New measurements from the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite show that the young stars of the Hyades cluster are beginning to drift apart.

Bob King

Look up in the evening sky these days and you’ll see a striking V-shaped smattering of stars known as the Hyades — named for the daughters of Atlas and sisters of the more famous Pleiades. It’s the nearest known star cluster, 150 light-years from Earth, and contains a treasure trove of observing delights, as Bob King chronicled a couple weeks ago.

The stars of the Hyades are “only” several hundred million years old — youngsters in astronomical terms — so they shed light into our own star’s past. The Sun, too, was born in a cluster, surrounded by its stellar siblings. They all formed from the same cloud of dust and gas before time carried them apart. Now, measurements from the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite show how the Sun came to live in its current solitude: the stars of the Hyades, too, are beginning to go their separate ways.

Tidal Drift

That open clusters, which contain several hundred or maybe a thousand stars, should drift apart is a given. While massive clouds of dust and gas cocoon forming stars, those clouds dissipate once the stars start shining. After that, gravitational interactions easily disrupt the stars’ orbits. But until now it’s been a theorist’s game: we’ve only ever witnessed the prominent streams of stars pulled from more massive stellar gatherings, such as globular clusters or dwarf galaxies.

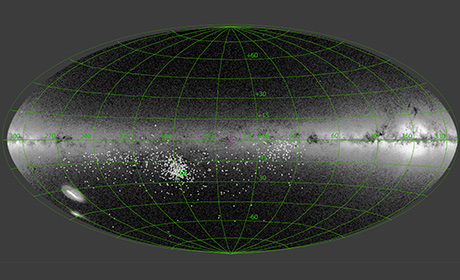

Now, though, observers have the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite, which has been mapping the positions, distances, and motions of billions of stars since 2013. Siegfried Röser (Heidelberg University, Germany) and colleagues used Gaia’s most recent data release to identify stars belonging to the Hyades. These include not only those stars located within the cluster itself, but also those fanning out in so-called tidal tails hundreds of light-years from the cluster center. One tail precedes the cluster in its orbit around the Milky Way; the other tail follows it.

S. Röser / ESA / Gaia / DPAC

Thanks to Gaia’s exquisitely precise data, the team could identify which stars were moving with the cluster as it orbits our galaxy, and which stars were moving just a bit faster or just a bit slower as the Milky Way’s gravity tugs them away from the center. In addition to 501 stars within Hyades itself, Röser identified 292 stars up to 550 light-years in front of the cluster and another 237 stars trailing behind by up to 230 light-years.

The study extends beyond the eventual dissolution of the Hyades. “Our discovery shows that it is possible to trace the trajectories of individual stars of the Milky Way back to their point of origin in a star cluster,” Röser explains.

Read more in the Heidelberg University’s press release and in the team’s paper appearing in the January issue of Astronomy & Astrophysics.

12

12

Comments

Peter Wilson

February 26, 2019 at 6:40 pm

Q. Why is the collective gravity of the Milky Way strong enough to eventually pull apart clusters like these, but not strong enough to disrupt the cloud of gas and dust that gave birth to the cluster?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

February 26, 2019 at 7:34 pm

WAG*. It only takes a couple hundred thousand years for a molecular cloud to collapse into the stars of a star cluster. During that time the protocluster won't rotate too far through the galaxy, so the galactic gravitational environment will be relatively stable. After formation the cluster will continue to rotate through the galaxy and will experience varying tidal pulls. As the cluster gets more spread out, any tidal forces will be amplified. Over hundreds of millions of years the forces of gravity and entropy will inexorably pull the cluster apart.

*Wild Ass Guess.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

February 27, 2019 at 11:08 am

That's certainly a factor. My DBG* is that when nuclear ignition kicks in, 90% of the original mass of gas/dust gets blown away by intense ultra-violet radiation. Thus, the new-born stars collectively retain only 1/10th of the original mass, dooming them to tidal disruption.

*Domestic Burro Guess

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

February 27, 2019 at 5:17 pm

That makes sense!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[email protected]

March 2, 2019 at 4:49 pm

PETER! you are so funny besides intelligent!!

I am glad they gave you an Observatory in LA entitled to your Name!!

love

marino

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Brent Studer

March 1, 2019 at 11:01 pm

It's not the collective gravity of the Milky Way, but the gravitational interactions of the stars in the open cluster that is the primary factor. Just as Zwicky used the virial theorem to deduce the presence of unseen mass in clusters of galaxies (the motion of the galaxies could not be explained by the gravitation due to visible mass alone), you can use the virial theorem to model the speeds and motion of stars as they interact in an open cluster. As the stars gravitationally interact with each other, the more stars in the cluster, the more likely the chance that any star's motion will be perturbed and it will be ejected from the cluster. Hence, open cluster evaporate over time as stars are ejected from the cluster and fewer stars are left to keep the cluster gravitationally bound.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica YoungPost Author

March 4, 2019 at 12:01 pm

It's both and more, I think - the stars in an open cluster are so loosely bound that it takes very little to tug one of their stars away, whether that's due to close stellar encounters within a cluster or an external star passing close by.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Gaylon-Arnold

February 27, 2019 at 1:14 am

50 years ago, in astronomy lab, I plotted the apparent motions of the stars in the Hyades Cluster. There was a definite outward trend on all the stars. Part of the apparent motion, it seemed at the time, was the approach of the cluster towards the Sun; indeed the Sun may pass through the cluster at some time in the future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

February 27, 2019 at 5:18 pm

How far into the future?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[email protected]

March 2, 2019 at 4:50 pm

good thinking!

will we feel the wind?

bless

mm

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ellenpa2000

March 2, 2019 at 7:00 pm

You guys are hilarious. But meanwhile I wonder if we know which stars are our sun's siblings from when they all were born together? I would love to know if we could still see them, or is the drift so enormous, we can't find them anymore?

Ellen, in Canada

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica YoungPost Author

March 4, 2019 at 11:58 am

Ellen, we definitely can find them, because we've found at least one! https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/sun-sibling-found/

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.