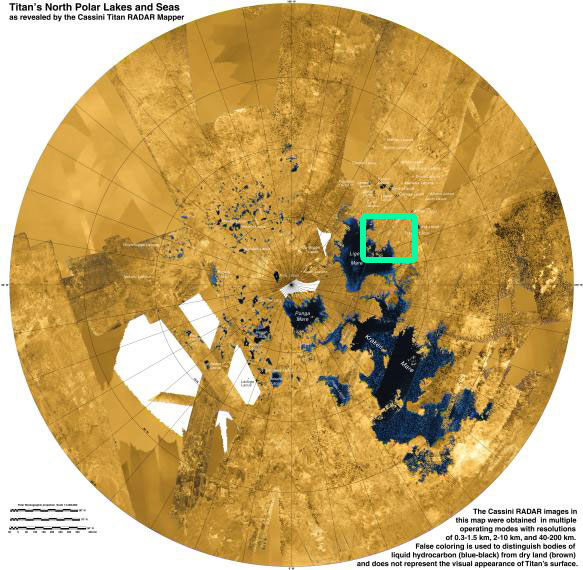

Cassini radar observations reveal a channel system on Saturn’s biggest moon, Titan, that is drowned in liquid methane.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASI / Cornell

The Saturnian moon Titan looks a lot like Earth. Seas, deltas, dunes — even hints of fog and rain. Except, it’s so cold on Titan that water is rock-hard ice; the liquid here is made of hydrocarbons, particularly methane.

Planetary scientists know that the seas on Titan are filled with methane, ethane, and perhaps other, similar compounds. They’ve also seen sinuous, river-looking channels that extend for hundreds of kilometers across the moon. One drainage network in particular, Vid Flumina, connects to Titan’s second largest sea, Ligeia Mare. Its channels look dark in radar images, leading researchers to suspect they’re filled with liquid. But scientists hadn’t proved that was the case.

Valerio Poggiali (University of Rome) and colleagues have now done just that. Using radar images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which arrived in Saturn’s neighborhood in 2004, the team did soundings of the features’ depths. The scientists found that the wiggly dark lines are in fact deep, steep-sided canyons, plunging up to 570 meters (1,870 feet) down. For comparison, the Freedom Tower in New York City rises 1,776 feet into the sky (if you count the beacon on top).

V. Poggiali / Geophysical Research Letters (DOI: 10.1002/2016GL069679)

The observations also caught reflections off smooth, presumably liquid surfaces at the bottom of the canyons. (I say presumably, but the flatness required is on the millimeter scale, so that’s pretty surely a liquid surface.) How deep that liquid is remains unknown.

The result is the first direct detection of liquid-filled channels on Titan, the team reports August 9th in Geophysical Research Letters.

The liquid filling Vid Flumina’s main trunk and tributary branches lies at sea level — specifically, the level of Ligeia Mare — even hundreds of kilometers away from the shoreline. A couple of other, sideline tributaries lie above sea level, suggesting they’re draining into the network.

Since the canyons are so narrow and deep (the sides slope at least 40°), they likely were cut into the ground slowly over time. The team’s two favorite explanations are (1) either the sea level was lower in the past, encouraging the flow to carve deeper to match it, or (2) tectonic uplift raised the terrain. The latter happened with Earth’s Grand Canyon.

For the curious (because I was): the Grand Canyon is 1,829 meters, or 6,000 feet, from rim to river at its deepest point. So in terms of the ratio of canyon depth to world radius, in some places the Vid Flumina system plunges deeper on Titan than the Grand Canyon does on Earth.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASI / USGS

You can read more about the discovery in JPL’s press release, or the release from the American Geophysical Union.

Reference: V. Poggiali et al. “Liquid-filled canyons on Titan.” Geophysical Research Letters. August 9, 2016.

Read more about Titan’s weather in S&T’s March 2013 issue.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.