What kind of planets are likely to ensnare comets coming in from the icy outer reaches of a planetary system?

Gravitational nudges can dislodge comets from the icy outer regions of a planetary system and send them on a collision course with the system’s planets. What kind of planets are likely to ensnare these inbound comets, and which are likely to wave them away?

R. Evans, J. Trauger, H. Hammel and the HST Comet Science Team and NASA

Comets on the Move

When the interstellar object ʻOumuamua sped through the solar system, its arrival confirmed what many astronomers had long suspected: space is teeming with debris that has been kicked out of planetary systems by gravitational interactions.

But the same gravitational interactions that can launch comets into interstellar space can instead send them careening into the inner regions of the planetary systems where they were born. When that happens, the comets can settle into new orbits, be consumed by their host star, or, as a new publication explores, be accreted by the planets in the system. What determines whether a planet will collect comets that wander close to it, and how might the accretion of comets affect our interpretation of exoplanet spectra?

Alan Fitzsimmons (ARC, Queen’s University Belfast), Isaac Newton Group

Accreted or Scattered?

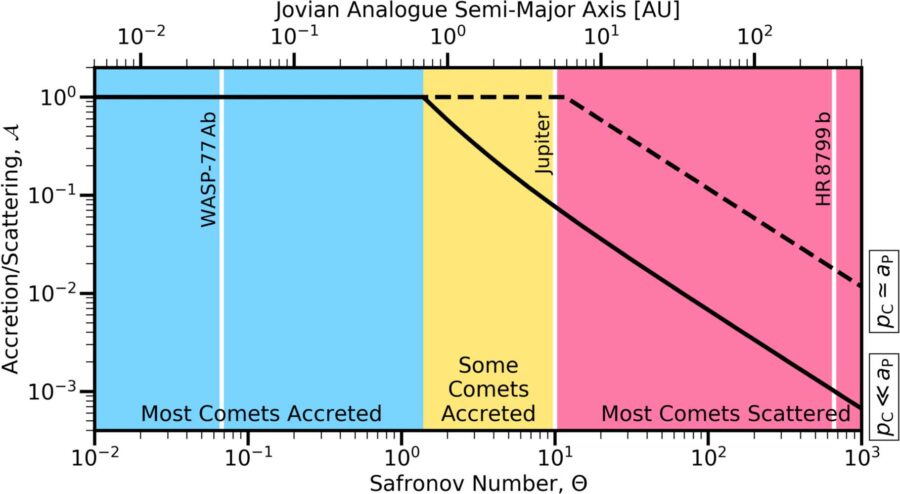

A team led by Darryl Seligman (University of Chicago) developed a set of equations that predict which planets are most likely to accrete inbound comets. The equations describe the likelihood of a planet accreting a comet into its atmosphere or scattering a comet into a new orbit (or out of the system entirely) as a function of the properties of the planet — its mass and orbital distance — and those of the comet — mainly its eccentricity, which is a measure of how circular or elongated its orbit is.

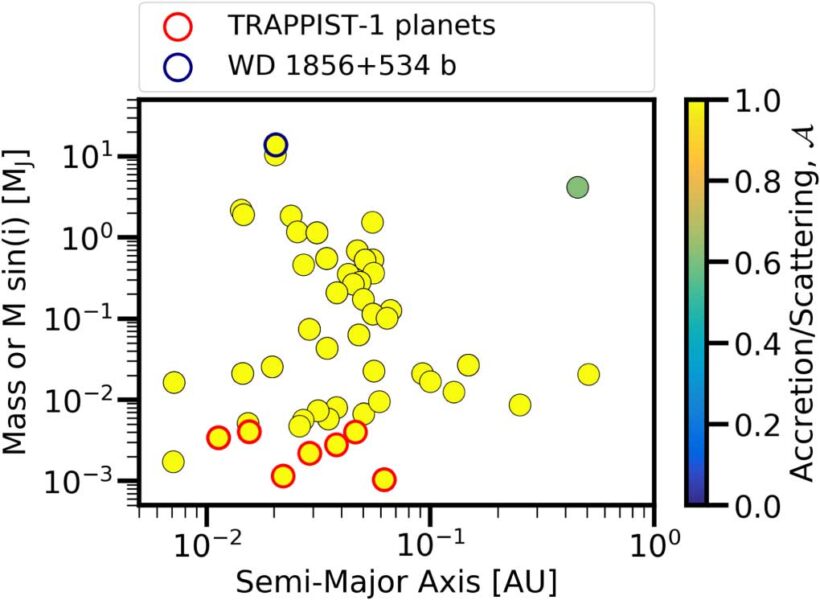

The team used their metric to determine which of the previously detected exoplanets are likely to have added cometary material to their atmospheres. Seligman and collaborators found that, in general, planets categorized as warm Jupiters, super-Earths, and sub-Neptunes are more likely to ensnare passing comets than colder, more massive planets.

Seligman et al. 2022

Composition Imposition

What does it mean for our understanding of distant planetary systems if exoplanets accrete a large amount of cometary material? Potentially, quite a lot! Planetary composition is thought to relate to where in a protoplanetary disk a planet formed. However, if planets accumulate cometary material — which bears the chemical signature of having formed far out in the disk — estimates of a planet’s birthplace based on its atmospheric composition might be inaccurate.

Seligman and collaborators note several reasons that their estimates are likely an upper limit on the amount of cometary material that planets accumulate. For example, if comets in other planetary systems tend to disintegrate or lose their volatile compounds quickly, the likelihood of exoplanet–comet encounters — and the effect they have on an exoplanet’s atmospheric composition — could drop.

Seligman et al. 2022

This issue is a timely one, since based on the team’s metric, nearly all of the exoplanets that JWST will observe within the next year have the potential to have accreted cometary material.

Citation

“Inferring Late-stage Enrichment of Exoplanet Atmospheres from Observed Interstellar Comets,” Darryl Z. Seligman et al 2022 ApJL 933 L7. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac786e

This post originally appeared on AAS Nova, which features research highlights from the journals of the American Astronomical Society.

2

2

Comments

Bob-dBouncier

July 25, 2022 at 11:07 am

"What kind of planets are likely to ensnare comets coming in from the icy outer reaches of a planetary system?"

I don't want to say the answer is trivial - the math, while straightforward, is fairly complex. But it does seem intuitively obvious that planets with the largest gravity are most likely to affect the bodies they encounter, be they comets, asteroids, or random rocks.

The problem has been solved many times before. When each manned mission was returning, there would always be an explanation of the reentry margin for error: too steep, and you burn up; too shallow, and you bounce out into space. Speed was a large component as well. Even the movie Apollo 13 had a section where they realized the missing weight of anticipated moon rocks was affecting their return.

The planet data is known, so it's just a matter of discovering a particular body's relative orbit, mass and speed, to determine its probability of being ensnared. Then generalizing this over a given range of possibilities for each planet. Since the Sun has the largest gravity, it will 'win', and its effect will draw things into the inner system, giving the smaller planets their chance to be 'in the way' of an inbound body.

All in all, an interesting exercise. Maybe a model could be used to guess which will happen first: the solar system emptying the Oort Cloud, or the Sun swallowing up everything.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

July 25, 2022 at 2:03 pm

A very interesting report and graphs, example Safronov number. The most comets accreted falls in the range 0 to 1 AU from the host star. I checked this exoplanet site, https://exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu/index.html

5063 confirmed. When I use my MS ACCESS DB running MS SQL query, 4145 unique exoplanets report for duty using 0 to 1 AU 🙂 Looks like an abundance of exoplanets documented now very close to their parent stars for testing including comet accretion in our solar system from Earth to Mercury 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.