A study of hundreds of Sun-like stars shows that most of them are more active than the Sun itself.

MPS / hormesdesign.de

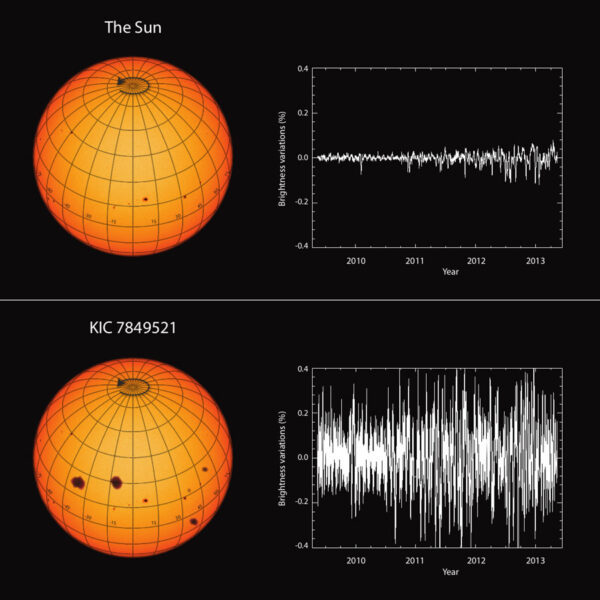

Our Sun is pretty slothful, compared to many of its stellar look-alikes. Sure, it has its occasional spots and flares, but they don’t alter the Sun’s energy output by more than 0.3%. In contrast, according to a new study published in this week’s Science, stars that look like solar twins in every aspect exhibit brightness changes that are five times as large as our star’s.

“This is an interesting paper and the results ring true,” comments solar physicist David Hathaway (Stanford University).

An international team led by Timo Reinhold (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Germany) searched the huge data set amassed by NASA’s Kepler space telescope for stars with Sun-like temperature, surface gravity, and composition. They then added distance measurements and other data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission to reveal the positions of the stars on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. This iconic plot of the stars’ luminosity and temperature made it possible to select only those with ages similar to the Sun.

Magnetic activity on a star’s surface is driven by stellar rotation. From tiny periodic brightness variations in the Kepler data (probably due to large sunspots rotating in and out of view), the team found 369 Sun-like stars with rotation rates between 20 and 30 days, comparable to our own Sun’s 24.5 days. What was surprising was that, most of these stars’ brightnesses fluctuated more than the Sun’s does.

The researchers also looked at a larger sample of 2,529 Sun-like stars for which no rotation rates could be derived, but which is expected to contain many stars rotating at rates similar to the Sun. The activity in this sample is comparable to the Sun's. Nevertheless, being Sun-like in every aspect apparently doesn’t guarantee placid behavior.

“[The result] fits in with ideas that the current solar dynamo is near a transition point between one dynamo type and another,” says Hathaway.

Solar physicist Mausumi Dikpati (University Corporation for Atmospheric Research) agrees. “It is likely evidence of stellar dynamos having different ‘regimes’ of stronger or weaker activity, which can last for many cycles,” she says. These changes could come from changes in the way the Sun’s rotation depends on depth.

It’s also possible there is no fundamental difference between the Sun and the Sun-like stars found in the Kepler data — it could be the Sun just hasn’t exhibited its full possible range of activity for quite a while. Studies of radioactive isotopes produced by cosmic ray particles reveal that our star hasn’t been substantially more active for the past 9,000 years or so than it is now, but, according to Reinhold, “compared to the entire lifespan of the Sun, 9,000 years is like the blink of an eye.”

According to Frederic Clette (Royal Observatory Belgium), the new result is of particular interest because it exploits a new rich stellar data set. “However,” he says, “it leaves a number of open questions, calling for a broader and finer study to firmly establish that the Sun is truly an anomaly.”

7

7

Comments

PGT

April 30, 2020 at 4:16 pm

If our Sun is "truly an anomaly," would change the likelihood of advanced forms of life on exoplanets?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Collin

May 1, 2020 at 4:46 pm

I would agree with PGT’s assessment, that advanced life could be statistically less likely than it might otherwise be given our unique circumstances, of which a stable solar system main star is one component. There are other odd aspects to us than that, like Earth’s huge moon relative to its size (largest satellite-to-planet size ratio, e.g.), but the Sun’s role as an exceptionally steady, stable energy source could play a factor.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Robert-LaPorta

May 4, 2020 at 1:00 pm

The supports the theory in the book "Rare Earth" which posits that while life itself may be common in the universe, the likeliness or intelligent life is extremely low.

For example dinosaurs existed for 10's of millions of years without any intelligence arising.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

May 6, 2020 at 3:47 pm

Dinos without any intelligence? Have you seen those Velociraptors in Jurassic Park? 😉

My opinion is that dinos were so successful at dominating the planet, that they had no need for human-like intelligence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

May 6, 2020 at 3:37 pm

In principle, yes. However, even those more active stars have activity levels that amount to mere fractions of 1%. I doubt that variations that small would significantly change the likelihood of (any) life forms on exoplanets in such star systems.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

May 2, 2020 at 12:44 pm

Lazy? Or smarter?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Scope58

May 19, 2020 at 12:01 am

This looks like classic selection bias, which was addressed, but not dismissed, in the study. Stars with big sunspots have big sunspots. No surprise.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.