Two spacecraft are heading for a close Venus encounter: Solar Orbiter passes by on August 9th and BepiColombo on August 10th.

Updates:

August 13, 2021: The Italian Spring Accelerometer onboard BepiColombo recorded the accelerations measured by the spacecraft as it passed Venus, and the team then sonified that data, shown in the video below. The sounds reflect the rapid change in reaction wheel velocity as the spacecraft felt the gravity of the planet, and the huge changes in temperature in the spacecraft structure.

ESA / NASA / NRL / SoloHI / Phillip Hess

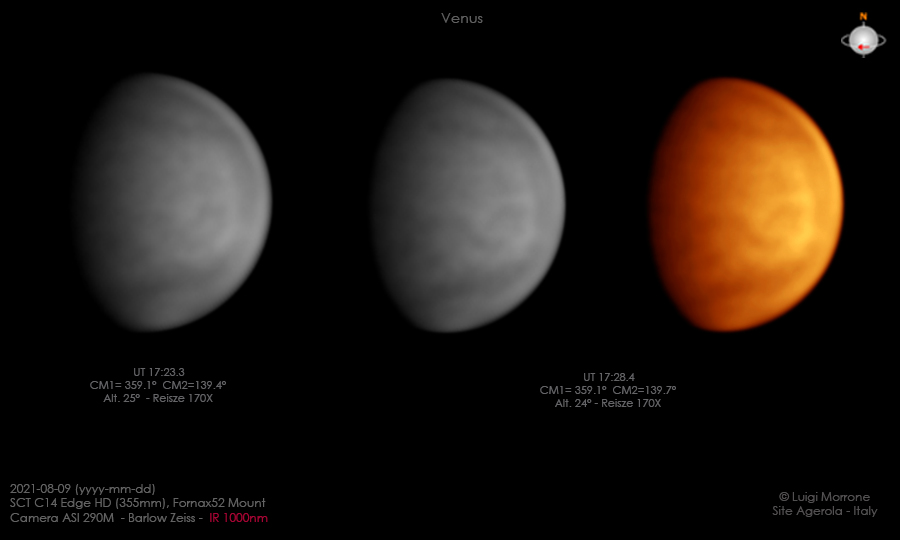

August 10, 2021: While Venus was not in a good position for Earth-based amateurs to image during the latest flyby, research scientist Kandis-Lea Jessup says, "We are always interested in amateur observations, even if the dates of observation are not directly coincident." The team contacted their most regular Venus observers for cloud tracking during the flybys. The Parker Solar Orbiter will be flying by Venus again on October 16th, and with Venus approaching maximum elongation, there will be a coordinated observing campaign October 6–20. Visit the Planetary Virtual Observatory & Laboratory for updates and campaign calls.

ESA

Venus is a brilliant beacon in the western sky after sunset right now. Look toward it and you will be looking at three spacecraft as well: Japan’s Akatsuki orbiter and two others, both European, that are fast approaching for their second gravity-assist flybys. Solar Orbiter passes by on August 9th and BepiColombo on August 10th. Both plan lots of science throughout their close encounters — and they are looking for amateurs’ photography to bolster their coordinated science campaigns.

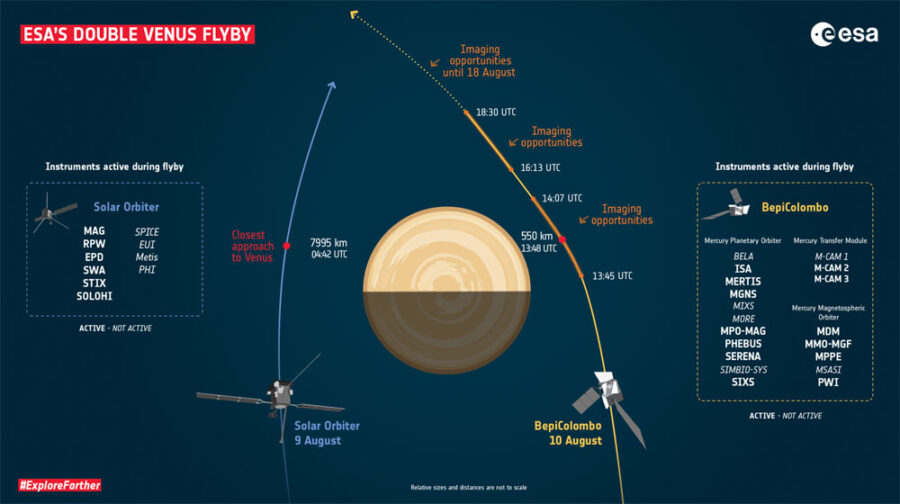

The two spacecraft are using Venus to steer them toward their eventual science targets. Both are approaching Venus from its night side, with the planet appearing as only the thinnest of crescents. But the flybys will achieve different results. After passing 7,995 km (4,968 miles) above Venus’s surface on August 9th at 4:42 UT (Earth received time), Solar Orbiter will speed outward from the Sun, aimed at a November 26th encounter with Earth. The Earth flyby will place it into its operational science orbit, beginning its prime mission.

Five more Venus encounters over the ensuing years will pump up the inclination of its orbit, allowing the probe to view the Sun’s poles. Only Ulysses has explored high solar inclinations within Jupiter’s orbit before, and Ulysses had no camera; Solar Orbiter, traveling much closer, will give us wondrous views.

Navigating a Flyby

BepiColombo, for its part, has to lose speed in order to drop in toward Mercury’s orbit. It will pass just ahead of Venus in its orbit on the way to a flyby at an altitude of 552 km on August 10th at 13:48 UT.

No spacecraft has passed so close to Venus since the end of the Venus Express mission in 2014. The many low-altitude orbits Venus Express took near the end of its mission have provided the European Space Agency (ESA) with a detailed understanding of Venus’s upper atmosphere, giving them confidence in handling their Mercury orbiter’s close passage.

Venus’s gravity will tug backward on the spacecraft, slowing it down and sending it on a path inside the planet’s orbit. Distances in the inner solar system being short, BepiColombo will fly past Mercury only 52 days later, on October 1st.

Into the Magnetosphere

Markus Fraenz (Max Planck Institute, Germany)

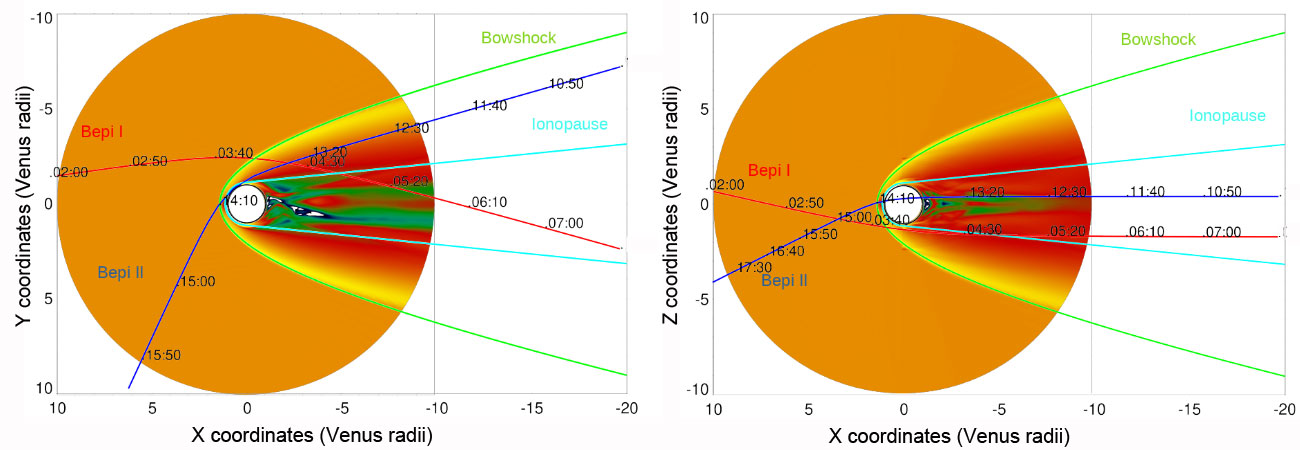

Akatsuki will observe Venus throughout the two flybys from the slowest, most distant part of its orbit, where it will monitor the behavior of Venus’s magnetosphere from a stable position. Venus, unusually for a planet, has no internally generated magnetic field. However, the solar wind interacts with the upper atmosphere, inducing a magnetic field. Where the solar magnetic field slams into Venus’ field, there is a bow shock, stretching out into a long magnetotail behind Venus. Solar Orbiter and BepiColombo will approach Venus from inside the magnetotail and pass across the bow shock just 33 hours apart, providing an unprecedented opportunity to directly measure how an induced magnetic field changes with time.

Both spacecraft have huge suites of instruments specially designed for studies of magnetic fields and the charged particles that travel within them, so the science payoff should be rich. Out in front of BepiColombo, Solar Orbiter will be able to measure variations in the solar magnetic field before they hit Venus’ field. Working together, the spacecraft will see how Venus’ magnetosphere responds to the Sun, nearly in real time.

All of Solar Orbiter’s fields and particles instruments will be powered on and operating in order to study the magnetic and charged-particle environment around Venus. Most of its cameras are intended for direct solar viewing so will not be able to image Venus during the encounter. The exception is SoloHI, a wide-angle, monochrome, visible-light camera that will usually be aimed off the disk of the Sun to capture the solar corona; it will image Venus’ nightside on approach.

BepiColombo will perform similar fields and particles measurements while inside the magnetotail. The extremely close pass also provides a test of the Italian Spring Accelerometer, designed to probe the deep interior of the planets by measuring subtle variations in the local force of gravity.

Around and after closest approach, BepiColombo will view Venus’s sunlit side, and the imaging instruments will get to work. MERTIS will get multispectral views until an hour after the flyby, using many wavelengths to penetrate the atmosphere to different depths. But the most fun images will come from the MCAMs, engineering cameras designed for spacecraft navigation and health checkups. MCAM2 and MCAM3 both look across parts of the spacecraft to space beyond. They’ll begin imaging three minutes before closest approach. MCAM2 will lose sight of Venus soon after, so will only take pictures for 22 minutes, but MCAM3 will watch Venus recede for 37 hours after the flyby.

ESA shares MCAM data to the web within 10 days of acquisition. Even before the images are released, ESA posts the metadata – image time and other information – which lets the public know how well the flyby has succeeded. Watch the ESA Planetary Science Archive to see when new images have landed! In an article posted today, ESA says that the first batch of BepiColombo image data will arrive in the evening of August 10th (European time), with most arriving on August 11th.

Related Links:

- Where to get Solar Orbiter data

- ESA Operations on Twitter

- Solar Orbiter on Twitter and on the web

- BepiColombo on Twitter and on the web

- Flybys page

3

3

Comments

Yaron Sheffer

August 3, 2021 at 7:23 am

What is "Earth received time"? The ESA website has no mention of this term.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

JimPollock

August 3, 2021 at 3:26 pm

I am only an amateur, so be warned. Venus is currently about 11 light-minutes away from Earth, which means that an event occurring or photo taken on Venus wouldn’t arrive at Earth for 11 minutes. Solar Orbiter will make its closest approach to the surface of Venus on Aug 29th at 4:31 UT (Universal Time). If it takes and transmits a photo at that time, it would arrive at earth 11 minutes later at 4:42 UT. Hence the “Earth received time” which is later than the actual flyby. (By a bit!) Jim in Bouldder

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

August 7, 2021 at 6:50 am

Yes, Jim, I am familiar with light travel time. My point is, if ESA does not specify it as "received" time, why is it mentioned here? Could it be the actual time at Venus, 11 minutes before reception?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.