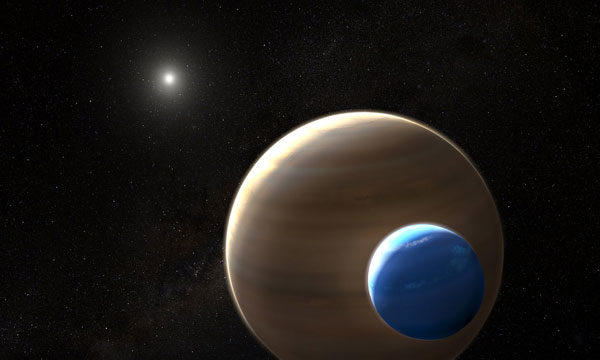

Have astronomers detected two giant exomoons? The answer depends on how convincing you deem these new results — and how you define a moon.

NASA / ESA / L. Hustak (STScI)

More than 4,000 exoplanets have been confirmed since 1995, ranging in size from Earth-size rocks to gas giants, but so far, not one has a moon. Even the tentative detection of a Neptune-size exomoon by Alex Teachey and David Kipping (both at Columbia University) remains hotly debated — new results show it may well be a data reduction artifact.

Now, Cecilia Lazzoni (University of Padova, Italy) says she may have found two giant exomoons in data collected by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. But it’s unclear whether we should call these objects moons – or if they exist at all. At the 4th Extreme Solar Systems conference in Reykjavik, Iceland, where Lazzoni presented her preliminary results on August 19th, she said that the potential planet-moon discoveries could also be described as binary planets.

Lazzoni and her colleagues have analyzed a three-year span of data from the VLT’s Spectra-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet Research instrument (SPHERE), currently the best facility available for directly imaging faint, low-mass companions of stars. In two cases, the analysis turned up faint objects that appeared to orbit the substellar companions.

In the first case, the companion itself is most likely 10 or 11 times more massive than Jupiter, and orbits its red dwarf parent star at a distance of at least 300 to 330 astronomical units (a.u., the average distance between Earth and the Sun) — some 10 times the distance between our own Sun and the planet Neptune. The planet’s “moon” weighs in at just less than Jupiter’s mass, as deduced from its infrared brightness, and has an orbital radius of about 10 a.u.

In the second case, an object with 13 or 14 times Jupiter’s mass orbits at more than 270 a.u. from its Sun-like star. Its “moon” has 4.6 times Jupiter’s mass, and orbits its planet at a distance of 8 a.u. Since the team is collecting more observations as they prepare to submit a scientific publication, Lazzoni hasn’t yet revealed the identity of the two parent stars.

Both in mass and in orbital characteristics, these objects are unlike any planetary satellites in our own solar system. It’s not even clear if they really orbit planets; their hosts are more likely brown dwarfs, objects massive enough to ignite deuterium fusion, but not massive enough to maintain hydrogen fusion in their cores. The dividing line between massive planet and brown dwarf is generally considered to be 13 Jupiter masses, but the line’s a bit fuzzy.

In any case, says Lazzoni, “these would be the first triple systems with two substellar companions.” The discovery could shed light on the formation of brown dwarfs around stars. If planet-size “moons” circle the brown dwarfs on wide orbits, then the brown dwarfs probably formed more like stars than like planets. That is, they were probably born via gravitational instabilities in the cloud of gas and dust from which the central star formed, rather than forming in the circumstellar disk via core accretion.

Eric Nielsen (Stanford University), who studies directly imaged giant planets and brown dwarfs with the Gemini Planet Imager on the Gemini South Telescope in Chile, says he’s “intrigued” by the result. But, he adds, “these are extremely difficult techniques, so we really need independent confirmation.”

Meanwhile, on his Twitter account, exomoon hunter Teachey says the classification of the candidate objects may have to depend on the formation history of their parent bodies: “If a brown dwarf is just a really massive Jupiter, then they’re moons! (if they exist)”

Editorial note: Some additions and modifications were made to this post on August 30, 2019.

3

3

Comments

Robert-Casey

August 29, 2019 at 6:10 pm

If these "exomoons" are around a Jupiter mass and orbit their parent planets at many AU, then it should be likely that the exomoons have moons of their own, maybe "subexomoon"? They'd be way beyond detectable though.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ken-Winters

August 29, 2019 at 11:39 pm

By current methods yes, but 5 or 10 years from now? Who knows.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

August 30, 2019 at 1:25 pm

There are stability issues with that scenario. I know of no moons-around-moons in the solar system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.