These are the nights to get ready for the auroras — and tonight may be your lucky night. Not only is the current solar cycle swiftly intensifying, March is one of the best times of the year to see the northern lights.

Bob King

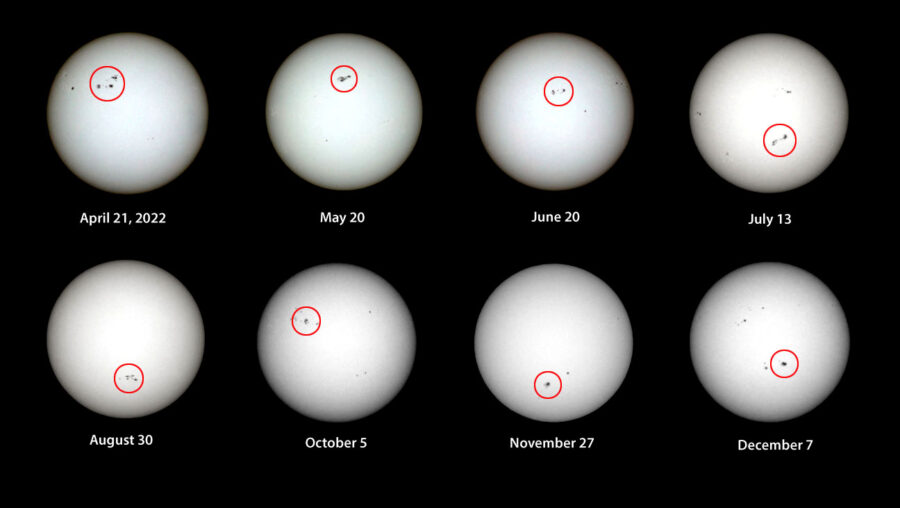

After a gradual decline in solar activity over the past few solar cycles, the current Cycle 25 appears to be bucking the trend and spawning more sunspots than originally anticipated. I can attest to the increase. Regular checks with my #14 welder's glass have netted naked-eye sunspots nearly every month since last spring. Escalating solar activity is often tied to more frequent and intense aurora sightings with displays penetrating deep into U.S. mid-latitudes.

Bob King

In complex sunspot groups magnetic fields can cross and tangle, resulting in a catastrophic release of energy called a solar flare. Occasionally, a flare can propel vast amounts of solar plasma into space as coronal mass ejections (CME). Should the blast cloud sweep past the Earth — the fastest arrive in just 15 to 18 hours, most take a few days — and link into the planet's magnetosphere, it can ignite a geomagnetic storm resulting in spectacular auroras. The same is true for filaments — serpentine forms of relatively cool, dense plasma suspended in the Sun's chromosphere by magnetic fields. Seen against the Sun they appear dark but when viewed at the solar limb they shine as brilliant red prominences. Instabilities in their magnetic "bedding" will sometimes launch one of these plasmic pythons into space as a CME.

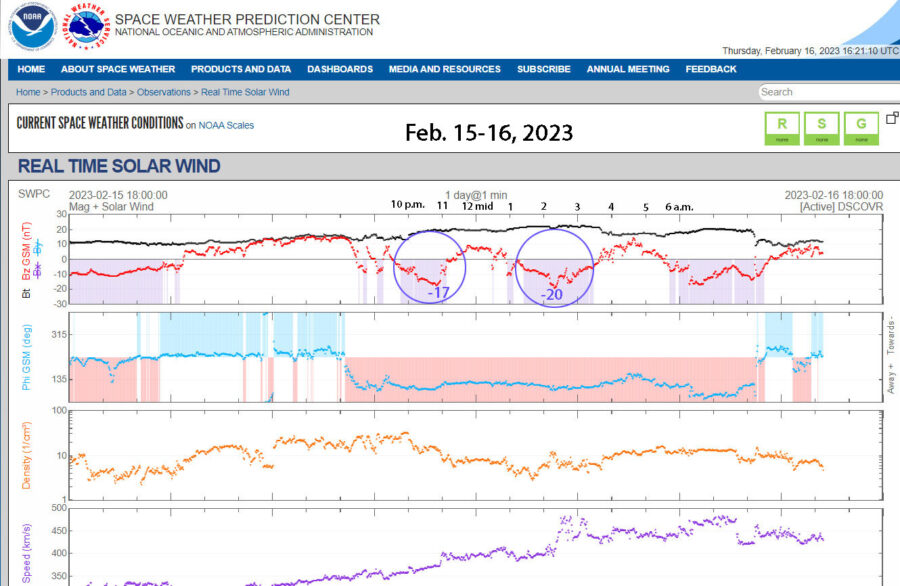

NOAA / SWPC with annotations by Bob King

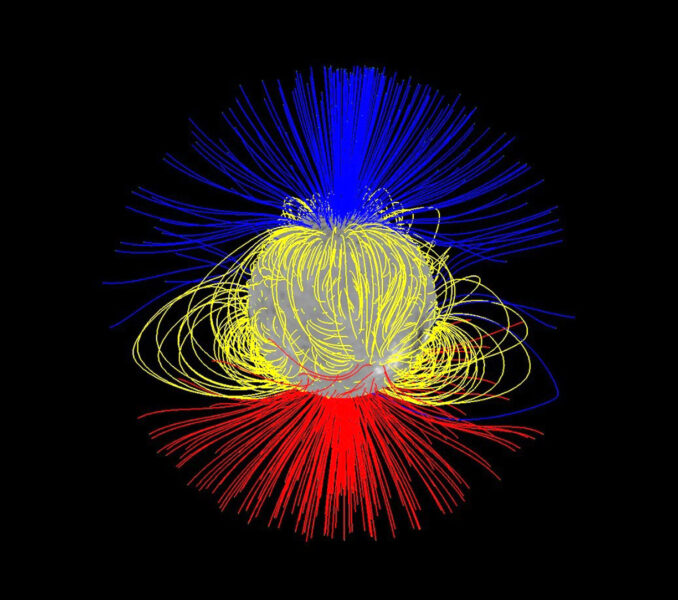

Even around solar minimum, gaping chasms called coronal holes in the Sun's magnetic canopy release pent-up plasma in high-speed gushers. When directed toward Earth the material can spawn modest displays of the aurora. What's more, these holes can persist for multiple solar rotations, sparking repeated auroral displays about every 27 days. Solar flares, filament ejections, and coronal holes are just some of the tools the Sun uses to rattle Earth's magnetic defenses.

NOAA

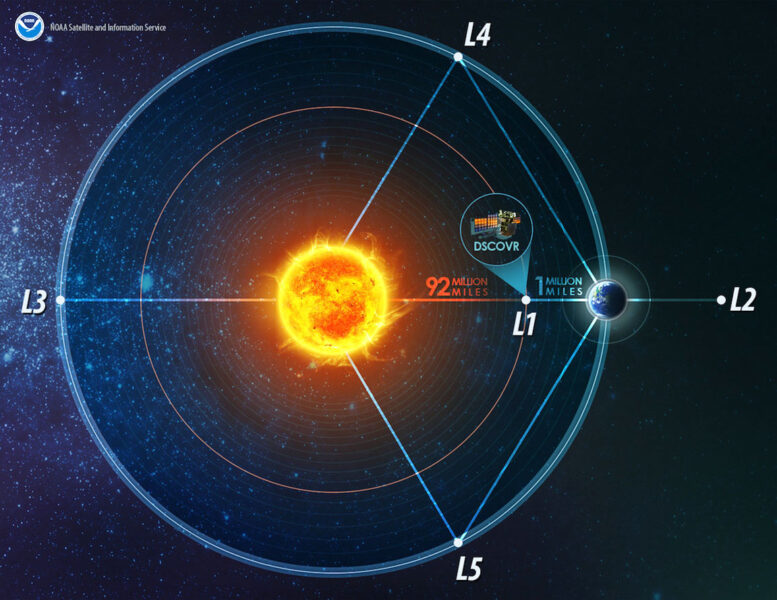

NASA's Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), situated at the L1 Lagrangian Point some 1.5 million kilometers sunward of the Earth, monitors the continuous stream of charged particles (mostly protons and electrons) spewed by the Sun and provides between 15 minutes and one hour of warning of impending solar blasts. Strong, fast CMEs can spark powerful geomagnetic storms that can cripple satellites, threaten astronauts, induce currents in oil and gas pipelines, or damage poorly protected power grids. They also make for breathtaking auroras that can reach as far south as Alabama, Texas, and even Florida on the rarest occasions.

NOAA

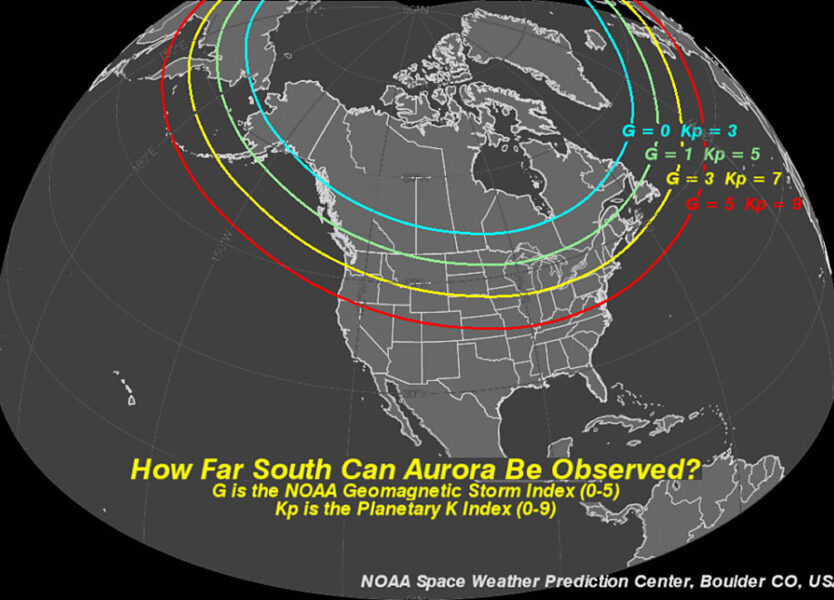

Forecasters at the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) utilize near-real-time data from satellites (including DSCOVR) and ground-based magnetometers that measure fluctuations in Earth's magnetic field caused by solar outbursts. They also factor in the 27-day pattern of coronal hole activity and past solar behavior to generate 3-day and 27-day space weather forecasts. The 3-day outlook is updated every 12 hours and lists the Kp index at 3-hour time intervals. Kp is a measure of geomagnetic activity in Earth's atmosphere on a scale from 0 (extremely low) to 9 (severe geomagnetic storm).

Courtesy of NASA

For observers in the northern border states, a minimum of Kp 4 is necessary to see an aurora, which will typically show as a faint, pale arc ~5° high in the northern sky. The higher the Kp, the brighter, more extensive, and active the display. If you travel to Churchill, Manitoba, on Hudson Bay, the threshold can be as low as Kp1! Conversely, the father south you travel, the higher the index must be for the aurora to come knocking. To get the latest Kp numbers subscribe to NOAA's free forecasts and other alerts.

NOAA

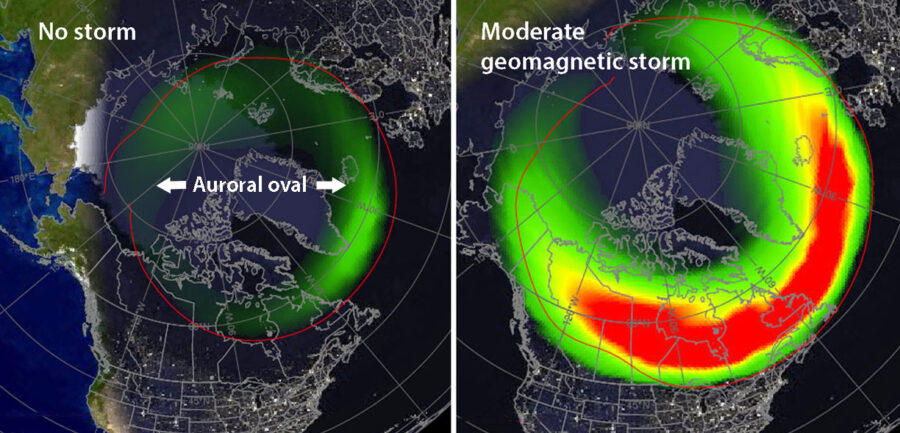

Like the Ring of Fire of heightened seismic activity around the edges of the Pacific Ocean, rings of auroral "fire" are centered on Earth's geomagnetic poles. Normally, blasts from the Sun pass the planet by, deflected by the magnetosphere, the region of space around Earth dominated by its magnetic field. During quiet times, the ovals shrink back, with auroras only visible from under or very near the ring. When a solar squall arrives, the oval expands southward over more populous regions such as the U.S. and the British Isles. Typically, the ring reaches its greatest southward extent around local midnight, the reason the mid-latitude aurora is often most active around that time.

Aurora-making is all about magnetic reconnection. Whenever a chunk of the Sun comes flying our way it's embedded with the solar magnetic field, also known as the Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF) since it spreads across the solar system. If the field of the plasma blast points southward — opposite the direction of the Earth's northward-pointing magnetic field — the two opposing fields reconnect. This happens first on the sunward side of the planet and a second time on the night side (see video above). Reconnection converts the energy stored magnetic fields into heat and kinetic energy that accelerate both in-situ magnetospheric electrons and solar electrons along Earth magnetic fields lines directly into the upper atmosphere. Like an old TV picture tube where a beam of electrons strikes a phosphor layer to create an image, electrons streaming into the polar regions excite the air to glow.

Bob King

Traveling up to 72 million kilometers per hour, the particles slam violently into neutral atoms of nitrogen and oxygen. As the atoms return to their natural rest states, they emit bazillions of red and green photons, painting the sky with light. Excited oxygen produces the aurora's greens and reds, while nitrogen emits a faint, purple-blue hue at high altitudes. During strong storms, molecular nitrogen at lower altitudes emits both red and blue light, which tints the bottom of auroral arcs purple. A camera records all auroral colors far better than the human eye because it can accumulate faint photons during time exposures while our eyes see in real time and take what they get.

NOAA

Space weather forecasters can only speculate about the magnetic field direction of the massive cloud of electrons and protons prior to its arrival at DSCOVR, one of the reasons the best forecasts sometimes miss the mark until shortly before a CME arrives. A big blow might be on the way but fail to connect. Other times, forecasts will predict quiet conditions only for a sudden storm to appear. Crucially, DSCOVR can measure the strength of the solar wind's magnetic field in the north-south direction, a number called the Bz (B sub z). A negative Bz means the field points south and is likely to set its hooks in the magnetosphere. If positive (north), this is unlikely to happen.

NASA / Nick Arge

To keep track of Earth's magnetospheric ups and downs and ensure you're prepared for the next aurora, follow these steps:

- Location. Find a location with a wide-open, minimally light-polluted view of the northern sky. Scout for sites in the daytime, so you're ready to go at night. Keep the Moon's phase in mind. A gibbous or full moon will wash out most displays.

- Check the forecast. Check the 3-day forecast regularly or subscribe to the email service. If the Kp indices indicate a G1 or greater storm for your region, proceed to Step 3.

- Real-time Bz. The topmost graph (in red) at the DSCOVR Real Time Solar Wind site displays the real-time Bz readout. When it dips to –5 or lower — especially if it's below –10 — there's a good chance auroras will be visible for observers in the northern states. If it reads –20 or lower, a much larger portion of the U.S. may see the show. You can check the current Bz value here, too.

- Oval forecast. At the Aurora – 30 minute Forecast site you can view the predicted extent of the northern and southern auroral ovals. If the oval extends to where you live, get your coat on!

- Facebook groups. Check out the Great Lakes Aurora Hunters Facebook page. Members are vigilant at all hours and post frequently.

- Patience. Once you've arrived at your observing site, you may only see a low bow across the bottom of the northern sky. If the arc slowly rises and brightens in the next half-hour to 45 minutes — especially if the Bz is pinned below –10 or –20 — stick around. Chances are it will morph into dancing rays and multiple bows. But if the arc slowly sinks and fades, you may want to call it quits.

- Get an app. Download one of the free aurora apps for your phone. Some send an alert when the aurora is imminent. I have an iPhone and use My Aurora Forecast and Alerts (there's also an Android version) and Aurora Forecast.

NOAA

Remember to take all forecasts with a pinch of salt. Nature has a penchant for setting its own schedule as well as resisting complete explanation. Despite failed forecasts and clouds at just the wrong time I always remind myself there is no reward without disappointment. If you live in the southern U.S. where northern lights are rare, consider booking Sky & Telescope's aurora tour to Iceland. You can also travel to Fairbanks, Alaska, or Norway. You won't regret it. A grand auroral display is as deeply moving as a total solar eclipse, plus it lasts longer!

Read on other celestial events to enjoy this month in the March issue of Sky & Telescope magazine.

10

10

Comments

Graham-Wolf

March 2, 2023 at 6:31 am

Excellent and timely Aurora article, Bob! Here in Otago, New Zealand, (Latitude 46 South) we have been treated to strong displays of the "Aurora Australis" (Southern Lights) all week!! Bright red and bluish rays/pillars to the South West. In the deep twilight, it looked rather like a lingering sunset. Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF), pulling alongside a bright red Mars, low in the N.W. in evening twilight, was a stunning sight to see in 20x80 Binoculars on Feb 11th. Graham Wolf, at Dunedin, NZ>

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 2, 2023 at 10:59 am

Hi Graham,

Thank you! Aurora all week "down South?" Wow! Sounds wonderful. We've had two good displays here at 46.7 North in the past few weeks. Interesting to know that red rays have been as prominent in the aurora australis as they were in our borealis version.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

gmk

March 2, 2023 at 11:21 pm

Great article Bob, it covers a lot of ground. One minor correction:

The right endpoint of Monthly Values on the Solar Cycle Sunspot Number Progression graph is labelled as "Feb. 2023"; I believe it is actually the value for Dec 2022.

The sunspot number for Jan 2023 is now available at https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/solar-cycle-progression, and the above-expectation trend continues.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 3, 2023 at 12:05 am

Dear gmk,

Thank you very much. You are correct! Thanks for pointing out the error. Now corrected 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

SNH

March 3, 2023 at 6:03 pm

EXCELLENT article, Bob. Definitely going to "bookmark" this article! I'm all aboard and now waiting for that storm of Kp 7 or higher.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 4, 2023 at 12:30 am

Hi Scott,

Thank you! I really hope you get the chance to see it. If not, make a trip north sometime in the spring or fall.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

March 3, 2023 at 6:38 pm

How dark does the sky need to be to see an aurora? Any chance in a city with a limiting visual magnitude around 3 or 4?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 4, 2023 at 12:29 am

Hi Anthony,

That's a great question. The most important part is how dark the northern sky must be since that's where most of the action takes place. If the northern sky limiting magnitude is 4, you should definitely see a G3 storm (Kp=7) and probably the brightest parts of a G2 storm (Kp=6).

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

March 4, 2023 at 3:03 pm

Thanks Bob. I'm out of luck, at least here in San Francisco. On an exceptionally clear night I can see fourth magnitude stars within 30 or 40 degrees of the zenith. The horizon in every direction is soup.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 5, 2023 at 10:44 am

Anthony,

Those are tough circumstances. Your best choice is to try an aurora tour in Fairbanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.