One of the smallest constellations in the sky hosts one of the richest concentrations of dark nebulae. Join me for a dip in these dark pools from which the next generation of stars will be born.

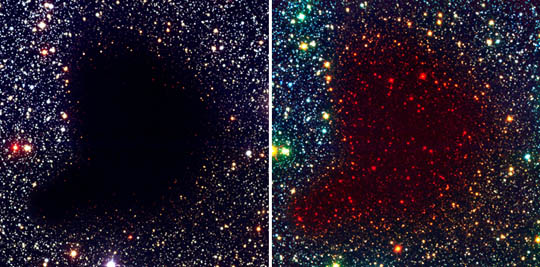

ESO

If the ducks in the Wild Duck Cluster (M11) in the constellation Scutum should ever decide to seek refuge, they'll have their choice of many a dark and shapely pond. The entire region is saturated with them — inky, starless areas of all shapes and depths that dot the Shield like Minnesota's 10,000 lakes.

Of course we're talking about dark nebulae, enormous clouds of interstellar dust and gas that blot out the more distant stars, creating the illusion of holes or in the starry fabric of the Milky Way. They're made of materials similar to those of bright nebulae like Orion or the Lagoon, but lack a nearby star or stars to set them aglow.

Although the density of these dark clouds is only on the order of 100-300 molecules per cubic centimeter, it really adds up over a depth of several light years or more. Some dark nebulae appear nearly opaque without a single star to relieve the gloom.

ESO

A single visible star, that is. Deep inside, where hydrogen, carbon dust, water ice, and other compounds feel the contractive force of gravity strongest, new stars are forming that only radio and infrared telescopes can see. Dark nebulae are crucial to the life cycle of the universe because they provide the raw materials for the next generation of stars and planets. It may appear you're staring into nothingness, but nothing could be further from the truth.

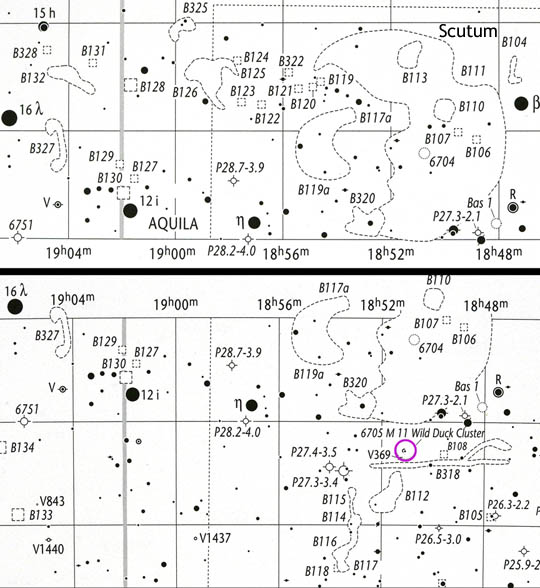

Bob King

Feel free to soak up M11's stellar glory. It's one of the richest, most compact open clusters in the sky. Every summer, I regularly drop by for a starry high. The cluster serves as a point of departure for our journey into darker realms. Within a 3° radius of the flock there are nearly 40 cataloged dark nebulae, enough to occupy several nights of observing. Most are from American astronomer E. E. Barnard's catalog of dark nebulae, hence the "B". Barnard's observations and photographs of these then-mysterious voids were instrumental in uncovering their true nature.

All are found either within or bordering the Scutum Star Cloud, a powder puff-like brightening in the band of the Milky Way in the constellation Scutum just below the tail of Aquila. I could list and describe each one, but we'll concentrate instead on the highlights and leave the rest as surprises.

Used with permission: Wil Tirion, Barry Rappaport, and Will Remaklus. Uranometria 2000.0. Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, Inc., 1987-2012.

From outer-ring suburban and rural skies, the largest of the dark nebulae, B111, is visible with the naked eye as a dark indentation along the star cloud's northern edge. In 10×50 binoculars, this 2° x 2° clot of dust stands out in striking contrast to the distant starry background immediately north of M11. Careful viewing will reveal mottled textures and even blacker clouds like B110 and B113 within it bounds.

Kidney-shaped B119a, just half a degree to the east, was lower contrast but I had no problem viewing it once I knew just where to look. Further east and north we bump into B125-6, a pair of low contrast nebulae, while 2.5° west of M11 you're sure to be impressed by the jagged, dark B103, an expanse of near-emptiness almost 1° across.

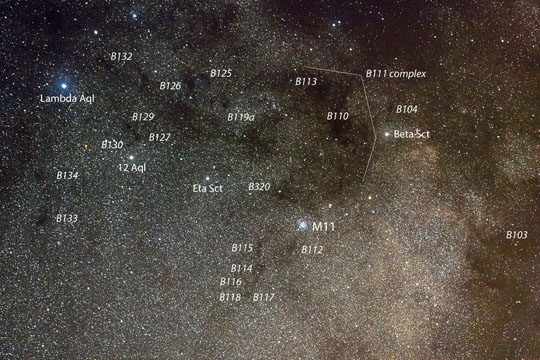

Koen van Gorp

After seeing what I could in binoculars I turned to my 15-inch (37-cm) reflector to hunt down the smaller nebulae. While a large telescope will make the starry backdrop brighter and improve a dark nebula's contrast, low magnification and wide field of view are just as important. I used 64× and wished for half as much! The more starry space you can put around a dark nebulae (to a point), the easier it is see. Wide-field instruments in the 4- to 8-inch range are ideal for the hunt.

Proceeding south of M11 we first encounter B112, which appears as a weak 20′-wide shadow cast across the glowing stellar backdrop. But it was the strung-out series of B114 through B118 that really caught my attention. Start at one end and follow the dark lumps one to the other. The whole complex bears a curious likeness to a snake gorging down a big meal. It was one of my faves.

I couldn't make out the long, prong-like shape immediately south of M11, but little B108 was dimly seen as a small vacuity.

Koen van Gorp

Nothing prepared me for the storm clouds of B111 to the north. Here the sky suddenly went "overcast" just the way I've seen a clear night swept away by incoming clouds. Between the gritty rifts, rare islands of starlight bravely rose from the inky depths. As you sweep back and forth across the region, the sense of impenetrable dust becomes palpable. B320 was especially dark with a single 8th magnitude star in its center.

Other goodies included B125 and B126, two pools of darkness separated by a narrow, starry lane, and the trio of B127, 129, and 130, the first two relatively easy, the last being rather difficult. Keep heading east and you'll arrive at the puffy, gray-black B134 and B133, a rounded globule that's one of the darkest and easiest of the bunch.

Stellarium

If I might suggest one more — don't miss B103. Go back to M11 and guide your scope some 2.5° to the west. Along the way, you'll blast through lots of stars until you encounter the nebula. Few transitions offer such a profound feeling of passing from light into darkness. Try it, I think you'll be astounded.

I've listed a selection of the best of the darkest in the table below. Opacity or the degree of blackness in a nebula ranges from 1 (not very opaque) to 6 (inky). Enjoy exploring the dark side of the universe!

Additional links for more information:

* Barnard's Catalog

* Uranometria 2000.0 Atlas

* Koen van Gorp Images

| Name | R.A. | Decl. | Dimensions | Opacity | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B111 | 18h51m | –5° | 120′×120′ | 3 | Large, spectacular with several very dark patches |

| B103 | 18h39m | –7° | 4′ × 4′ | 6 | Like a storm cloud, dark, considerably larger than listed size |

| B119a | 18h55m | –5° | 30′ × 30′ | 3 | Nice shape but lower contrast |

| B125 | 18h58m | –4° | 9′ × 2′ | — | Vague in binoculars; better in the telescope. Paired with B126 |

| B126 | 18h59m | –4° | 8′ × 8′ | 4 | Blends with B125 in binoculars |

| B112 | 18h51m | –7° | 20′ × 20′ | 4 | Moderate contrast, fairly easy |

| B114-118 | 18h53m | –7° | various | 3-6 | Fun to see string of dark blobs oriented N-S |

| B108 | 18h50m | –6° | 3′ × 3′ | 3 | Best visible by tapping the scope to make it pop. Small. |

| B320 | 18h53m | –6° | 15′ × 15′ | 4 | Prominent dark block at south end of B111 complex |

| B129 | 19h02m | –5° | 5′ × 5′ | 5 | Small but black, obvious |

| B127 | 19h02m | –5° | 4′ × 4′ | 5 | Similar to B129 but not quite as black |

| B130 | 19h02m | –6° | 7′ × 7′ | 5 | Low contrast, saw best with averted vision |

| B134 | 19h07m | –6° | 6′ × 6′ | 6 | Round, fairly easy, moderate contrast |

| B133 | 19h06m | –7° | 10′ × 3′ | 6 | Very dark, easy. Shape rounder than dimensions would indicate |

Planning ahead? The 2016 Sky & Telescope Observing Calendar is now available!

4

4

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

July 15, 2015 at 7:17 pm

Thanks Bob. The table is a wonderful summary. I printed it out. Assuming we have clear skies, I'll spend some time looking for dark nebulae at my club's monthly star party this Saturday night.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

July 16, 2015 at 1:14 am

Anthony,

I think you're really going to enjoy these. A dark sky and moonless night are ideal. Looks like we have that through about the 21st or 22nd for this month's window.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

July 16, 2015 at 3:43 am

Great article!

Definitely, I must check what is within reach of a 50- and 70-mm binoculars east of B119a. All those dark spots and blobs always seemed to blur together but actually I never tried to focus only on that region.

And as for B103 - I fully agree: the view of this dark curtain is one of the greatest sights in the sky!

PS

It's been three or four years since I observe dark nebulae and it's good to know there are more dark-side walkers 😉

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

July 17, 2015 at 6:37 pm

Thanks Panasmaras! I remember stumbling on this region some years back. Right away I went in search of charts and have spent several happy hours "dark-side walking" as you say. Glad to hear your impression of the amazing B103.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.