New research shows that our quiet, middle-aged galaxy used to be quite the firecracker — a couple billion years ago it was making new stars at 10 times the rate it is today.

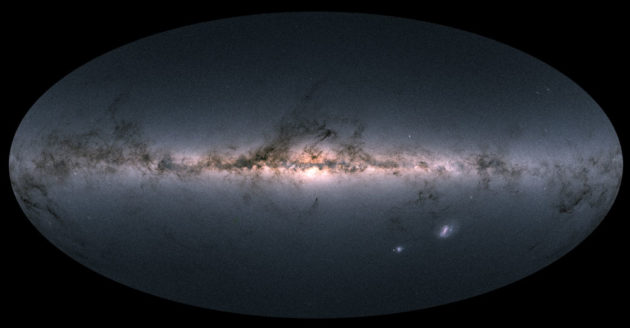

The Milky Way is pretty sedate as galaxies go. It makes just a Sun’s worth of stars a year, when starburst galaxies may manufacture hundreds or thousands of times that rate. But the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite is providing a window into our galaxy’s past, which shows a very different view: Just a couple billions of years ago, something ignited a stellar firestorm in our galaxy.

Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC) / A. Moitinho / A. F. Silva / M. Barros / C. Barata (Univ. of Lisbon, Portugal) / H. Savietto (Fork Research, Portugal)

The Gaia mission released a transformative catalog just over a year ago, recording precise distance and motion measurements for more than a billion stars in our galaxy. Now, Roger Mor (University of Barcelona, Spain) and colleagues are using that exquisite data set, along with some sophisticated computer algorithms, to delve into the Milky Way’s past. Their results appear in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The researchers select the apparent brightness, color, and distance for 2.9 million stars in the Gaia catalog. They then feed this information into a simulation, which reconstructs both the initial stellar masses — that is, counting out how many small stars formed relative to the few very massive ones — and the way those stars are distributed in the galaxy.

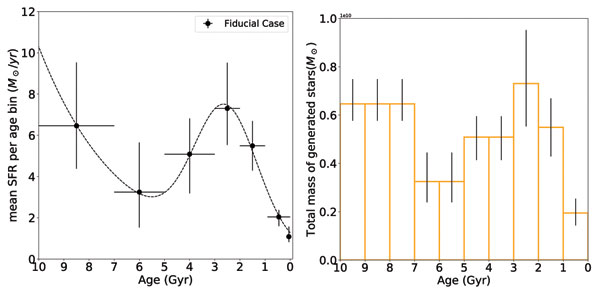

By understanding how the stars formed and where they are now, the simulation can recreate the galaxy’s star formation history. The results are intriguing: About 10 billion years ago, our young galaxy was making stars by the dozens. But its manufacturing rate was in steady decline for the next 5 billion years. Indeed, previous studies have suggested that the Milky Way swallowed a Small Magellanic Cloud-size galaxy, dubbed Gaia-Enceladus, more than 10 billion years ago. That merger might have stimulated a rush of star formation before eventually quashing it.

Axel Mellinger / Central Michigan University

Then, 5 billion years ago, or perhaps even earlier, another event ignited a stellar baby boom. The proliferation of new stars lasted some 4 billion years. Perhaps, the authors speculate, the Milky Way had collided again, this time with a gas-rich satellite galaxy. That would explain the long boom, which peaked 1 or 2 billion years after it started, when stars were forming at 10 times today's rate. Ultimately, the galaxy churned out enough stars to populate half of its thin disk. In other words, our galaxy would appear vastly different (and smaller) without this recent merger.

The rate of new stars has been diminishing ever since. The research team’s simulation ends with the present-day Milky Way making only a solar-mass worth of stars a year, in agreement with other measurements.

Roger Mor et al. / Astronomy & Astrophysics 2019

The likelihood of such a recent encounter finds support in cosmological simulations, which suggest that a Milky Way-like galaxy has a high probability of swallowing up another galaxy within the last 10 billion years. For the more observationally minded, there’s also a growing pile of studies that have been finding a sudden ramp-up in star formation 2–3 billion years ago.

If the Milky Way really did engulf its companion galaxy a couple billion years ago, one thing’s for sure — our night sky wouldn’t be the same without it.

Editor's note: This post was updated on May 22, 2019, to add a plot showing how our galaxy's star formation history has changed over time.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.