FRIDAY, DECEMBER 29

■ This is the time of year when M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, passes your zenith soon after dark (if you live in the mid-northern latitudes). The exact time depends on your longitude. Binoculars will show M31 as a small, dim gray, elongated glow just off the knee of the Andromeda constellation's stick figure. See the big evening constellation chart in the center of the December Sky & Telescope.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 30

■ The brightest asteroid in the sky, 4 Vesta, is just past opposition and creeping from the top of Orion's Club toward Zeta Tauri, the dimmer horntip of Taurus. Binoculars will show Vesta easily at magnitude 6.5. But you'll need a fine-scale finder chart to tell it from the other faint pinpoints in the area! Use the chart with Bob King's article Vesta Sets Sail Across Orion.

Vesta will pass 0.2° from Zeta Tauri on the nights of January 7th and 8th. Then on January 11th, 12th, and 13th it will cruise about ½° south of the dim Crab Nebula, M1.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 31

■ After the noise and celebration at the turning of midnight tonight, step outside into the silent, cold dark. The waning gibbous Moon will be shining high in the east, with the Sickle of Leo floating about a fist at arm's length above it. In the south Sirius will be shining at its highest, with the other bright stars of Canis Major to its right and below it.

Sirius is the bottom star of the bright, equilateral Winter Triangle. The others are Betelgeuse in Orion's shoulder to Sirius's upper right, and Procyon the same distance to Sirius's upper left. The Triangle now stands upright on Sirius, just about in balance.

And look west of the zenith for Perseus now heading down. If you're in the Mountain or Pacific time zones, you'll see that Algol, the prototype eclipsing variable star, is near its minimum brightness of magnitude 3.4 instead of its usual 2.1. Algol takes several additional hours to fade and to rebrighten. Use our comparison-star chart to judge its brightness all through the night.

MONDAY, JANUARY 1

■ If your sky is reasonably dark, trace out the winter Milky Way arching across the sky. In early evening it extends up from the west-northwest horizon along the vertical Northern Cross of Cygnus, up and over to the right past dim Cepheus and through Cassiopeia high in the north, then to the right and lower right through Perseus and Auriga, down between the feet of Gemini and Orion's Club, and on down toward the east-southeast horizon between Procyon and Sirius.

TUESDAY, JANUARY 2

■ After dinnertime now, the enormous Andromeda-Pegasus complex runs from near the zenith down toward the western horizon. Just west of the zenith, spot Andromeda's high foot: 2nd-magnitude Gamma Andromedae (Almach), slightly orange. Andromeda is standing on her head. About halfway down from the zenith to the west horizon is the Great Square of Pegasus, balancing on one corner. From its bottom corner run the stars outlining Pegasus's neck and head, ending at his nose: 2nd-magnitude Enif, due west and also slightly orange.

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 3

■ Last-quarter Moon tonight (exact at 10:30 p.m.). The Moon, in Virgo, rises around midnight or so. As the hours advance into the morning of Thursday the 4th, Spica comes up to twinkle less than a fist under the Moon as shown below. They're higher by the beginning of dawn.

■ The Quadrantid meteor shower should peak during these same early-morning hours of Thursday, moonlight and all. The Quads are often considered elusive because the shower's main part lasts only about six hours. But this year, those hours should be centered on about 4 a.m. EST. That's in the good pre-dawn Quad-watching hours for North Americans, especially easterners.

The shower's radiant is in the obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis in northern Boötes, climbing the northeastern sky during that time. Position your meteor-watching lawn chair to keep the glary Moon out of your eyes, and watch whatever part of your sky is darkest. Be patient. The number of Quads you may see per hour is fairly unpredictable.

THURSDAY, JANUARY 4

■ Orion strides upward in the east-southeast after dinnertime. Above it shines orange Aldebaran, 1st magnitude, with the large, loose Hyades cluster in its background. Binoculars are the ideal instrument for this cluster given its large size: its brightest stars (4th and 5th magnitude) span an area about 4° wide. Higher above, the showier Pleiades are hardly more than 1° across if you count just the brightest stars.

The main Hyades stars famously form a V. It's currently lying on its side. Aldebaran forms the lower tip of the V.

With binoculars, follow the lower branch of the V to the right from Aldebaran. The first thing you come to is the House asterism: a pattern of stars like a child's drawing of a house with a peaked roof. The house is currently upright and bent to the right like it got pushed.

The House includes three easy binocular double stars that form an equilateral triangle, with each pair facing the others. The brightest pair is Theta1 and Theta2 Tauri. You may find that you can resolve the Theta pair with your unaided eyes.

FRIDAY, JANUARY 5

■ At this coldest time of the year, Sirius rises around the end of twilight. Orion's three-star Belt points down almost to its rising place; watch there. Once Sirius is up, it twinkles slowly and deeply through the thick layers of low atmosphere, then faster and more shallowly as it gains altitude. Its flashes of color also moderate and blend into shimmering whiteness as it climbs to shine through thinner air. See Steve O'Meara's "Scintillating Sirius" in the January Sky & Telescope, page 45, with a photo of its scrambled-rainbow appearance as reflected on water.

To help find your way in a light-polluted sky, the blue 10° scale is about the width of your fist at arm's length. Jupiter, Hamal (Alpha Arietis), and Alpha Trianguli are stacked nearly vertically about that far apart.

SATURDAY, JANUARY 6

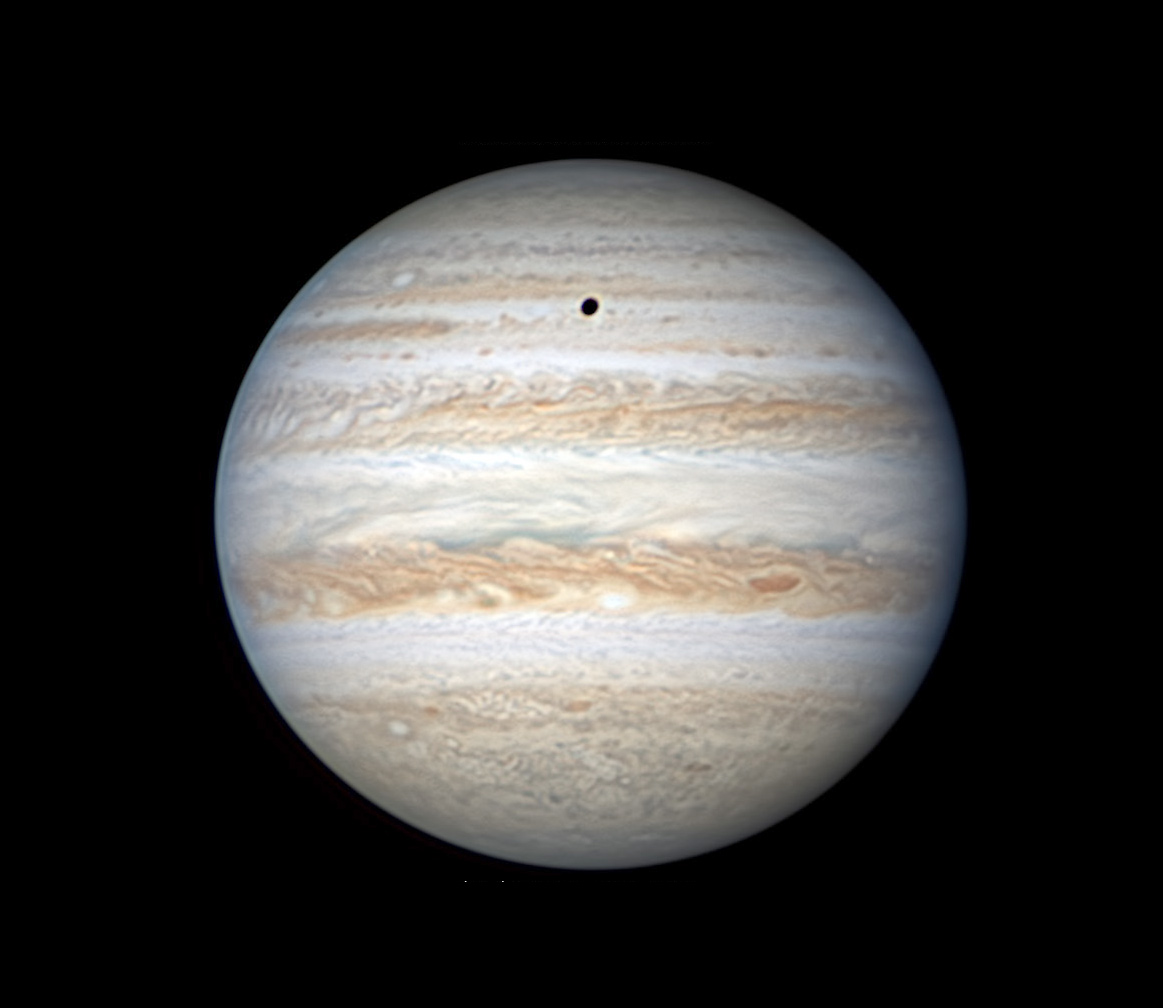

■ It's a busy evening among Jupiter's moons with four pairs of events. And they include a double shadow transit!

– At 5:47 p.m. EST, Io disappears into occultation behind Jupiter's western edge. Just 9 minutes later, Ganymede emerges from in front of the same edge. These two events will only be visible from the Eastern and Atlantic time zones, and the sky there may still be bright with twilight (depending on where you are).

– At 8:27 p.m. EST, Europa exits Jupiter's west limb. Nine minutes later Europa's tiny black shadow, trailing behind, comes onto Jupiter's opposite limb.

– At 10:13 p.m. EST, Io emerges from eclipse by Jupiter's shadow a small distance off the planet's east edge. Seven minutes later Ganymede's shadow crosses onto Jupiter's opposite edge, thus beginning a 35-minute period of two shadows in transit at once.

– At 10:55 p.m. EST, Europa's shadow leaves the western limb. Just over an hour later, at 11:58 p.m., Ganymede's larger shadow does the same.

And on Jupiter itself, the Great Red Spot (neither very great nor particularly red these days) should cross the planet's central meridian around 11:05 p.m. EST.

SUNDAY, JANUARY 7

These moonless evenings are a fine time to explore telescopic sights in Eridanus west of Orion — including the sky's least-difficult telescopic white dwarf star, many interesting doubles, and a fine, globular planetary nebula. For your guide use Ken Hewitt-White's "Suburban Stargazer" column, with finder chart, in the January Sky & Telescope starting on page 55.

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury shines low in the dawn this week to the lower left of bright Venus. Their separation shrinks from 22° on the morning of December 30th to 14° on January 6th. During this time Mercury brightens rapidly by 2½ times, from magnitude +1.0 to 0.0.

Venus, magnitude –4.0 in Libra, shines as the bright "Morning Star" in the southeast before and during dawn. It's getting a little lower every week. Below or lower right of Venus is sparkly orange Antares, magnitude +1.0. Their separation closes from 11° to 6° this week.

Mars barely peeks over the eastern horizon in bright dawn, probably out of reach even with binoculars or a telescope. Mars will very slowly creep up for the next five months.

Jupiter, magnitude –2.6 in Aries, is the bright white dot dominating the high southeast to south these evenings. It stands at its highest around 7 or 8 p.m. It has shrunk since opposition but still appears 44 or 43 arcseconds wide in a telescope.

Saturn, magnitude +0.9 in Aquarius, is getting lower in the southwest during and after dusk. Don't confuse it with Fomalhaut, similarly bright, nearly two fists to Saturn's lower left as shown below. Saturn sets around 8 or 9 p.m.

Uranus, magnitude 5.6 in Aries, awaits your binoculars in the darkness 14° east (left) of Jupiter. In a telescope at high power Uranus is a tiny but distinctly nonstellar ball, 3.8 arcseconds in diameter. Locate and identify it using the finder charts in the November Sky & Telescope, pages 48-49.

Neptune, fainter at magnitude 7.9, is at the Aquarius-Pisces border 21° east of Saturn and is still fairly high in the early-evening dark. Neptune is only 2.3 arcseconds wide: harder to resolve as a ball than Uranus, but definitely nonstellar at high power in good seeing.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows all stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. The next up, once you know your way around, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to mag 9.75). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham's Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer's Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don't think, especially not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning the sky. And as Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

But finding a faint telescopic object the old-fashioned way with charts isn't simple either. Learn the tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty's monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It's free.

"The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It's not that there's something new in our way of thinking, it's that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before."

— Carl Sagan, 1996

"Facts are stubborn things."

— John Adams, 1770

2

2

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

December 30, 2023 at 11:58 pm

I think there's an error in the note for Saturday January 6.

"– At 10:55 p.m. EST, Io's shadow leaves the western limb."

should be "Europa's shadow".

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

January 2, 2024 at 10:50 am

I did some solar viewing this morning, Perihelion Day 🙂 Observed 0930-1015 EST. Perihelion Day today. Skygazer's Almanac 2024 shows today is perihelion day at 1939 EST. Stellarium 23.4 shows the Earth is about 0.983 au distance from the Sun. Spaceweather.com reports on AR3536, AR3534, and AR3531 active regions today. "Sunspot AR3536 has a 'delta-class' magnetic field that poses a continued threat for strong X-class solar flares. Credit: SDO/HMI...BRACE FOR IMPACT: A CME is expected to graze Earth's magnetic field today, Jan. 2nd. Normally, grazing impacts have little effect, but this one might be different. The CME was hurled into space by the strongest solar flare of Solar Cycle 25, an X5-class explosion on New Year's Eve. G1-class geomagnetic storms are likely when the CME arrives. CME impact alerts: SMS Text" I viewed the Sun using my glass white light solar filter and TeleVue 40-mm plossl for 25x. Cumulus clouds rolled in from NNW this morning and caused difficult seeing conditions, but I did get brief views of AR3536, much plage around the region visible, AR3534 small dark core, and AR3531 with plage areas. Skies partly cloudy, temperature 4C, winds 320/12 knots. Earth size on the Sun is about 17.9 arcseconds, SOHO shows AR3536 region about 10 earth diameters or larger but smaller dark cores though, https://soho.nascom.nasa.gov/data/synoptic/sunspots_earth/mdi_sunspots_1024.jpg. At 25x, telescope resolution is about 12 arcsecond, about 8555 km diameter on the Sun. The passing cumulus bands made it difficult viewing this morning but between breaks in the clouds, I could see the Sun more distinctly.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.