If you like mixing comets with the quietude of observing in the small hours, September opens with five fuzzy vagabonds just waiting for a visit.

Dan Bartlett

Sometimes I herd comets. Recently, the number of observable objects has grown, with four to five comets visible before dawn and another at nightfall. Despite the fact that none are what you'd call bright, there are too many to ignore. Ever since 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko hooked me on comet-watching back in 1982 I try not to let a single one of these celestial sliders slip by. Their movements, beautiful forms, and surprise outbursts and breakups make them irresistible.

Jean Francois Soulier

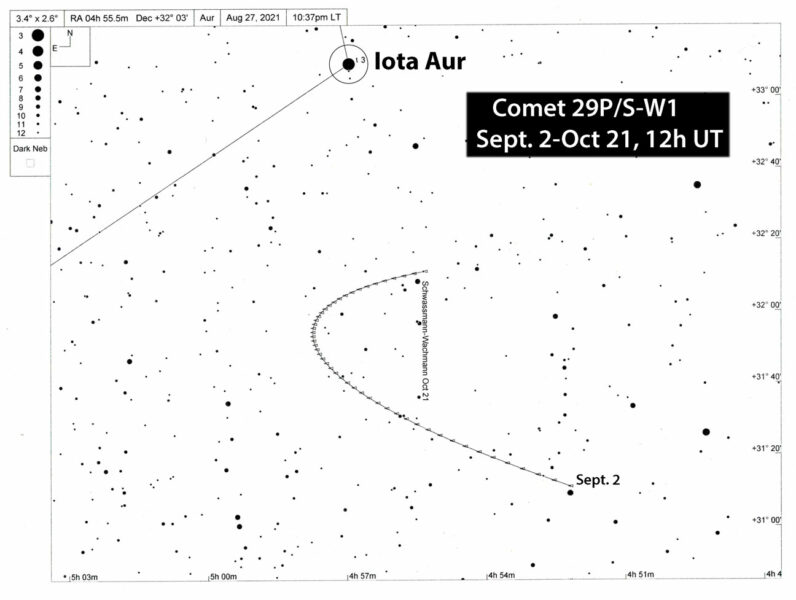

I've seen around 350 unique comets since my youth. Many of these are periodic, returning again and again at regular intervals. By far, 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann tops the list of most frequently observed. With an average distance of 6 a.u. it's ordinarily a 16th-magnitude smudge but undergoes multiple outbursts every year, when it can surge to easy visibility in an 8-inch.

MegaStar, used with permission

I mention it here because of its recent outburst in late August, when Comet 29P suddenly rose from magnitude 16 to 14. Keep an eye on this uneasy fella. Bright flare-ups that could kick the comet into view in a 6- to 8-inch telescope are inevitable. This season it's easy to keep track of because the comet remains within 2.5° of 2.7-magnitude Iota (ι) Aurigae now through mid-November. Most of the time you'll see nothing at its position, but then one night, a small knot of bright fuzz will alert you to a brand new eruption. If you'd like to participate in the ongoing observing campaign to study the nature and frequency of 29P's outbursts, click here.

** Update Sept. 5 — 29P underwent yet another outburst sometime around September 3-4 to ~12.5 magnitude, and is now fading.

Stellarium

Our other predawn comets include the aforementioned 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, ATLAS (C/2019 L3), 4P/Faye, and 15P/Finlay. Clicking the name will take you to individual high-resolution maps. Before wildfire smoke and moonlight put the kibosh on deep-sky observing here in northern Minnesota I got great views of all four on the mornings of August 13–14. For good measure, let's also include one evening comet in the mix — PanSTARRS (C/2017 K2).

Bob King

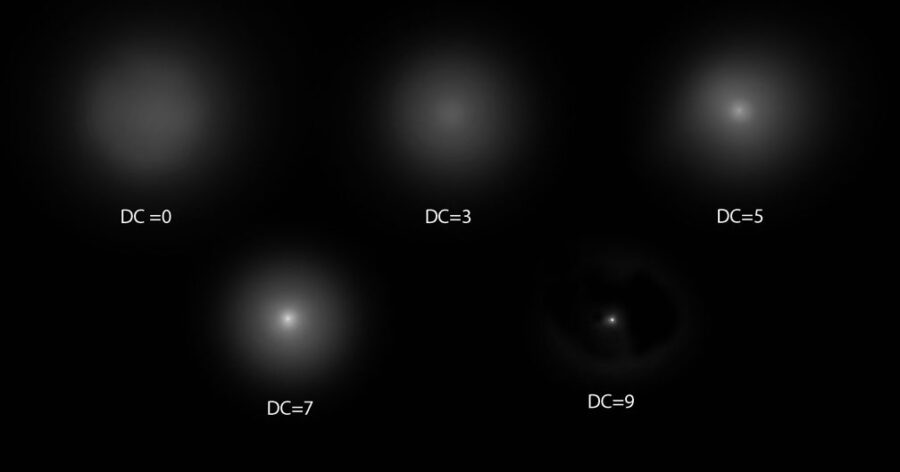

The easiest of the predawn gang is Comet ATLAS. It's small, very compact, and relatively bright at around magnitude 11.5. A comet's degree of condensation, or DC, plays a crucial factor in its visibility. Fainter comets with compressed cores are frequently much easier to see than large, diffuse objects with brighter apparent magnitudes.

Juanjo Gonzalez

Through my 15-inch Dob (used for all these observations) on August 13.4 UT I saw it as a tiny — just 45″ across — but bright and compact patch at magnitude 11.5 with a DC of 7. The comet will gradually swell to magnitude 10 in early 2022, making it a great fall and winter target. During September it slowly crosses from Lynx into Auriga, ideally placed in the northeastern sky before dawn.

What a joy to spot my old pal 67P again! In August it beckoned from Cetus, but it's now in Aries and will cross into Taurus on September 7th. Predictions suggest the comet currently glows at magnitude 12, but I estimated its brightness at 11.6 two weeks ago with a 1.5′-diameter, moderately compact coma (DC 5), and a dim 13.5-magnitude pseudo-nucleus.

Juanjo Gonzalez

"Chury" has brightened since then, so it may actually be closer to 11 at the moment. Take a look and let us know! Perihelion occurs on November 2nd with closest approach to Earth 10 days later. Expect the comet to peak at magnitude 9 around then as it tracks from Gemini into Cancer.

Periodic pair

I thought 4P/Faye and 15P/Finlay would be easy catches. Faye swam into view at magnitude 11.2 with a coma diameter of 2′, but because it wasn't as compressed (DC 4) as either ATLAS or 67P, it was less apparent. The comet should wax to magnitude 10 as it crosses from northern Orion into Gemini during the first half of October. Perihelion occurs on September 8th at 1.6 a.u., with closest approach to the Earth on December 6th (0.9 a.u.).

Comet 15P/Finlay took more effort yet, in part because of its low altitude at the time. At 142× I saw a 2′-wide smear of weakly condensed, 12th-magnitude haze (DC 2). Other observers estimated its brightness around magnitude 11 in mid-August. Although Finlay is now better placed as it crawls from Gemini into Cancer this month it will also slowly fade.

During its previous apparition in 2014–15 the comet experienced two bright outbursts that rocketed its magnitude to 9 in December 2014 and 8 in January 2015, so be on the lookout. Finlay next reaches perihelion in 2028 — catch it now or kiss it goodbye.

All four of these scope-worthy subjects stand highest in the sky just before the start of morning twilight. How fortuitous that dawn begins so much later than it did back in June. The moon will be out of the picture from September 3rd through the 19th, and the sky will be dark until around 5 a.m. local daylight time.

Juanjo Gonzalez

Evening catch

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention Comet PanSTARRS (C/2017 K2), which appears high in the southwestern sky in the Keystone of Hercules at nightfall. It inches south-southeast this month while gaining a couple tenths of a magnitude. On August 30.1 UT I easily spotted this dainty mini-marshmallow at magnitude 12 at 64×, my lowest magnification. Its moderately condensed (DC 5) coma measured 1′ across.

Comet PanSTARRS has a very long fuse — not until midsummer 2022 will it crest to a peak magnitude of 6 and shoot across Ophiuchus like a flitting firefly. You have through September 14 to view it before the Moon interferes with observation.

Resources:

Weekly Information about Bright Comets

Comet Observation Database

Comets Mailing List

Stellarium — free software to plot comet positions. Tutorial here.

15

15

Comments

John Bortle

September 2, 2021 at 6:50 pm

The illustration accompanying this article, supposedly depicting differing values of a comet's Degree of Condensation is, I'm afraid, largely inaccurate. It more reasonably depicts the appearance perhaps of varying intensities of a central condensation within the comet's coma (as per, possibly, the more complex Morris DC Scale, which judges the intensity of a Central Condensation separately from that of the overall coma).

Degree of Condensation would be more correctly presented if the coma were shown as steadily condensing from the edges to the center at ever increasing rates as the DC numbers increase, not as some manner of separate central mass within the coma. Likewise, a DC value of 9 (which is very rarely ever seen) would indicate the entire coma is so intensely condensed that it looks essentially stellar, or a tiny planet-like solid disk (and without much, if any, surrounding coma), even when viewed telescopically. It would not simply be a star-like feature within an otherwise small diffuse coma, as is presented here. Such a feature as shown would be classified as a 'star-like' central condensation, or "pseudo-nucleus" within the coma.

J.Bortle (former S&Ts Comet Digest editor)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 3, 2021 at 11:16 am

Dear John,

I read you for many years and learned much about comets from your columns, so I appreciate and value your comments about my DC value illustration. This might surprise you but my chart was based on the one you created for the International Halley Watch Amateur Observers' Manual for Scientific Comet Studies by Stephen Edberg (page 5-6). It's also informed by my own observations cross-referenced against those made by other comet observers over decades. You make a good point about the DC 9 value. Perhaps I shouldn't have included the small, faint outer coma. I only did based on observations of 29P at the start of an outburst, when it can appear like a tiny, solid disk with a DC=9. But even then there's often a bit of faint, diffuse haze surrounding that disk, though I have to agree, not quite as prominent as what I've shown. I will take it down a bit and repost the diagram. Thanks again, John.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John Bortle

September 4, 2021 at 11:57 am

Hi Bob -

I'm not sure just what I offered Steve Edberg for the Halley Watch publication nearly 40 years ago. I believe that I did do a more representative job of illustration for S&T's short lived observing guide published about 20-25 years back. Even better reference is offered in my drawings appearing in the International Comet Quarterly's GUIDE TO OBSERVING COMETS (1997), specifically figure 4.2 on page 78 therein. Also worthy of perusing as references are my stipple drawings of comets in that guide and subsequently in the ICQ JOURNAL.

I think a large part of the problem with the appearance in published drawings may lay in the manner in which shading drawings reproduce, which I often found difficulty with. The more subtle degrees of shading, seen in the original drawings, often seem to become lost, or blended out. This is why I largely switched to doing stipple drawings with Hyakutake's Great Comet and thereafter.

Re the appearance of 29P during outburst (many of which I followed back in the 1980's creating a new understanding of 29P's outburst cycle), when an outburst occurs after a long dormant period, the only thing seen initially is an isolated hard star. In the following days a tiny, planet-like disk evolves, eventually growing steady into an increasing diffuse cloud. If 29P appears as a star-like feature imbedded in a small, faint, diffuse glow it is only because the new outburst has appeared within the remnants of another, somewhat earlier, outburst. I have witnessed as many as 3 such "shells" of outbursts simultaneously!

John Bortle

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 5, 2021 at 8:48 pm

Hi John,

I just returned from a star party and greatly appreciate the references to your DC illustrations. I plan to look them up once I'm better rested! Thanks for bringing up 29P and your work in elucidating its outburst cycle. While at the gathering I learned from Graham Wolf that 29P had just undergone another outburst this weekend to mag. 12.2. You can imagine how eager I was to see it. How interesting that it displayed as a "hard star (very faint ~15.0)" in a coma about 30" wide — possibly the remnant of an earlier outburst in August. I will be watching it for shells should this be the case.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

OwlEye

September 7, 2021 at 12:09 pm

I have wondered about this DC question myself, and for quite some time. In the BAA's Comet Observing Section, 4.5, they have a set of drawings not unlike the ones in this post, and in addition are two labelled 2S and 3D, which illustrate for me the source of my own confusion. At the end of 4.5, the text reads, "Beware of confusion between the term 'central condensation' which just indicates that the coma is much brighter towards the centre and 'nuclear condensation' which is the nearly star-like feature only seen occasionally. A condensed comet doesn't have to have a nuclear condensation' ". What are your thoughts, gentlemen?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John Bortle

September 8, 2021 at 12:16 am

A fully detailed reply to your questions is going to require significant page space, which I don't have time tonight to pen. Give me a day, or two, and I'll get back to you here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

OwlEye

September 8, 2021 at 6:56 am

Thank you, John, I'll be watching for it. DZ

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John Bortle

September 11, 2021 at 3:19 pm

Owleye - Let me see what I can do with your questions without commanding too much page space here.

Firstly, as to the matter of DC, let me say that I judge it by the criteria largely set forth in the writings put down by the ALPO's Comet Section's first director, Dave Meisel, in the late 1950's, which the small group of us at the time adhered to from then forward. What written, or illustrated, guides offered at the time are long gone from any files of mine, but were enhanced through personal experience in extensively observing something like 300 comets of all appearances over nearly 50 years. Basically, I'd say that the ALPO's concept of DC likely derived from that outlined by British author J.B.Sidgwick.

As I've previously noted, shading drawing rarely can faithfully depict the full gradation in brightness levels across the comet's coma (which goes from the diffuse outer edges and increases steadily toward the center), thus making most (even some of my own drawings) misleading to use as reference. The drawings were done accurately, but the reproductions are not.

I do not have a copy of the BAA Comet Section guide, so commenting on the illustrations depicted therein is, at best, difficult. However, the images you cite showing coma's with DC's of 2S and 3D may refer to the combined DC/nucleus classifications proposed by C.S.Morris some years back. It attempts to describe not only the coma's DC, but also if it contains other features, like a nuclear-condensation, or nucleus.

As to the differences between 'central condensation' and ' nuclear condensation', the former indicates the presence of a distinct and reasonably separate mass present within the coma, as if a smaller and denser/brighter, more sharply condensed coma is situated within the larger, outer coma. Typically, this feature occupies only a modest percentage of the coma's overall diameter.

The center of the coma most commonly comes simply to a diffuse peak, but a 'nuclear condensation' appears like what Bob King depicts in his DC7 drawing: an almost star-like feature surrounded by a small, bright, dense mass is largely separated from the brightest coma beyond. If the feature is truly 'star-like' , then it is called a 'stellar condensation'.

I'm sorry if such terminology becomes more complex with each feature's appearance, but it is/has been that widely employed among the most experienced comet observers throughout the world for years in the ICQ. Without question, a proper written and correctly illustrated guidebook in need for this field of amateur work, but I fear too few of us old-timers are left today to make such a volume likely.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 11, 2021 at 5:46 pm

John,

Would it be possible for you to create an updated DC diagram? I would be delighted to use it henceforth. It would then be in the S&T archive and serve as the standard. What do you think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John Bortle

September 12, 2021 at 3:55 pm

Hi Bob - Is there somewhere on the S&T website where your e-mail address is listed? I would prefer to answer your query regarding creating a DC scale diagram therein, rather than on this open forum.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 12, 2021 at 4:46 pm

John,

Just sent you a message.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

OwlEye

September 9, 2021 at 1:32 pm

Thanks for another great list of comets to try for, Bob!

Day before yesterday, the NASA satellite loop showed a cold front approaching our area, with all the smoke being herded ahead of it. Behind the front was cleaner air than I have seen for months. I got the 12.5-inch outside that evening to cool down the optics, went to bed, and got up early. I was not disappointed - being greeted by the darkest and clearest sky I've seen in a long time.

Went after 4P/ Faye first, to give C/2019 L3 (ATLAS) time to get higher out of the KC metro light dome. Found it quite easily at 79 X - upping the power to 99 X improved the contrast nicely and revealed a slight elongation. Then, I went after ATLAS, and was surprised at how much easier it was even though it was in a brighter part of the sky. (My sky ranges from Bortle 5 to 8) I ran out of time to try for 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko . . . another morning, perhaps!!

Last night was gorgeously clear, and I used the same instrument to go after C/ 2017 K2 (PanSTARRS), but not a trace - way too faint for my skies. Fortunately it might, as you indicated Bob, be 6th magnitude next summer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 11, 2021 at 5:49 pm

Hi Doug,

Great to hear you spotted at least the two comets. I agree with your assessment of C/2019 L3. It's well condensed and stands out well even in less than ideal skies. Last weekend at a star party under dark skies 4P/Faye and 67P/C-G both displayed very obvious tails in my 15-incher.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

OwlEye

September 16, 2021 at 11:45 am

Hi Bob,

Another cold front squeegeed the smoke from our skies yesterday, and I rose early this morning and found 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko up near the Hyades quite easily with the 12.5-inch at 79 X. The best view was at 244 X with a 13 mm Nagler. The great contrast of this eyepiece made the tail elongation stand out. At times there seemed to be a twinkle in the brightest part of the inner coma (the seeing was not very good). I tried 397 X, and while that darkened the sky further, it also darkened the comet resulting in less contrast.

Greatly looking forward to C/2021 A1 (Leonard) come early December. It may possibly be 4th magnitude according to aerith.net!

DZ

You must be logged in to post a comment.

OwlEye

September 24, 2021 at 2:26 pm

Hi Bob,

COBS recently indicated that C/2017 K2 (PanSTARRS) had brightened slightly, and day before yesterday brought another cold front and even cleaner air than the previous one. A nice challenge awaited as astronomical twilight would begin at 8:14 pm local time (ending at 8:46 pm), and the moon would rise at 8:26. This permitted a very narrow window of nearly full darkness to try for K2. I had the 12.5-inch scope already on the comet field at 244 X by 8:14, and began a careful search of its exact position in relation to a few nearby stars: at first, nothing. Then, after a few more minutes passed, I tried again, and began tapping the telescope tube slightly to put the star closest to the comet in a back-and-forth motion. At 8:24 pm, using averted vision with the tapping, I could just barely make out a small, diffuse object moving in precise rhythm with that nearby star!

Last night, I attempted another look with the benefit of complete darkness, but just as the sun was setting the NASA GOES satellite showed bands of thick smoke moving eastward toward De Soto, KS, and they must have arrived just before I began the search. The field stars were murky compared to the night before: not a trace.

Finding K2 on the first, crisp evening of autumn made a nice start to the season!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.