart 76, where Pi (π), Phi (φ) and the Psi (ψ) threesome were all on the same page. There's also a Greek alphabet table on page xii. 😉

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 12, 2019 at 4:39 pm

Joe,

Pi, Phi and Psi — now that is a mouthful 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Walter Clayton

September 13, 2019 at 6:36 pm

Near the Psi Aqr group is one of my favorite galaxies, NGC 7606. It's one of those galaxies i go back to year after year. I first saw it from my front yard 40+ years ago, and, every fall I check on it.

Not a spectacular galaxy by any means, but, I still look.

Walter Clayton

s/v Always Home

Charleston, SC (today anyway)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.