The near-term haze of climate disasters obscures our possible futures. But long-term trends leave room for optimism.

Alex Wong / Getty Images

This may be my last Cosmic Relief column, at least for now: I’ve accepted the position of Senior Scientist for Astrobiology Strategy at NASA, which sadly will eat up my writing time. Contributing to S&T has been a great gig, and I truly appreciate all the wonderful feedback from readers over the years.

I just re-read my first column, from January 2009. In it I describe a conversation with my father about the future, juxtaposing his pessimism, at age 80, with the hopeful perspective I gained from the SETI conference I was then attending. He felt that humans were losing the “race between education and catastrophe,” as H. G. Wells warned in 1920. My dad worried about his grandkids growing up in a world harmed by climate change.

I shared his concerns, but these were counterbalanced by my enthusiasm about the imminent launch of the Kepler spacecraft, which promised to reveal the numbers and demographics of exoplanets. Kepler’s results would enable us to do comparative planetology. By putting our solar system in context, we could learn more about how planets work and how life integrates into planetary functioning, equipping us to better manage our role on Earth.

My father lived another 12 years, long enough to savor Kepler’s dramatic confirmation of our most optimistic speculation that planets are, in fact, ubiquitous in the universe. Up until his death three years ago at age 92, his foreboding was leavened by his love of the natural world, embodied in bird-watching forest walks and, as his mobility declined, in enjoying online bird-cams and Hubble and Mars-rover images.

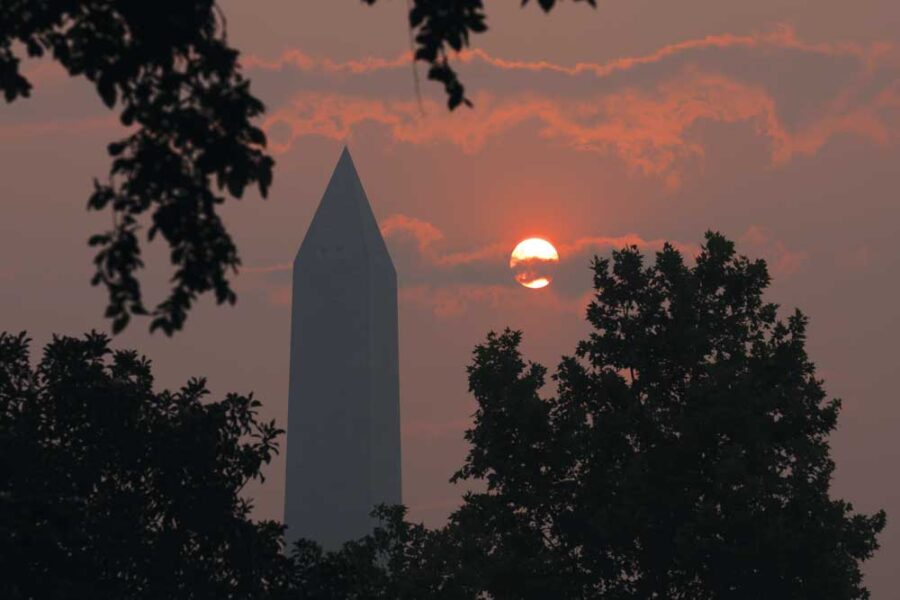

As I write this, the skies over me in Washington, D.C. look strangely Martian, with the Sun oddly dim and red. The haze comes from wildfires burning out of control in Canada. But I don’t “blame Canada” (as the South Park song goes). We are all to blame for Earth’s changing atmosphere. As the look of our skies becomes more Martian, the temperatures are becoming more Venusian. Since I wrote that first column, the CO2 in our atmosphere has risen about 10% and now hovers at 422 parts per million. Heat records are being broken at a frightening pace.

The faint silver lining to accelerating climate disasters is that the threat is no longer as abstract. Most nations can be counted on to act in their own perceived self-interest. Fearing their own climate calamities will help major powers move beyond fossil fuels.

Some trends are bending in our favor on that front. The costs of alternative energy have fallen faster than anyone predicted 10 years ago. We’re starting to wean ourselves off fossil fuels — far too slowly, but we can still avoid worst-case scenarios. We’ve already passed peak human birth rate, and later this century population curves will start to arc downward, relieving pressure on nature. Carbon emissions, too, will likely soon peak and begin to decline.

I believe we’ll muddle through this century, learning lessons the hard way but in time forging a sustainable global society in which our technological skills, perhaps aided by machine intelligence, integrate with natural systems rather than run roughshod over them.

Another Wells quote comes to mind: “Our choice is limited: either the whole universe or nothing.” I still believe we’ll choose the whole universe, and that eventually we’ll move out to live among the stars, not in a hurried escape from a ruined Earth but as a diaspora of our descendants who’ve learned what it takes to live and work well within the limits and cycles of planetary systems.

This article originally appeared in print in the November 2023 issue of Sky & Telescope. Subscribe to Sky & Telescope.

2

2

Comments

Sandy82579

August 15, 2023 at 10:43 am

First of all, fossil fuels will always be needed until fusion energy is commercialized, because sometimes the wind doesn't blow and the sun doesn't shine. Then there's the disaster in Arizona and Nevada. Solano and Ivanpah continue to underperform because of clouds, jet trails, and weather, not to mention they are ecological disasters. Ivanpah in particular kills 10s of thousands of birds a year, uses 525 million cubic feet of natural gas every year to start up in the morning(?), and it only generates 133 Mw. A typical fission nuclear power plant generates 1,200 Mw, all the time, day and night, and doesn't kill birds or use natural gas.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

August 15, 2023 at 6:30 pm

Dear Dr. Grinspoon -- Congratulations and best wishes for your NASA gig! Thank you for all the cosmic relief. And please accept my belated condolences for the loss of your father. I just read his NY Times obituary. Quite a life! He sounds like a lovely person.

I don't share your optimism that whiz-bang techno fixes in general and astrobiology in particular will save humanity, but we share the same urgent concerns for life here on Earth. Short-sighted greed, ignorance, and cruelty are already causing the sixth mass extinction of life on Earth, and the climate system is tipping into chaotic disruption. By all means let's keep looking for life elsewhere in the cosmos, but let's not expect that aliens are going to teach us anything we don't already know. Live within your means. Be kind. Give more than you take. Consider the effects of every action on the next seven generations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.