Stellar mergers in quadruple systems might be common, a new study shows.

K. Teramura / University of Hawaii, Manoa

Star systems come in many configurations. Some are single like our Sun, but many others have one or more companions orbiting in a complex gravitational dance. Among such company, a stellar life can take an unexpected turn.

Take a recently discovered triple system, dubbed TIC 470710327, in which a close pair of stars is orbited by a third star. The outer star has more mass than the two inner stars combined, which poses a problem for theoreticians. Such a massive star ought to have started shining before the other two, and its intense radiation would have blown apart the gas around it — preventing the less massive pair from forming.

A team of astronomers came up with an original solution. What if the massive outer star used to be two smaller stars that merged shortly after they formed? The scenario, to be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint available here), not only explains this triplet’s configuration, but also demonstrates the complex pathways to star formation.

Three Stars, or Four?

Systems of three or more stars are not easy to spot. The system was masquerading as a known eclipsing binary until it was observed by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). It took the satellite’s precise measurements to notice that something else must be there, periodically pulling on the stars.

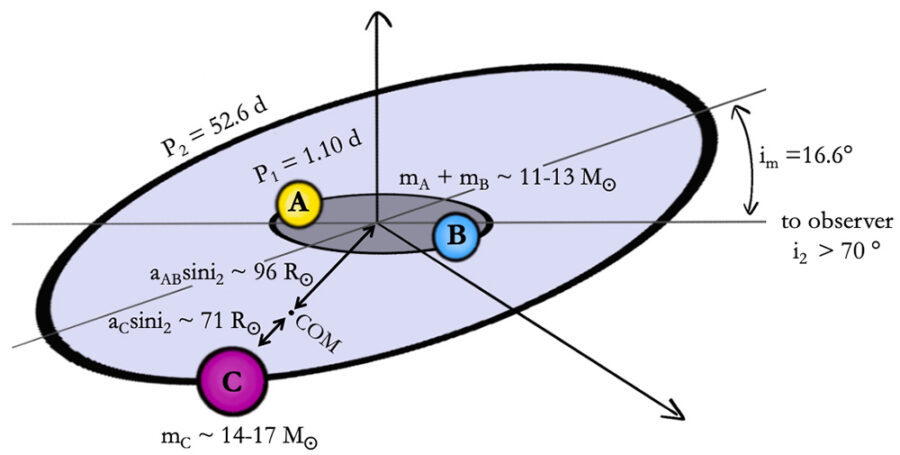

Scientists used the TESS data, complemented by other ground-based observations, to puzzle out the system’s properties. The binary consists of two stars orbiting each other with a period of about one day, and the tertiary star orbits the pair on an inclined orbit in about 52 days. The combined mass of the pair is less than 13 times the Sun’s mass, and the tertiary’s mass is somewhere between 14 and 17 solar masses.

N. Eisner / Monthly Notices for Royal Astronomical Society

This configuration is unique among known triple systems. “In most cases, the tertiary is of comparable mass or less massive than the binary,” says Maxwell Moe (University of Arizona), who wasn’t involved with the study. This triplet challenges formation models and calls for a unique solution.

In the new study, scientists supposed that the system began with two pairs of stars. Orbital behavior of isolated binary stars is usually predictable, but add another star or two to the mix and the orbits start showing complicated behavior. Periodic changes in the orbits’ elongation and inclination could alter stellar evolution and, in the most extreme case, merge some family members. And that was the scenario the authors were after.

“Similar models have been suggested for planets and low-mass stars, but we were the first to apply it on such a massive system,” said study lead Alejandro Vigna-Gómez (University of Copenhagen). The team simulated many binary pairs to show that, under certain conditions, it is indeed possible to merge the more massive binary and end up with a configuration similar to the one observed.

How to Recognize a Merger

In their models, the authors worked with four fully grown stars. However, it turned out that the merger had to happen very rapidly, suggesting that the stars could still have been in the process of development when the merger occurred, which could slightly affect the results.

Scientists are now faced with a difficult task: to prove that the tertiary is indeed a merged star. The team suggests look for signs of strong magnetic fields. About 7% of massive stars have strong surface magnetic fields, which some believe to have been amplified by past stellar mergers. While experts are still debating the link between mergers and magnetic fields, it doesn't hurt to look: the team is already taking additional observations of the system.

The authors make another prediction: The scenario they describe should lead to a deficit of highly inclined tertiary stars. As scientists discover more triplets, they may be able to confirm the model’s predictions on statistical grounds.

1

1

Comments

Willeau

July 17, 2022 at 7:04 pm

Though I agree with the possibility proposed here, I feel there are other possibilities that would better explain the near 17 degree inclination of the third star.

Isn't it also possible the larger star captured the other two after interacting with their system after a close approach. Perhaps one or both systems could have had other stars involved that were tossed out of the merged system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.