Gravitational-wave detectors should be able to locate a population of huge black holes soon. A new study predicts when we’ll find them, and what they’ll teach us.

SXS Lensing

Theory predicts that gravitational-wave detectors should be able to observe a population of huge black holes. A new study explores what we’ll learn from these mysterious objects and when we can hope to find them.

A Preferred Size

LIGO-Virgo / Northwestern U. / Frank Elavsky & Aaron Geller

So-called stellar-mass black holes — the black holes probed by gravitational-wave detectors like LIGO/Virgo — can theoretically span a broad range of sizes, from just a few solar masses to hundreds of times the mass of the Sun.

The LIGO/Virgo gravitational-wave detectors have discovered signals from dozens of black-hole binaries completing their final death spirals and merging. So far, these observed primary black holes have primarily fallen into a mass range below ~45 solar masses, indicating a precipitous drop in the population of binary black holes above this mass.

Avoiding an Unstable End

ESO / M. Kornmesser

Why the dearth of heavier black holes? Theorists have an explanation: the pair-instability supernova mass gap. Based on our understanding of stellar evolution, black holes in a certain mass range — roughly 50–120 solar masses — shouldn’t be able to form. This mass gap arises because the progenitor stars needed to produce black holes of this size are predicted to undergo a runaway process, eventually exploding as violent supernovae that prevent remnant black holes from forming.

The formation of black holes above ~120 solar masses, however, should still be possible — so we’d expect a population of enormous far-side-of-the-mass-gap black holes to be lurking in our galaxy and beyond. In a new study, University of Chicago scientists Jose María Ezquiaga and Daniel Holz dig further into this prediction.

Hunt on the Far Side

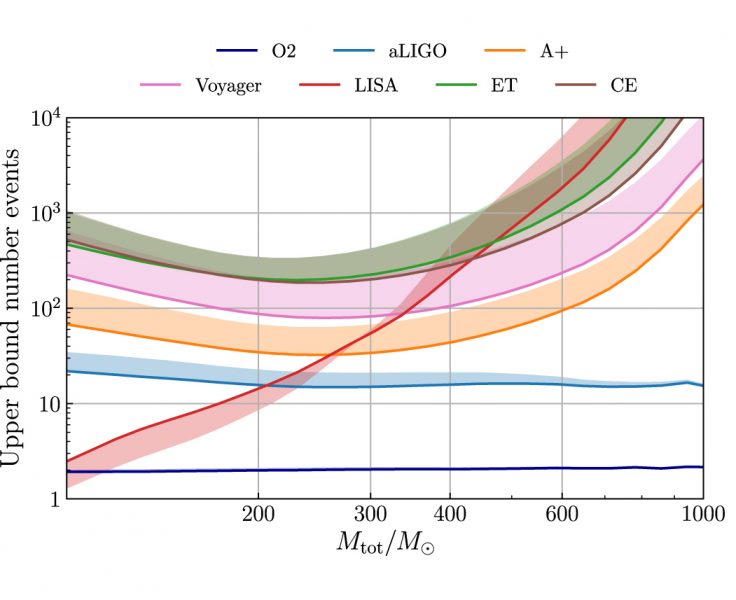

Ezquiaga and Holz use the statistics of past black-hole binary detections and predictions of the capabilities of current and future gravitational-wave detectors to estimate what’s in store for us in terms of far-side black holes.

First, the authors show that these heavyweights would be the most massive sources detectable by LIGO/Virgo, and — if they exist — we should be able to spot up to tens of them during LIGO/Virgo’s next two observing runs (O4 and O5).

Adapted from Ezquiaga & Holz 2021

What’s more, far-side binaries should also lie in the observing band of LISA, the upcoming space-based gravitational-wave mission. They may dominate the population of binaries that can be observed by both LIGO/Virgo and LISA, providing valuable information about how the merger rate for black-hole binaries changes over time.

Finally, Ezquiaga and Holz show that observations of far-side binaries with LISA, LIGO/Virgo, and the Einstein Telescope (a next-generation detector) will provide an independent measure of the expansion of the universe at different redshifts: z ~ 0.4, 0.8, and 1.5, respectively. By exploiting the upper edge of the mass gap, far-side black holes can act as standard sirens and enable precision cosmology.

Soon To Be Found?

So what’s the upshot? The outlook is good for far-side black holes!

If these heavyweights exist, we should spot them within the next couple years and they’ll be able to provide us with valuable insight into a variety of science questions. If we don’t observe any within this time frame, that also provides a powerful statement about black-hole formation, demanding new theories to explain the dearth.

Citation

“Jumping the Gap: Searching for LIGO’s Biggest Black Holes,” Jose María Ezquiaga and Daniel E. Holz 2021 ApJL 909 L23. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abe638

This post originally appeared on AAS Nova, which features research highlights from the journals of the American Astronomical Society.

9

9

Comments

Ransom

May 22, 2021 at 11:12 am

"black holes in a certain mass range — roughly 50–120 solar masses — shouldn’t be able to form" and yet the Masses in the Stellar Graveyard chart shows several in this mass range. What's the explanation?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

May 22, 2021 at 7:42 pm

Mergers, perhaps?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thomas Haas

May 22, 2021 at 3:36 pm

I seem to remember that one of the first black hole mergers detected by LIGO and its ilk consisted of a hole with, say, 20 solar masses and one with 40, resulting in a combined hole with ~ 57 solar masses and 3 in the form of gravitational radiation. Whatever happened to "nothing ever comes out of a black hole" ??? THREE solar masses 'evaporated' ???

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

May 22, 2021 at 7:40 pm

Easy. Where do you think the energy comes from to create the gravitational wave? Also what happens to any the material outside the event horizons? You'll find the answers there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thomas Haas

May 23, 2021 at 3:50 pm

so what you are saying is that only matter inside the event horizon cannot "come out" ??

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

May 23, 2021 at 6:55 pm

Yes. Read this excellent Forbes articlethat will answer your questions nicely.[1]. Hope this helps.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thomas Haas

May 24, 2021 at 1:45 am

Light at last ! This finally makes sense to a poor chemist (who needs to know about elements and binding energy but simply accepted the fact and never bothered to ask where it came from....)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

May 24, 2021 at 5:09 am

Excellent, as I was looking for such an impact for you to discover youself. This is a common misunderstood question, so sorry for my teasing poses. The impresses the power of General Relativity, which predicts both the existence of gravity waves and their expected signatures during black hole mergers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tony1951

November 11, 2021 at 1:22 pm

I'm considerably puzzled by the phenomenon of Black Holes. They appear to be super massive objects which have collapsed in on themselves, shrinking to tiny dimensions considering their enormous mass. My problem is that I don't understand why they don't on collapsing, turn into colossal supernovae. After all, isn't a supernova simply a star whose mass exceeds its ability to stay inflated and simply, on collapsing, changes its fusion mode to an almost instantaneous release of vast fusion energy? If black holes can collapse into immensely dense objects and even come together and combine, why don't they do the supernova thing?

Thanks for any solutions to this - or attempts at them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.