When the Moon’s shadow swept across Earth on April 20th, tens of thousands traveled to Australia, Timor-Leste, and Indonesia to witness the celestial spectacle.

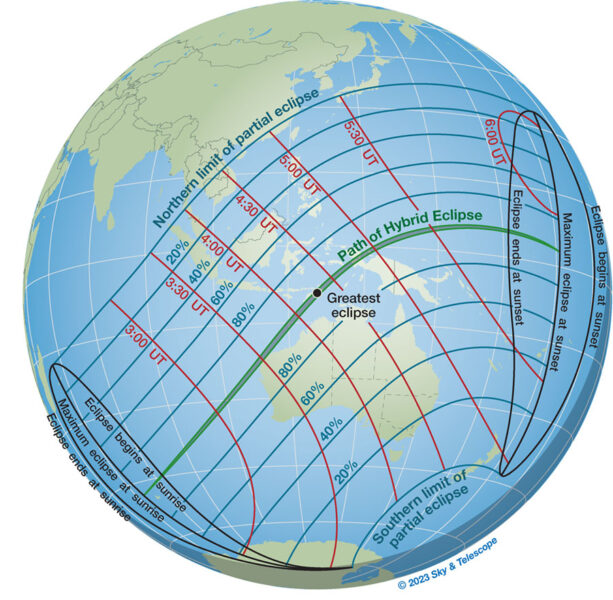

More often than not, eclipse-chasers have a challenging time getting to the path of a total solar eclipse, and that was certainly true for anyone who wanted to see April 20th’s event. The path of totality crossed very little land — it started in the southern Indian Ocean, barely clipped the westernmost corner of Australia, and crossed Timor-Leste and eastern Indonesia before sliding off into the Pacific Ocean.

Sky & Telescope / Fred Espenak

However, such remoteness didn’t deter thousands of “umbraphiles” who crammed onto Australia’s remote Exmouth Peninsula or aboard cruise ships off the Australian coast. Eclipse day dawned nearly cloud free all along the track, even though a powerful cyclone had battered the region just a week beforehand.

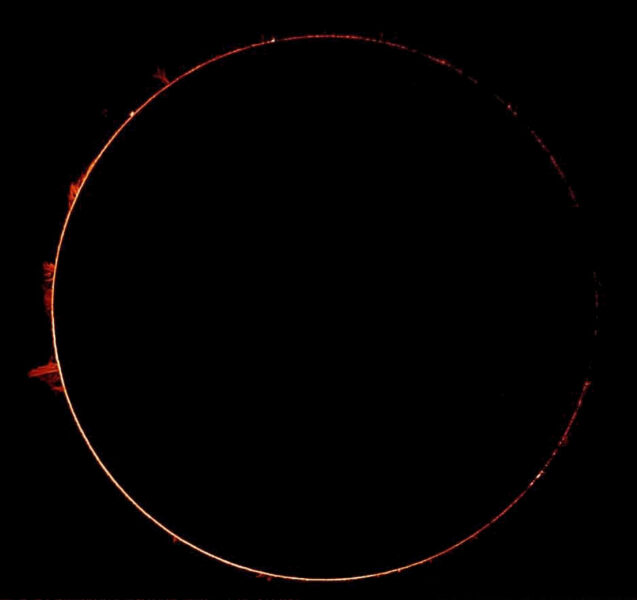

The event was a geometric oddity: a hybrid solar eclipse, one that is total in the middle but annular at its beginning and end. This occurs because the Moon appears slightly larger at the mid-eclipse point than it does at the beginning and end of the eclipse track, which are one Earth radius farther from the Moon. So the Sun’s disk is completely covered from that midpoint but appears as a thin or broken ring at either end of it.

Patrick Potevin

Above is an example of what that looks like, as seen by an observer on the tiny island of Kusrae, a tiny island in Micronesia some 3,800 miles to the northeast of Exmouth and very near the limit of totality’s visibility. This unusual geometry, which occurs roughly once per decade, meant that totality on April 20th would be brief — a meager 1m 16s at the point of greatest eclipse (near Timor-Leste).

Still, the event was a big draw: Some 15,500 visitors surged into the area in and around Exmouth, ordinarily a quiet town of roughly 3,000, and thousands more packed cruise ships off the coast. Sky & Telescope’s group of 140 enjoyed totality while anchored in Exmouth Gulf aboard P&O Cruises’ 2,000-passenger Pacific Explorer, and I traveled literally halfway around the world (Boston to Perth) to join them.

Pat Espenak

Timor-Leste was another popular destination for eclipse-chasers. Bob Kieckhefer observed from near Com, on the island nation’s eastern tip. “We had a few small clouds in the area, but they were well away from the Sun during totality,” he reports. “We saw great shadow bands both before and after totality.”

Special Effects

Given the near-perfect match of the solar and lunar disks in the sky, this eclipse offered some interesting phenomena that are not commonly seen during total solar eclipses. For example, Baily’s beads (the bits of Sun still in view along the Moon’s crenulated limb just before and after totality) were especially dramatic. Long swaths of the brilliant, crimson chromosphere rimmed the merged disks, punctuated by large prominences on the leading edge. The largest of these jutted 50,000 miles (six Earth diameters) high.

Right: Taken from a tiny strip of beach on uninhabited Ah Chong island in the Timor Sea, this view through a Nikkor 400-mm lens and 1.4× teleconverter captures the dramatic prominences on display during the total solar eclipse on April 20, 2023. Eliot Herman

Of course, the feathery solar corona was the big draw, and it did not disappoint. Several bright streamers fanned out all around the disk — the kind of well-spaced arrangement that’s characteristic of the corona’s appearance near solar maximum. (During solar minimum, the streamers are usually concentrated at the Sun’s equatorial latitudes.)

Joo Beng Koh

Anyone who’s seen totality will tell you that photos just can’t fully capture what the human eye sees. I asked Fred Espenak, one of the great masters of solar-eclipse imaging, to render this eclipse as it might have been seen by someone watching through binoculars — and then create a second version to maximize all of the tortured magnetically-driven detail present in the corona. Here’s the result:

Fred Espenak

“No photo has the dynamic range to reproduce the range of brightness see with the naked eye,” Espenak says. “The prominences are particularly hard to to capture in such a ‘naked-eye’ composite. They really should be much brighter than shown, but this would completely wash out their color.”

Meanwhile, because totality’s path was less than 30 miles (50 km) wide, the sky never got very dark at mid-eclipse — though Jupiter (just 6° away) and Venus were easily seen.

All Eyes on the Americas

This was the first total solar eclipse since December 21, 2021, an equally challenging event observable only from Antarctica or the Southern Ocean. But now diehard eclipse-chasers will get a reprieve. Next up is an annular (ring) solar eclipse on October 14th that crosses the western U.S., the Yucatán, Central America, and northern South America.

Six months later, on April 8, 2024, the Moon’s shadow races over central Mexico before heading across much of the U.S. and the Canadian Maritimes. It’ll be the second such event for Americans in a span of seven years, and this time totality will last up to a generous 4½ minutes. Check out Sky & Telescope’s extensive resources for maximizing your view of next April’s highly anticipated event.

| Got eclipse fever? Be sure to check out the exciting Sky & Telescope eclipse expeditions planned for the Yucatán Peninsula (October 2023), a “Mexican Riviera” cruise (April 2024), Easter Island (October 2024), and beyond. |

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.