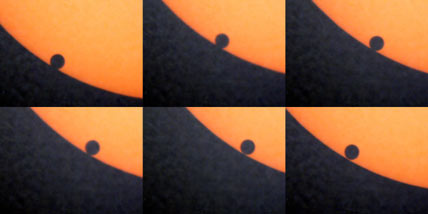

This series of images shot from Singapore shows a distinct black-drop effect. But most higher-quality images showed none at all.

Courtesy Joseph Tey .

As reports on the Venus transit come in from around the world, the burning question in the observational community surrounds the "black drop": Why did some people see it while others did not? Did it happen at all?

The black-drop effect is seen when a dark patch appears to connect Venus with the dark sky past the edge of the Sun, sometimes giving Venus a teardrop shape. It was widely observed and commented on in the 18th and 19th centuries. Yet most observers didn't report seeing a black drop this time. Of those who did, most saw something much less pronounced than the effect observed in the past — so much less pronounced that they hesitated to call it a black drop at all.

Opinions range as to why there is a discrepancy. The leading theory cites today's better telescope quality. Unusually good atmospheric seeing has also been suggested.

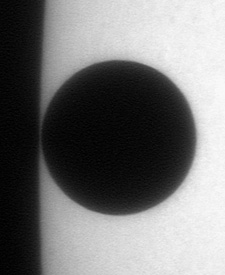

Three webcam images were combined to reveal the moment of second contact. This image was taken through the 16-inch f/16 refractor at the Vatican Observatory at the Pope's summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, Italy.

Sky & Telescope photograph by Dennis di Cicco.

Lorenzo Comolli watched the transit from outside Milan, Italy, with an 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain and reported seeing the black drop at egress but not at ingress. At ingress, he said, "Because the seeing was quite good, I've not seen the black drop. The entrance of the disk was very sharp." At egress, under worse seeing conditions, "the black drop was evident, especially in the worst seeing moments."

S&T contributing editor Govert Schilling, who watched the transit from Utrecht, The Netherlands, remarks: "When looking at ingress with a pair of binoculars, I thought I could see something that you might call a black drop effect, but looking through larger instruments (of the Sonnenborgh Observatory), nothing like a black drop was seen."

Some pictures of the transit show contact points with no hint of black drop whatsoever (see image above). Others show a slightly darker, fuzzy patch between Venus and the edge of the Sun at ingress or egress that does not actually distort the planet's apparent disk. Few show the pronounced teardrop shape in reports from past centuries.

"Some of it may be a matter of degree," says Jay Pasachoff (Williams College). He says his study with Glenn Schneider (University of Arizona) of space-based images of the 1999 and 2003 Mercury transits shows that the telescope's optics and resolving power are a factor in the black-drop effect. "So it's not a surprise that big telescopes that have a better point-spread function don't show a black drop effect." Pasachoff will be studying images from the Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE) satellite to try to better understand the effect.

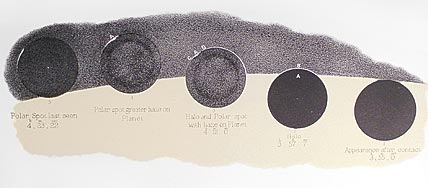

Venus's egress in 1874, drawn by Henry Chamberlain Russell with an 11½-inch refractor. The right-hand view shows the black drop just after third contact, while the others show (from right to left) the development of the ring of light. Due to Russell's use of a diagonal prism, this figure is mirror-reversed.

Courtesy John Westfall.

So the "black-drop effect" remains as enigmatic in the 21st century as in the 19th. Debate is likely to continue over what constitutes a "true" black drop as more observations pour in. And it remains to be seen whether the conditions for the appearance of black drop will be nailed down as observers compare notes over the coming weeks and months, or even in time for the next transit on June 5-6, 2012.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.