New Horizons has spotted two asteroid pairs in the outer solar system. Their existence sheds light on how planets formed.

NASA / JHAPL / SwRI

NASA’s New Horizons is still showing us how bizarre the outer solar system really is. A recent announcement out of the 53rd American Astronomical Society Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences demonstrates that two Kuiper Belt objects that the spacecraft's camera homed in on are actually each close binary pairs.

#PI_Daily The news is out: @NewHorizons2015 has discovered the tightest orbit binary Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) ever! This was accounted by Dr Hal Weaver in a presser today, see: https://t.co/CNzdH1tIf9 We can only do this because we pass KBOs closely as we transect the belt! pic.twitter.com/lyD0x99cl2

— Alan Stern (@AlanStern) October 6, 2021

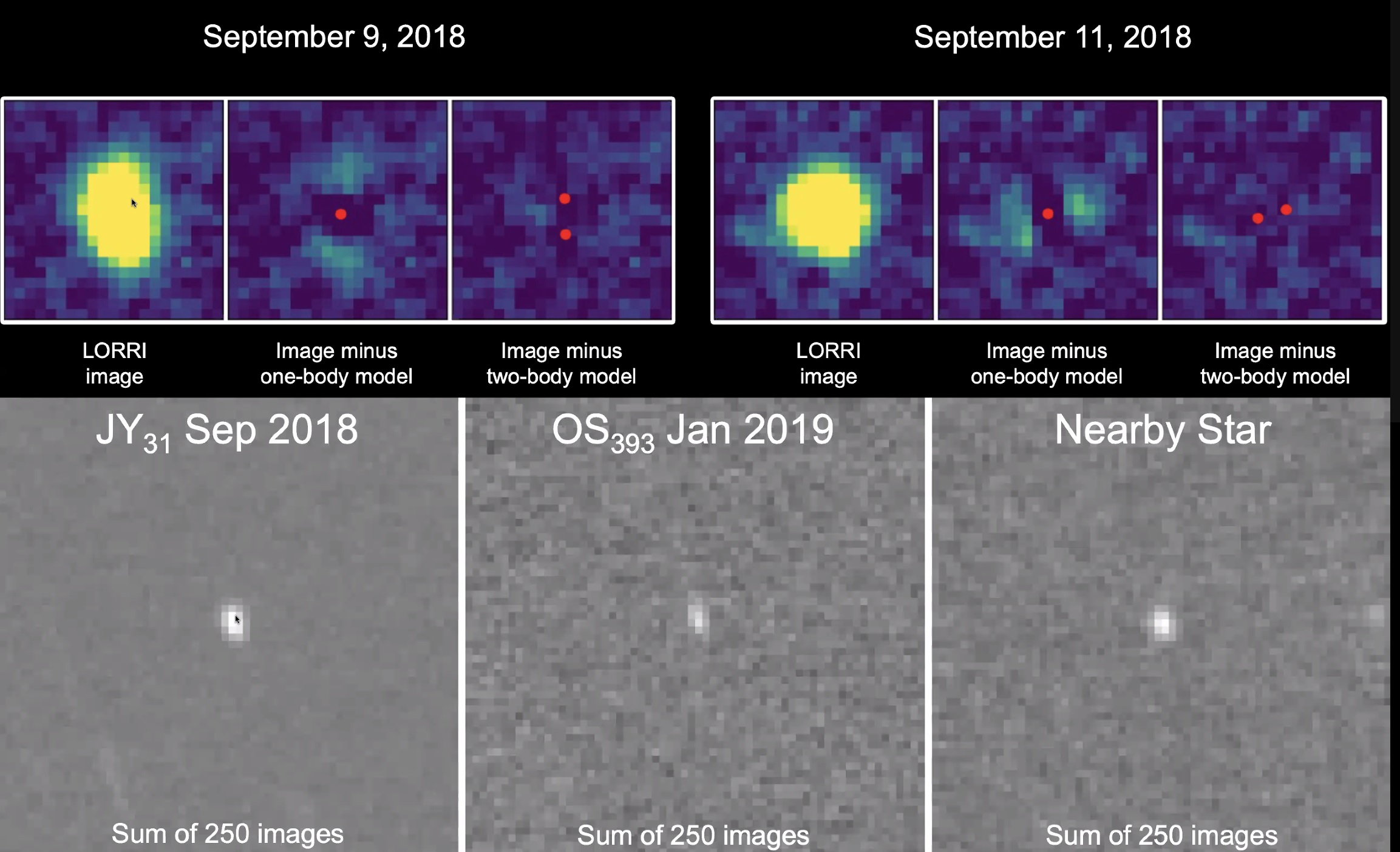

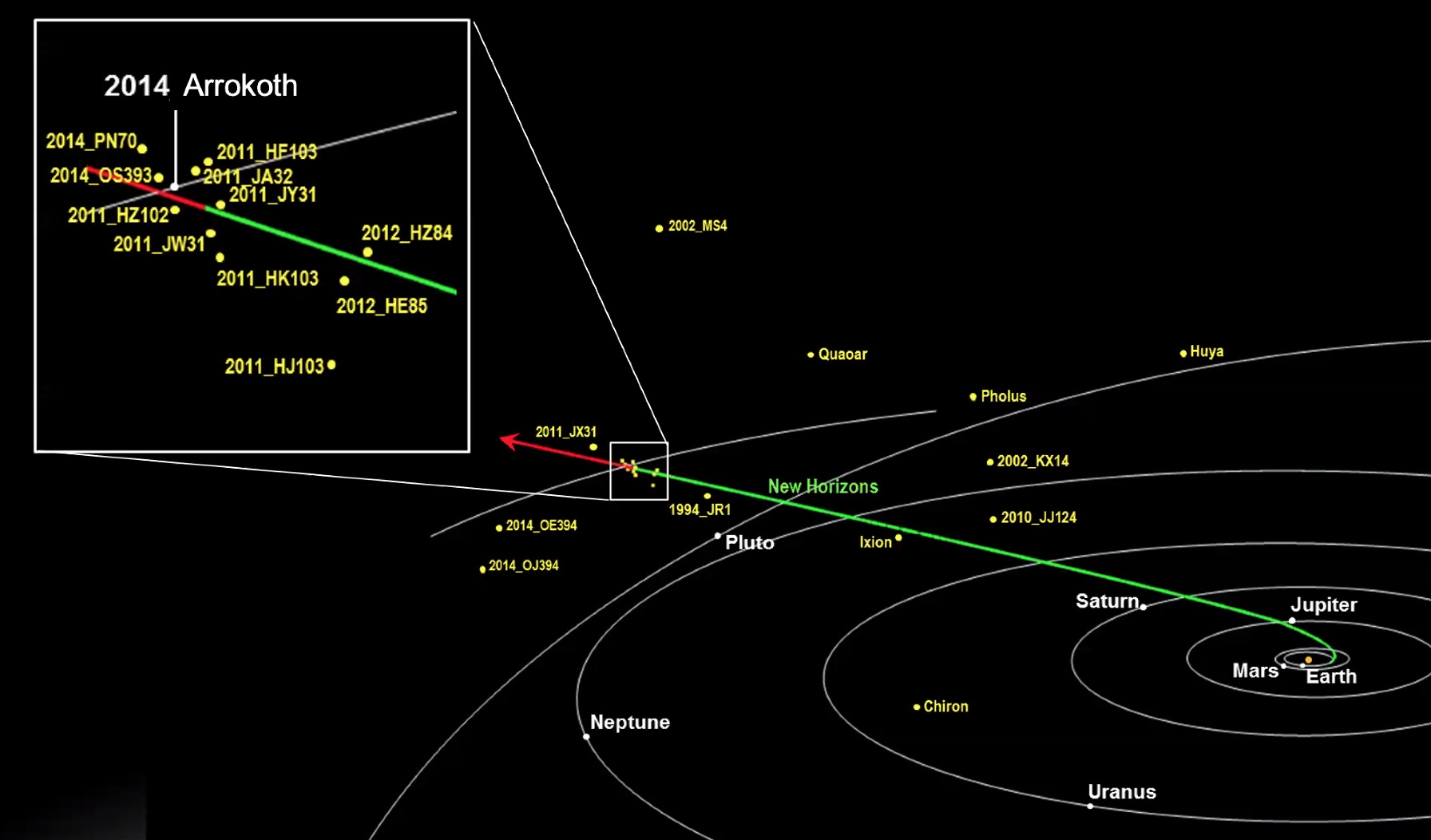

The binary asteroids are named 2011 JY31 and 2014 OS393. Ground-based observatories discovered these objects, then New Horizons’ Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) camera captured the former in September 2018, after its Pluto flyby while it was still en route to Arrokoth. The spacecraft imaged 2014 OS393 just after its Arrokoth flyby in January 2019.

NASA / JHAPL / SwRI

The high-resolution LORRI imager is equivalent to an 8-inch reflector telescope, familiar to many amateur astronomers. To be considered for the study, the objects, when they were targeted, had to lay within 0.3 astronomical units of the path of New Horizons (where 1 a.u. is the average distance between Earth and the Sun): 2011 JY31 was 0.15 a.u. distant, and 2014 OS393 was just 0.09 a.u. away.

Both 2011 JY31 and 2014 OS393 appeared slightly elongated in the images compared to a nearby star. So the team fit the shapes with a two-body model: two asteroids in a tight orbit. Even though the individual rocks weren't resolved, the modeling showed that two bodies were better able to explain the elongation, as well as the brightness seen. The model for 2011 JY31 had two 50-km-wide objects nearly 200 km apart, while for 2014 OS393, the model had slightly smaller bodies (30 km across) that orbited each other 150 km apart.

NASA / JHAPL / SwRI

New Horizons examined three objects of the “cold classical” family of the Kuiper Belt, says Hal Weaver (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory). This family is especially primitive, having formed early on in the solar system's history and not changed much since then. “One of them, we could only get it into the little window for half the time,” Weaver says. “For the other two, we do see evidence that they’re binary.”

New Horizons examine one other object that's a member of the "scattered disk" family, Kuiper Belt objects that underwent some interaction that changed their original orbit. That one doesn't appear to be binary, Weaver says.

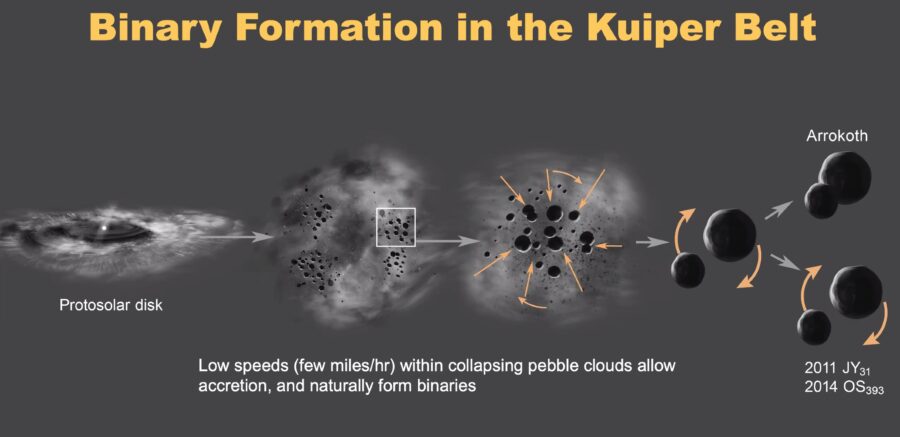

The tight-orbiting twins would have formed in situ, and — like twin-lobed Arrokoth seen up close by New Horizons in early 2019 — support a formation model in which gentle, low-velocity collisions among small objects, or “pebbles,” produce denser pebble-filled clouds that then collapse into larger planetesimals, as either contact binaries (like Arrokoth) or tight twins (like the other two asteroids).

Even a small close-up census of Kuiper Belt objects gives us important insight into how protoplanetary formation occurred in the early solar system.

NASA / JHAPL / SwRI

Launched from Cape Canaveral on January 19, 2006, New Horizons visited Pluto in 2015, then went on to fly 2,200 miles past Arrokoth on New Year’s Day 2019. Since then the team has been keeping busy, completing the longest parallax baseline measurement in 2020 and making measurements of background visible light coming from the cosmos.

NASA / JHAPL / SwRI

It turns out that we got to the Pluto-Charon system just in time, as another study out at the Division for Planetary Sciences conference this week confirms that Pluto’s nitrogen atmosphere is freezing out, as expected as the tiny world is heading toward aphelion in 2114. The study used the occultation of a 13th-magnitude background star to examine Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere, along with comparison observations from New Horizons post-flyby.

NASA / JHAPL / SwRI.

A third flyby target for New Horizons is not out of the question, as the spacecraft has enough remaining fuel for additional course corrections. But space is big and these objects are far and few between. The hunt is further complicated by New Horizons position on the sky. The spacecraft is now 51 a.u. away in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius, a star-rich region along the galactic plane.

“It’s a long-shot,” Weaver says, “but this is humanity’s only mission to the Kuiper Belt for the next couple decades, so we're trying to squeeze every last bit we can out of it.”

Large ground-based telescopes are aiding the search for additional targets. And there’s a good chance that the next generation of telescopes coming online in the next year, including the James Webb Space Telescope and the Vera Rubin Obesrvatory, could turn up a suitable target.

Expect more amazing science to come from New Horizons, as it explores the outer solar system. Are all the objects out there this weird?

4

4

Comments

Pierre-Paquette

October 8, 2021 at 5:30 pm

I’m not sure I understand this line, care to explain it, please?

“The objects, when they were targeted, lay 0.3 astronomical units away (where 1 a.u. is the average distance between Earth and the Sun): 2011 JY31 was 0.15 a.u. distant, and 2014 OS393 was just 0.09 a.u. away.” So, were they 0.3, 0.15, or 0.09 au away?

Also, a few lines lower, it says “as well as t. The…” I think the sentence is broken.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica Young

October 12, 2021 at 9:21 am

This typo was fixed in the text, thanks for pointing it out.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

October 12, 2021 at 8:47 am

The report states here, "Launched from Cape Canaveral on January 19, 2006, New Horizons visited Pluto in 2015, then went on to fly 2,200 miles past Arrokoth on New Year’s Day 2019. Since then the team has been keeping busy, completing the longest parallax baseline measurement in 2020 and making measurements of background visible light coming from the cosmos."

It should be interesting reading when the stellar parallaxes are published for this project. I noted in my astronomy spreadsheet concerning calculating stellar parallax: [New Horizons long-baseline parallax compared to stellar parallax using Earth orbit distance around the Sun is about 2 AU baseline. New Horizons baseline at 47 AU will show parallax 47/2 = 23.5x larger in arcsecond than parallax from Earth's orbit. 61 Cygni star is 314 mas stellar parallax, first measured in 1838. That is 0".314 parallax. 61 Cygni parallax at baseline of 47 AU is 7".379 or 0.314 x 23.5 larger angular size. Results published should be very interest.]

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mathieudelyon

October 12, 2021 at 10:50 am

Amazing !

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.