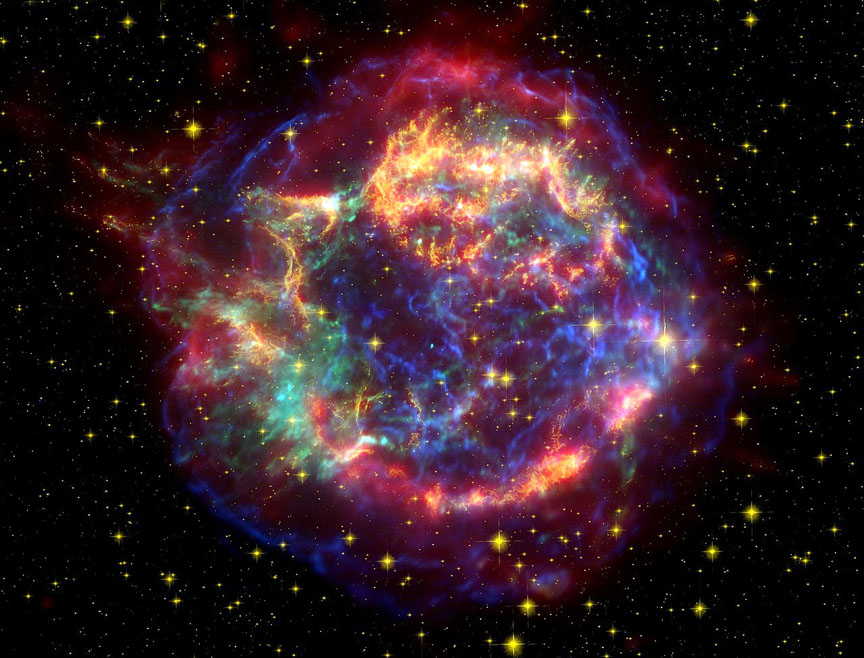

We still don't know for sure if anyone saw the supernova explosion in Cassiopeia around 1680, but there's no question we can observe what remains of it today.

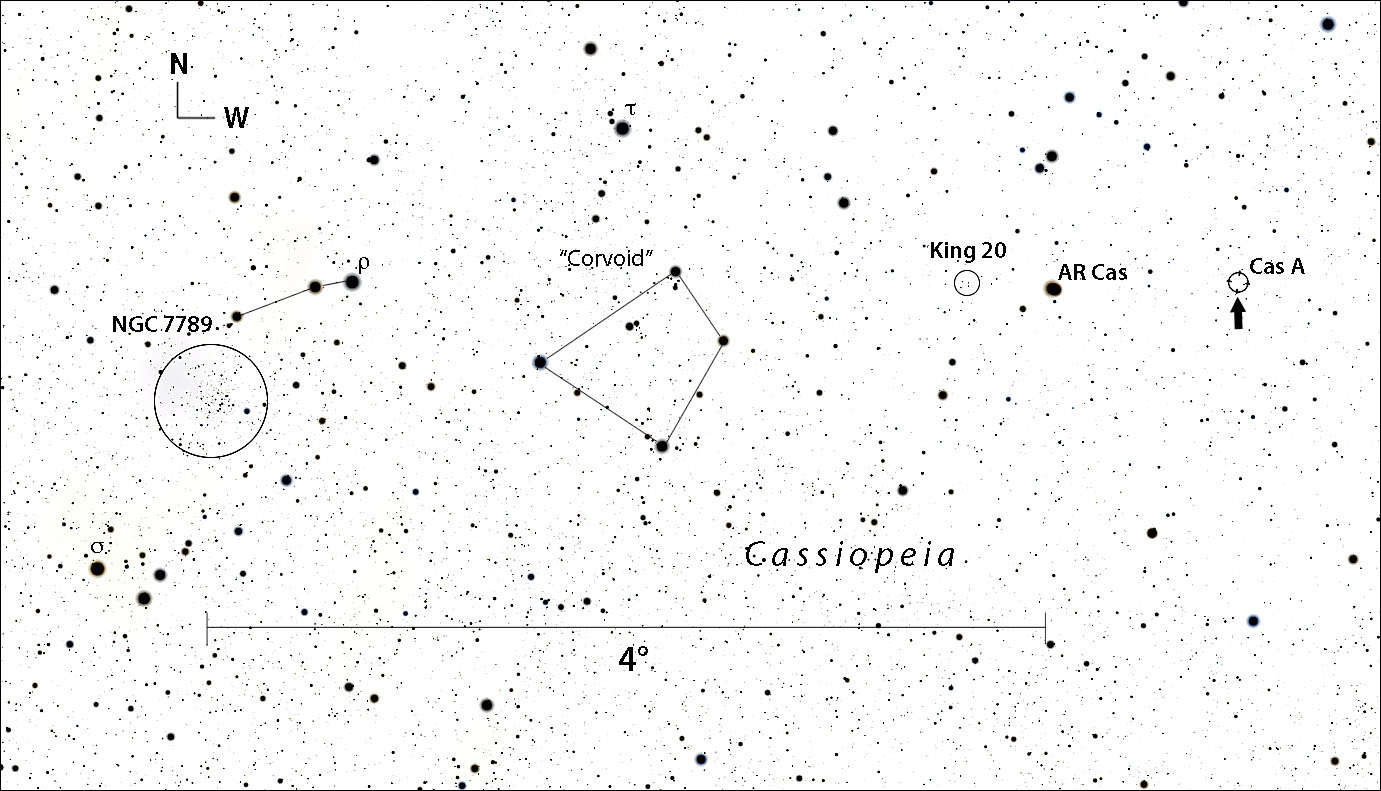

Stellarium

One night not long ago, I drove to dark sky with my 15-inch telescope to see if I could find the faint supernova remnant Cassiopeia A, or simply Cas A. I had always considered this remnant impossibly faint and off-limits for my scope, but read of others seeing it, so I put it on my list for a dark night when Cassiopeia arced high in the northern sky.

Located 11,000 light-years away within the Milky Way, the remnant formed in the aftermath of a Type IIb supernova, when a red supergiant with some 16 times the mass of the Sun reached the end of its life. After shedding its hydrogen envelope, the star's core collapsed and then rebounded, sending a shock wave through its outer layers that resulted in a massive explosion, blowing it to bits.

In its wake, a knotted arc of former star-stuff has been expanding outward from the explosion site ever since. Based on the speed of the ejecta, astronomers estimate the event occurred about 330 years ago, making Cas A one of the youngest supernovae known in the Milky Way.

NASA

My pilgrim's path to the explosion site began at NGC 7789, a rich and satisfying cluster of some 300 stars bright enough to spot in the smallest telescope. The dazzle of stars felt like a grand sendoff to parts unknown.

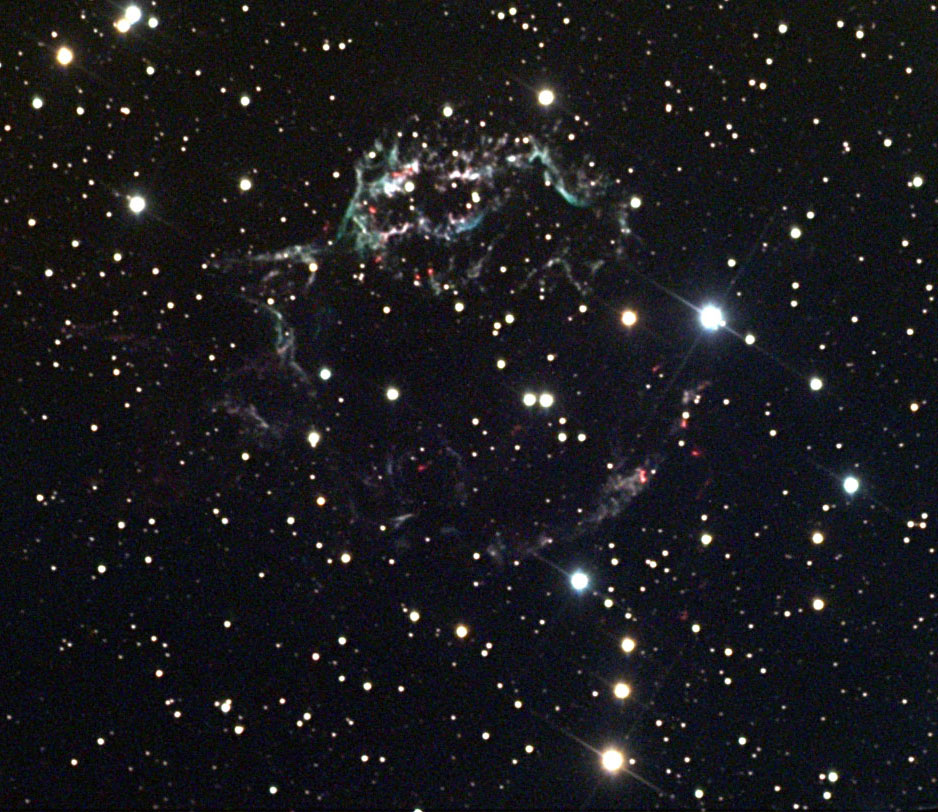

Charles Betts / Adam Block / NOAO / AURA / NSF

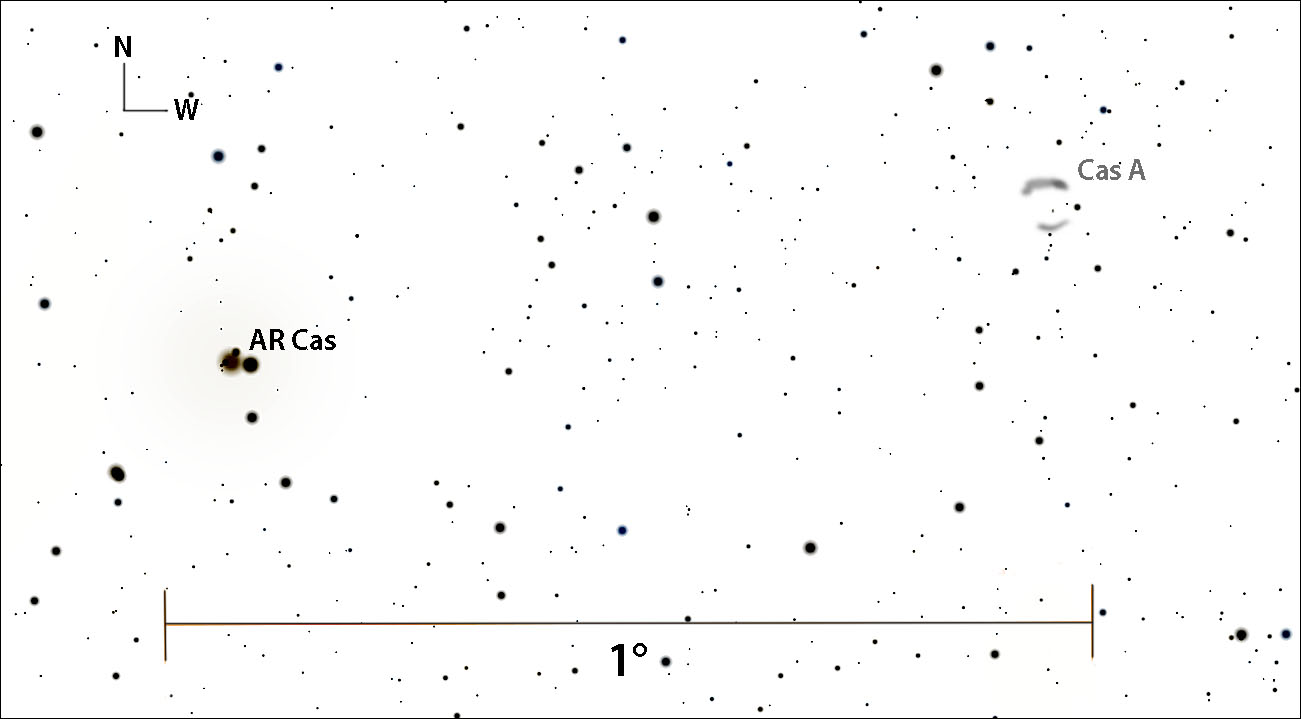

From here I star-hopped 3.5° southwest to King 20, a small but surprisingly rich, 4′ (arcminute) diameter open cluster immediately east of the magnitude-4.9 variable star AR Cas. Less than 1° farther southwest I stumbled on an ~1′ elongated tuft of nebulosity that resembled a small comet or galaxy.

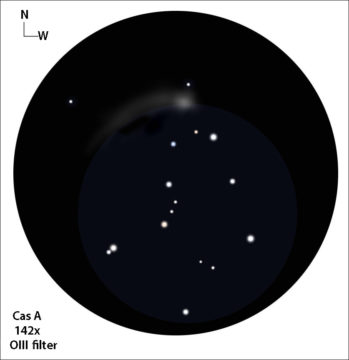

Bob King

The expanding supernova shock front compresses and collisionally ionizes the surrounding gas in the interstellar medium, causing it to fluoresce in wavelengths enhanced by nebular filters. To check my observation I applied an O III filter and watched with delight as the blob popped into better view.

With patience and averted vision I soon noted that an approximately 3-arc-minute arc extended eastward from the patch. I was seeing the northern half of the broken bubble revealed so clearly in time exposure photos. But despite numerous attempts with averted vision and different magnifications I failed to discern the fainter, patchier southern half of the remnant.

Given that the supernova behind the remnant would have flared into view sometime between AD 1660 and 1680, a time of feverish astronomical observation, why have there been next to no reports of it? A century earlier, Tycho's Supernova reached a peak magnitude of –4, nearly the equal of Venus and bright enough to cast faint shadows. Coincidentally, it flared into view just 9° to the southeast of Cas A. Yet the only observation we have of a "new star" at or near the position of Cas A in the right time slot was made by English astronomer John Flamsteed. In his Historia Coelestis Britannica star catalog published posthumously in 1725, Flamsteed recorded a 6th-magnitude star labeled as 3 Cassiopeia very near the position of the supernova.

Stellarium with additions by the author.

Other historians dispute this, noting that Flamsteed's position was 10 minutes of arc off, too far given the precision of his other stellar positions (within 0.3 arc minute) made at the same time. If we assume Flamsteed saw the supernova, why was it only dimly visible with the naked eye? Blame interstellar dust. In a dust-free line of sight, an explosion like Cas A would shine at magnitude –3, bright enough for all to see, but due to its location within the dusty plane of the Milky Way, it would only have reached magnitude 2 or 3.

Stellarium with additions by the author

We may never know why it was overlooked in an era when astronomers eagerly combed and cataloged the sky, but it's our 21st-century good fortune to see the continual unfolding of the massive explosion. Studies of the ejecta knots with the Hubble Space Telescope determined they're racing away from the center of the shell at speeds from 5,500 to 14,500 kilometers per second. More recently, NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory discovered a point-like X-ray source, called the Central Condensed Object (CCO), close to the remnant's center that appears to be a neutron star, the fantastically-compressed core of the original supergiant.

While I used a 15-inch scope to spot Cas A, I've read of others seeing it in 10-inch scopes under ideal conditions with nebular filters. My motto is to always bite off more than you can chew. With the Moon out of the sky the next dozen nights, seize the opportunity — you may surprise yourself!

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.