An icy moon torn apart in Saturn’s gravitational field some 150 million years ago could explain why the planet’s rings are so young and a host of other puzzles.

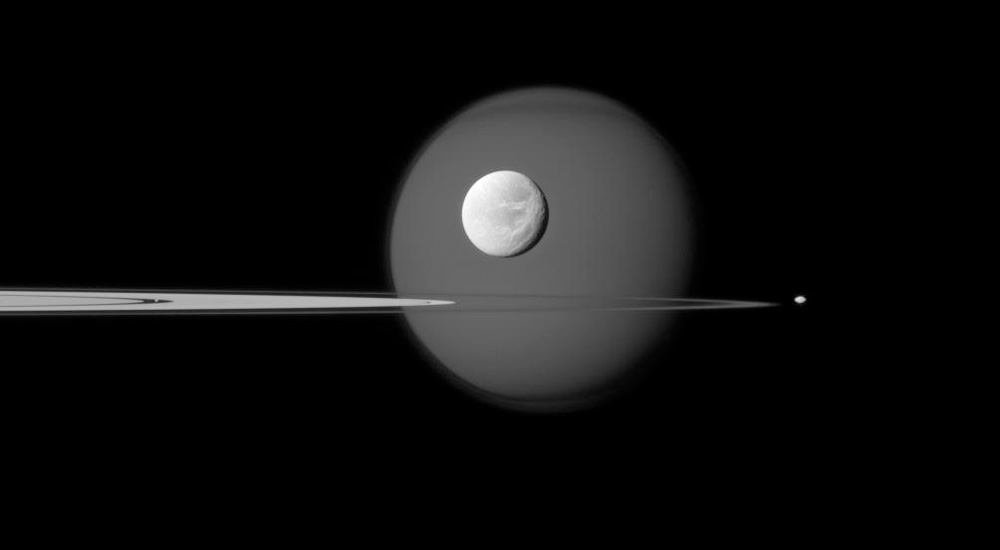

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

Just like a plain-looking pupa becomes a beautiful butterfly, a rogue moon of Saturn might have turned into the planet’s spectacular ring system.

In this week’s Science, Jack Wisdom (MIT) and his colleagues propose that tidal forces tore apart the unfortunate moon a mere 100 to 200 million years ago or so. The scenario could also explain Saturn’s axial tilt, and the somewhat elongated orbit of the planet’s largest moon, Titan. “It’s quite an innovative hypothesis,” says Jack Lissauer (NASA Ames), who wasn’t involved in the study.

Wisdom and his collaborators note that Saturn’s precession — the slow wobble of its spin axis — has almost, but not quite the same period as the precession of the orbit of Neptune. The researchers thus suggest there was once a true spin-orbit resonance between the two planets. The relatively rapid drifting-away of Titan (which currently spirals outward at about 11 centimeters per year) might have lowered Saturn’s axial precession period until the resonance locked in hundreds of millions of years ago. That’s when Saturn’s spin axis started to tilt, possibly up to 36°, according to the team’s calculations.

So how did Saturn escape the spin-orbit resonance with Neptune? Here, the story becomes a little speculative. Originally, the authors argue, Saturn might have had an additional moon that circled the planet between the orbits of Titan and Iapetus. When Titan drifted outward, this moon (aptly named Chrysalis by the team) became trapped in a 3:1 resonance with Titan, orbiting Saturn once for every three times Titan swung around. But the resonance didn’t last: Computer simulations show that the orbit of Chrysalis would have become chaotic, with the moon experiencing a couple of close encounters with both Titan and Iapetus before being ejected out of the Saturnian system, or ending up so close to the planet that it was torn asunder by tidal forces.

The elimination of an icy moon about as massive as Iapetus would suddenly change Saturn’s precession period, rescuing the planet from its spin-orbit resonance with Neptune. Saturn’s axial tilt (or obliquity) would start to decrease again (at present, it’s 26.7°). The earlier close encounters with Titan might explain this giant moon’s relatively high orbital eccentricity. And if Chrysalis was indeed ripped apart, Saturn’s impressive ring system may be part of its icy remains.

“We find that the loss of Chrysalis could have occurred roughly 100 to 200 [million years] before present,” Wisdom and colleagues write in Science. That fits in nicely with the young age that some researchers have previously suggested for Saturn’s rings. That age is based on the idea that the rings are so bright, even though impacts from micrometeoroids, interplanetary dust and cosmic rays should darken the rings over time.

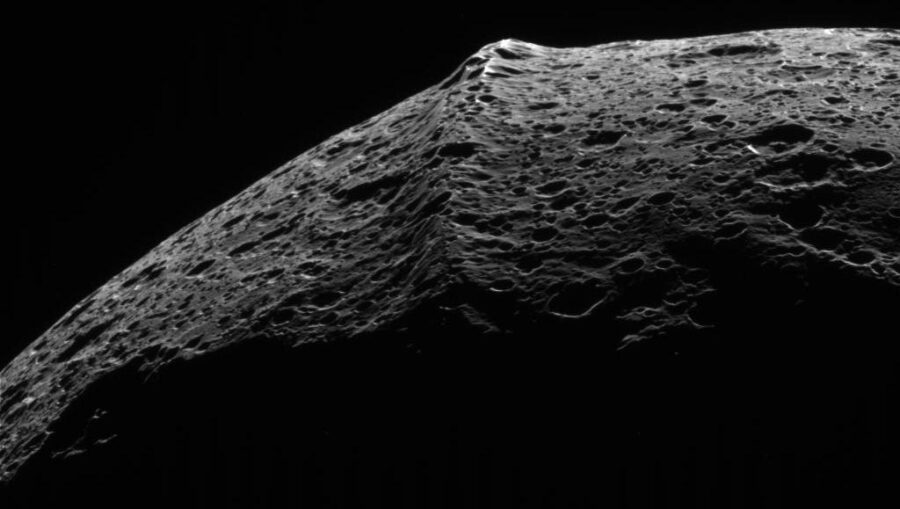

Asked whether the proposed Chrysalis scenario could possibly also explain the mysterious equatorial ridge of Iapetus, Wisdom replies: “We have not made [that] connection […]. But it is an interesting idea to contemplate.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

Luke Dones (Southwest Research Institute, Boulder) says he is “impressed that Wisdom and his colleagues can reproduce both the obliquity of Saturn and Titan's eccentricity. It’s a clever idea.” But, he adds, “they take for granted that the rings are young, which is not established. We don't know the dust impact rate on the rings, and we don't understand what happens when dust hits the rings at high velocities.”

Larry Esposito (University of Colorado, Boulder) agrees. “According to Sherlock Holmes, when you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,” he says. “My view is that it is still possible that the rings are old, so we are not forced to this improbable explanation. Overall, I’m not convinced.”

But in an accompanying commentary in Science, Maryame El Moutamid (Cornell University) describes the Chrysalis scenario as “a plausible mechanism for explaining Saturn’s close proximity to the precession resonance with Neptune and the seemingly young age of its rings.” And although Lissauer says he is “not convinced that it’s correct, nor that it’s wrong”, he says that the idea has “surprisingly many potential pluses.”

A better measurement of Saturn’s interior, gravity field, and precession rate might test parts of the Chrysalis scenario, according to Esposito and Lissauer. But Lissauer adds, “it’s really difficult to confirm.”

Read more about Saturn's mystifying moons in the September 2021 issue of Sky & Telescope, also available as a single-issue purchase.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.