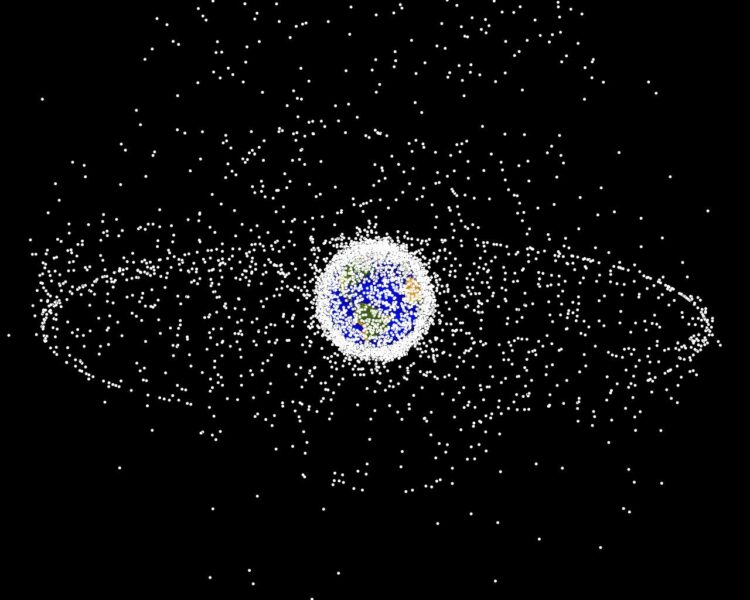

New observations show we’re not tracking a majority of debris in higher orbits.

NASA / JSC

The problem of space debris is complex and sobering. Since the launch of Sputnik 1 in early October 1957, the population of objects actively tracked and cataloged in Earth orbit has increased to more than 20,700 satellites and fragments, from debris in low-Earth orbit (LEO) to satellites in geosynchronous and geostationary (GEO) orbits 22,236 miles (35,786 kilometers) from the Earth.

But that's only a small fraction of the estimated 1 million fragments out there that are larger than 1 centimeter in size. A new study out of the University of Warwick confirms that the GEO population in particular isn't well understood — most of the objects identified in the study failed to match up with bodies in known space debris catalogs.

DebrisWatch

The study was part of a project known as DebrisWatch I, a collaboration between the University of WarwickUK's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory. The study employed two telescopes at La Palma in the Canary Islands, Spain, to find and track GEO debris: the 2.54-meter Isaac Newton Telescope and a 0.36-meter astrograph located at the same site.

Though the expanse of GEO is large, it’s also confined to the equatorial region. (In fact, some regions of the sky, such as the one containing the Great Orion Nebula (Messier 42), are notorious for GEO satellites photobombing astrophotos at certain times of year.)

To track satellites and debris in GEO, researchers simply turned off equatorial tracking, letting stars trail through the field of view while objects in GEO remain as pinpoint dots. They could see objects in GEO down to an integrated visual magnitude of +21.

“At GEO, objects are moving with a relatively predictable rate,” says Don Pollacco (University of Warwick). “The main confusion is with HEO/MEO [high/medium Earth-orbit] satellites, but even these are relatively easy to remove.”

The astronomers tracked objects down to 10 centimeters across, finding that 75% of their detections failed to match known objects in the U.S. Strategic Command’s Space-Track catalog. The brightness of many objects changed over time, a telltale sign that an object is tumbling in orbit.

University of Warwick

A Mounting Problem

Debris in GEO accumulates over time, resulting from shedding or collision. Many old boosters used to place satellites in orbit simply break up over time. And unlike LEO, satellites in GEO are too far away to come back to Earth and burn up in its atmosphere.

“A number of recent breakups acted to motivate our search for faint (likely small) debris at these altitudes,” says James Blake (University of Warwick). “Recent simulations have found that relative velocities can still be of the order of a kilometer every second in GEO, so even small fragments can cause a lot of damage to active satellites.”

Science fiction writer and futurist Arthur C. Clarke first realized the utility of placing a satellite in GEO: orbiting Earth every 24 hours, it would keep pace with the same longitude of the planet below. As of March 31, 2020, 554 satellites have been placed in GEO, their purposes ranging from weather and communications to spying.

James Blake / University of Warwick

The Future of GEO Space Debris

U.S. Strategic Command tracks a majority of the debris in LEO via its globe-spanning Space Surveillance Network (SSN), which uses 6 satellites and 30 ground tracking stations to monitor the situation. Human-made debris still up there dates all the way back to Vanguard 1, launched on March 17, 1958.

But it’s tougher to follow debris in higher orbits, as it requires employing powerful radar over a much bigger volume of space. Although such systems do exist, optical tracking is the preferred method to track distant satellites in GEO. The SSN can only track objects in GEO down to about 1 meter across.

The methods and algorithms developed in the new study will go a long ways towards improving future tracking of small, distant debris — especially as new facilities come online.

One site located on Ascension Island in the South Atlantic currently uses a 1.3-meter telescope for debris tracking. Recently, researchers at the Institute of Space Research in Austria also demonstrated the unique capability of tracking space debris in the daytime.

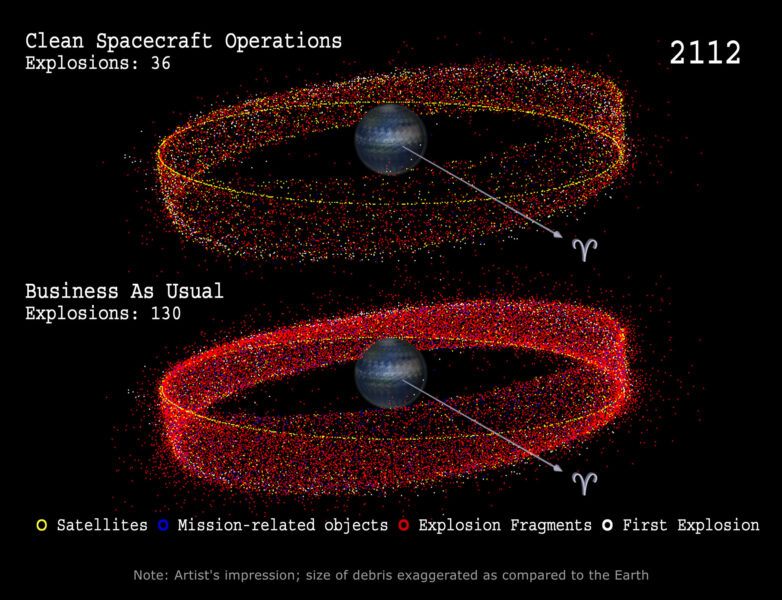

ESA

“These (GEO) orbits are usually assumed to be low in debris, but over the past few years there have been a number of spacecraft that have broken apart or apparently exploded,” says Pollacco. “While it’s not confirmed that these events were caused through debris, what is clear is that there is now a debris field moving in GEO.”

The video below shows such a debris incident:

Options for cleaning up GEO are limited, though. Most modern GEO satellites are simply moved to higher "graveyard" orbits at the end of their careers.

A worst-case scenario is a collisional cascade where one collision begets two more, and so on. Known as the Kessler syndrome and famously depicted in the science fiction movie Gravity, it's more relevant right now for the packed LEO environment, but it could eventually become a problem for GEO, too.

10

10

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

October 8, 2020 at 4:42 pm

The video is dramatic. Was the satellite still working? Or was it was just a big piece of junk suddenly becoming lots of little pieces of junk?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

October 9, 2020 at 7:30 am

Contact was lost with Telkom-1 after the incident: https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/telkom-1.htm

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 9, 2020 at 4:44 pm

Thanks for the info and the link. It sounds like this was a working satellite providing telecommunications for a developing country. Do we know if the satellite was destroyed by an impact with space junk. or did it just blew up on its own?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh77

October 9, 2020 at 4:58 am

You made an error.

Human-made debris up there dates all the way back to Sputnik 1, launched on October 4, 1957 by the USSR.

Not Vanguard 1.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

October 9, 2020 at 7:27 am

While Sputnik 1 was launched earlier, it also re-entered on January 4th, 1958. Vanguard-1 is still in orbit.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh77

October 9, 2020 at 7:54 am

Ok. I didn't know that there were no more pieces of Sputnik 1 left in Space.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

DAVID

October 9, 2020 at 5:31 pm

I believe there was a satellite blown up by a missile from China or Korea a while back creating more space debris. Does anyone know if this occurred in the LEO or GEO orbit regions?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 9, 2020 at 10:48 pm

A quick search yielded the following 2013 fact sheet from the Secure World Foundation:

https://swfound.org/media/115643/china_asat_testing_fact_sheet_aug_2013.pdf

According to this fact sheet, the United States, the Soviet Union, and China all tested anti-satellite warfare systems. Each program resulted in significant orbital debris. The last test that caused significant debris was a 2007 Chinese LEO test. China has carried out several more recent non-impact tests, including one launch to GEO in 2013. I don't know what has happened since 2013.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Gg

October 11, 2020 at 11:35 am

Significant about the Soviet test was their use of a "shotgun" weapon that released a lot of pellets plus the large number of target fragments.

I think the US test had the orbits to result in a rapid decay of the debris.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John

October 13, 2020 at 4:41 pm

You neglected to mention the 12K Starlink satellites - talk about debris!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.