Four eclipses occur in 2021, with annular and total solar eclipses alternating between total and not-quite-total lunar eclipses.

Guillermo Abramson

Up to seven eclipses of the Sun and Moon can take place in one year, though the last time that happened was 1982, and the fewest possible is four.

That latter, minimalist mix is in play for 2021 — but it’s a good assortment. The two solar eclipses will be “central” events (annular in June and total in December). Meanwhile, in May we’ll witness our first total lunar eclipse since January 2019, and the one that follows in November just misses being total. Even better: Three of these four are visible from somewhere in North America. To learn which ones, read on!

Why Do Eclipses Happen?

Jay Anderson

A solar eclipse, such as the one seen coast to coast across the U.S. in August 2017, occurs only at new Moon, when the lunar disk passes directly between us and the Sun and the Moon’s shadow falls somewhere on Earth’s surface.

Conversely, a lunar eclipse takes place during full Moon, when our satellite passes through Earth’s shadow.

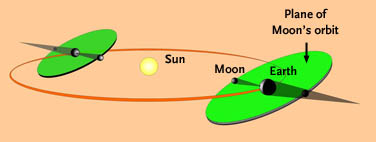

These alignments don’t happen at every new and full Moon because the lunar orbit is tipped about 5° to Earth’s orbital plane — only occasionally do the Sun, Earth, and Moon line up exactly enough for an eclipse to occur. (The technical name for that, by the way, is syzygy.) And, as the diagram above implies, those alignments occur roughly six months apart. In 2021, for example, one solar eclipse occurs in June and the other in December.

Lunar Eclipses

Three types of lunar eclipse are possible (total, partial, and penumbral), depending on how deeply the full Moon plunges into or near the umbra, our planet’s dark, central shadow.

Johnny Horne

If the Moon goes all the way in, we see a total lunar eclipse that’s preceded and followed by partial phases. That was the case during the widely viewed event in September 2015, which marked the conclusion of a series of four consecutive total lunar eclipses in 2014–15! Such eclipse tetrads are not common — the last one occurred during 2003–04, but the next won’t begin until 2032.

If it part way into the umbra, as pictured above, only the partial phases occur — you’ll see part of the Moon in nearly full sunlight, and part of it steeped in the deep, red-tinged umbral shadow.

And if its disk passes just outside the umbra, it still encounters the weak penumbral shadow cast by Earth. A sharp-eyed observer will notice that one side of the full Moon’s disk looks a little dusky. All four of 2020’s lunar eclipses were of the penumbral variety.

Fortunately, every lunar eclipse is observable anywhere on Earth where the Moon is above the horizon. (But there’s still an element of luck involved — after all, the sky has to be clear!)

Solar Eclipses

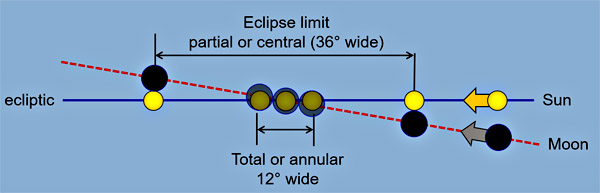

Annular and total solar eclipses require the Moon to cross directly in front of the Sun as seen from Earth — and, as the graphic below shows, such “central” solar eclipses can only occur within a two-week-long interval when the Moon crosses the ecliptic during one of its two nodal crossings each year. However, the node-crossing “season” for partial solar eclipses is wider, roughly five weeks long.

Jay Anderson

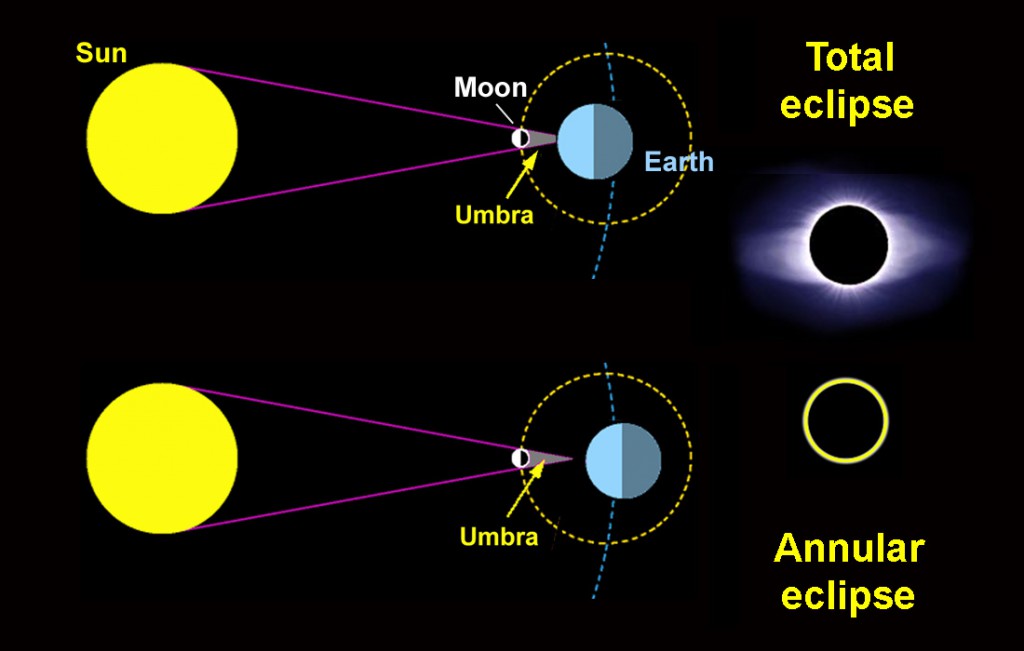

If the Moon completely hides the Sun, the eclipse is considered total. With its brilliant disk completely covered, the Sun’s ghostly white outer atmosphere is momentarily revealed for durations from seconds to several minutes. In November 2013, for example, planeloads of eclipse-chasers converged in a remote portion of northern Kenya to watch just 11 seconds of totality. What dedication!

Unlike total lunar eclipses, which can be viewed from roughly half of Earth’s surface, total and annular solar eclipses tightly restrict where you can see them because the Moon casts a smaller shadow than Earth does — and you need to be within that shadow to view the event. Everywhere on Earth experiences a total solar eclipse every 375 years on average, with the Northern Hemisphere enjoying a slight statistical advantage right now. (To explore the worldwide distribution of total eclipses more closely, check out Sky & Telescope’s beautiful eclipse globe.)

Sky & Telescope / Kelly Beatty

A completely eclipsed Sun can be viewed only from a narrow track or path on Earth’s surface that's typically just 100 miles (160 km) wide. Outside of that path, about half of the daylit hemisphere of Earth is able to watch a partial solar eclipse as the Moon obscures a portion of the Sun.

Occasionally the Moon passes directly in front of the Sun but doesn’t completely cover it. When that occurs, it’s usually because the Moon is farther from Earth than its average distance. (The Moon’s orbit isn’t perfectly circular; its eccentricity is about 5%.)

This geometric circumstance is known as an annular eclipse, so-called because you can see a ring, or annulus, of sunlight surrounding the lunar disk. Annular eclipses of the Sun occur about as often as the total ones do, and an annular’s path is likewise narrow. Outside of it observers see only a partial cover-up.

The Four Eclipses of 2021

Below are brief descriptions of the four eclipses that take place in 2021. You’ll find more details in Sky & Telescope magazine or on this website as the date of each draws near. Times are given in Universal Time (UT) except as noted. Adjust these to get those for your time zone: for example, PST = UT – 8, and EST = UT – 5. (But be sure to allow for daylight or “summer" time: PDT = UT – 7, and EDT = UT – 4.)

| Date | Type | Maximum | Visibility |

| May 26 | Total lunar eclipse | 11:19 UT | E. Asia, Australia, W. North America |

| June 10 | Annular eclipse | 11:01 UT | Canada, Greenland, Siberia |

| November 19 | Partial lunar eclipse | 9:03 UT | E. Asia, Australia, N. and S. America |

| December 4 | Total solar eclipse | 4:08 UT | Southern Ocean, Antarctica |

May 26: Total Lunar Eclipse

Sky & Telescope; source: USNO

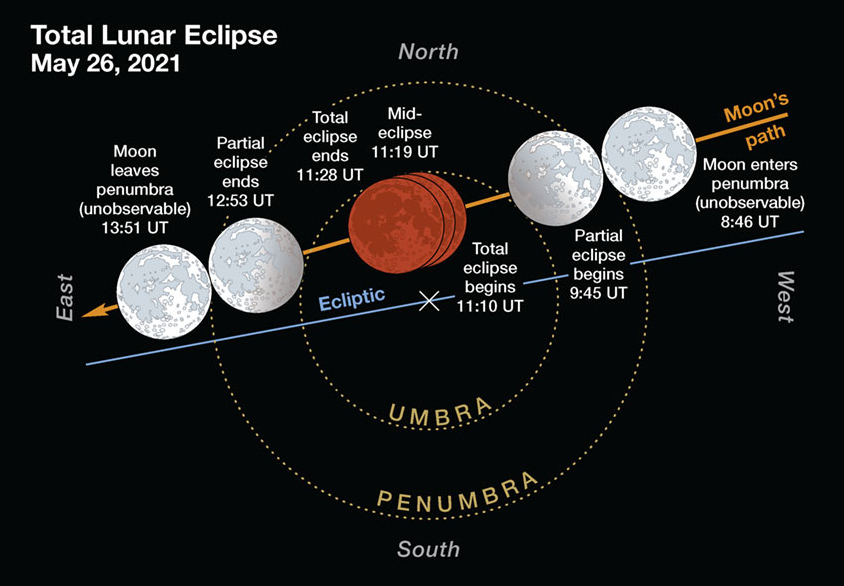

The year’s first eclipse doesn’t occur until the 146th day of 2021, but it’ll be a good one: It’s the first total lunar eclipse in nearly 2½ years. The timing benefits anyone living around the Pacific Ocean. Mid-eclipse takes place after sunset for easternmost Asia, Australia, and New Zealand; around 1 a.m. in Hawaii; and before dawn in western North America and from the tip of South America. Those in eastern North America have to settle for glimpsing the last partial phases before dawn — or maybe nothing at all.

This is not be a particularly “deep” eclipse, as the entire Moon just barely becomes fully engulfed by Earth’s umbra. Those able to witness totality should look for a distinct brightening on the northern half of the lunar disk. Also, the eclipse occurs with the Moon positioned in the head of Scorpius, so watch for the summer Milky Way to eerily emerge into view at mid-eclipse even though the full Moon completely overwhelms it just an hour before or after the eclipse takes place.

June 10: Annular Solar Eclipse

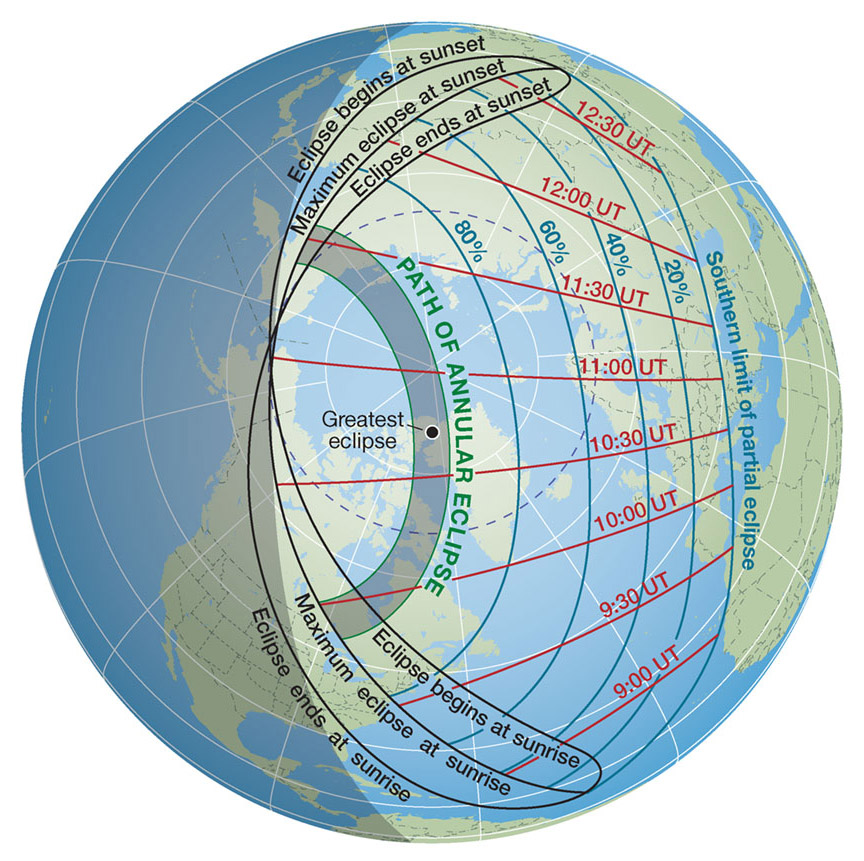

Sky & Telescope; source: Fred Espenak

Two weeks after May 26th’s total lunar eclipse — after the Moon’s phase evolves from full to new — the Sun, Moon and Earth again line up to create an annular solar eclipse on June 10th. (Notably, last year an annular eclipse occurred on June 21st.) As the global map above shows, viewing this event at its best will be challenging. The lunar shadow touches down in southern Canada at dawn before racing northeastward across Hudson Bay, northwestern Greenland (where annularity is longest, 3m 51s), the North Pole, and eastern Siberia.

Those in the U.S. Northeast and eastern Canada have a chance to see the Sun rise as a partly eclipsed disk — 73% covered from Boston, for example. Here’s a timetable for selected cities in North America (click on “North America” in Section 2). Virtually all of Europe and Asia are also positioned to experience a partial eclipse.

| Sky & Telescope is sponsoring an exclusive chartered flight to view June 10th’s annular eclipse from southern Canada. Please check here again for a link that will provide more details and pricing. |

November 19: Partial Lunar Eclipse

Sky & Telescope; source: USNO

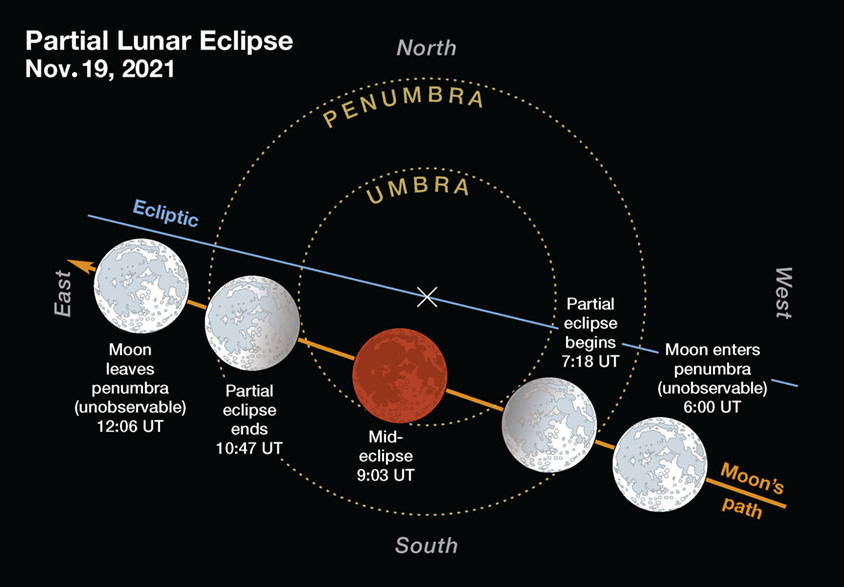

The geometric circumstances for the year’s second lunar eclipse are interesting. Rarely does the Moon plunge so deeply into Earth’s umbra without being completely engulfed. In this case, at mid-eclipse 97.4% of the lunar disk lies inside the umbra and the remaining 2.6% just outside in the deepest part of the penumbra. Consequently, the interplay of shading and color across the Moon’s eclipsed face promises to be especially entertaining.

Weather permitting, everyone in North America gets to view November 19th’s lunar eclipse — though not at particularly convenient times. As the diagram above shows, mid-eclipse occurs at 9:03 Universal Time, which corresponds to 4:03 a.m. Eastern Standard Time and 1:03 a.m. Pacific Standard Time. (Maybe we should all plan a trip to Hawaii, where the eclipse peaks at a more reasonable 11:03 p.m. on the evening of November 18th.)

Throughout this not-quite-total eclipse, you might consider performing a bit of “citizen science” by using a telescope to study the progression of the umbra’s abrupt edge across the lunar disk and to record the times when it covers or uncovers particular craters. Here’s an introduction to making these crater timings and other worthwhile observations during a lunar eclipse.

December 4: Total Solar Eclipse

Sky & Telescope; source: Fred Espenak

The final eclipse of the year is the one that “umbraphiles” the world over are waiting for. You’ll perhaps recall that the Moon’s umbral shadow swept across central Chile and Argentina last December — but the global pandemic prevented virtually everyone from traveling to see it. Even for those already there, a nasty rainstorm blocked the view of totality from within the path in Chile.

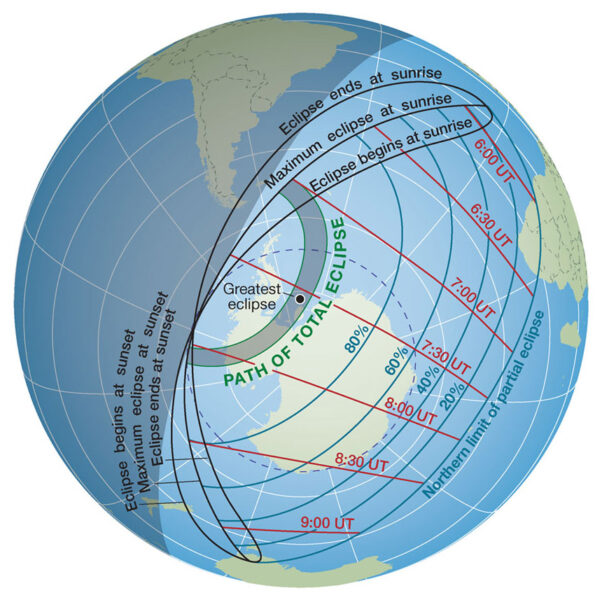

So eclipse-chasers are planning to head once more to the Southern Hemisphere for the total solar eclipse on December 4th. Unfortunately, Mother Nature has again dealt them challenging circumstances. As the map above shows, the path of totality is restricted to vast tracts of the Southern Ocean and Antarctica. The greatest duration of totality, a modest 1m 54s, occurs off the Antarctic coast in the Weddell Sea.

Partial phases will just barely be visible from southernmost Africa, southeastern Australia (a scant 2% in Melbourne), and Tasmania.

This eclipse occurs just 17 days before December’s solstice, so virtually everything poleward of the Antarctic Circle is bathed in constant sunlight. Look closely at the global map, and you’ll notice that the path of totality falls on the “nighttime” (anti-sunward) longitudes of Earth. Consequently, the lunar shadow will move over Earth’s surface from east to west, rather than the expected west to east. This quirky geometry last occurred during the total solar eclipse on November 23, 2003.

Since December 4th’s eclipse happens near the peak of austral summer, many cruise ships are planning to position themselves in the path of totality. But according to Jay Anderson, a veteran meteorologist and diehard eclipse-chaser, the weather prospects where the path crosses the open ocean are not encouraging. One spot offering a better-than-average chance of clear skies is the group of tiny South Orkney Islands, which barely lie withing the umbral path.

| Sky & Telescope offers two opportunities to view December 4th’s total solar eclipse. You can choose either an exciting 18-day cruise adventure that includes setting foot on Antarctica — or a tour of Chile’s breathtaking Patagonia region that culminates with an airborne intercept of the totally eclipsed Sun. |

Looking Ahead to 2022

Diehard solar-eclipse chasers are scrambling to see one of the events in 2021, because next year offers only two partial solar eclipses (April 30th and October 25th) — and the next total solar eclipse isn’t until April 20, 2023. Prospects for Moonwatchers are better in 2022, with total lunar eclipses on May 16th and November 8th. Even so, that’s once again just four eclipses in all of 2022.

1

1

Comments

Yaron Sheffer

February 3, 2021 at 5:13 pm

So let's end on a more positive note... we are now closer in time to the next "American" solar eclipse in 2024, than we are to the last one that awed us in 2017 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.