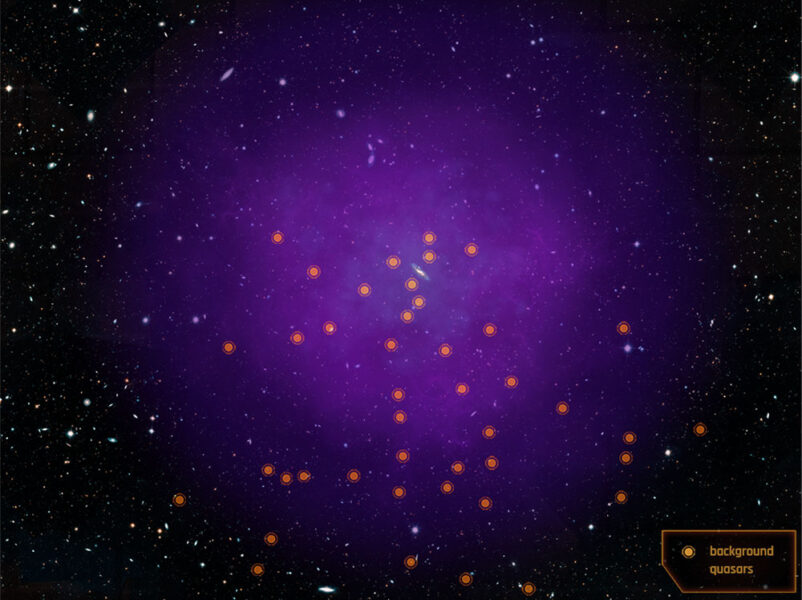

Astronomers have observed 43 quasars in back of our sister galaxy, Andromeda, using the distant beacons to map its halo of hot gas.

If it’s clear tonight, you might go outside and find the Andromeda Galaxy between the Cassiopeia and Andromeda constellations. Our galactic sibling is currently 2.2 million light-years away, so it appears as a spindle-shape bit of fuzz that requires dark skies to see. A few billion years from now, our descendants will have an even better view, as we’re headed almost straight for it.

Even today, though, new observations show the two galaxies are already “touching.” New research on the hot gas surrounding Andromeda shows that it’s likely already overlapping the Milky Way’s halo.

NASA / ESA / E. Wheatley (STScI)

Hot Gas Hiding in Plain Sight

Every large galaxy is surrounded by gas so hot (between 10,000 and 100,000 degrees) that it hasn’t settled yet. But this gas is hard to see — it doesn’t emit much light itself, so astronomers see it mostly as part of foreground “clouds” that absorb light from background sources.

In the September 1st Astrophysical Journal (preprint available here), Nicolas Lehner (University of Notre Dame) and colleagues used an unprecedented number of such background sources to map the hot halo around Andromeda.

Quasars are the bright centers of galaxies, where black holes devour gas — they’re luminous enough to shine from the earliest ages of the universe. Nevertheless, they’re points of light, and most foreground galaxies are quite small on the sky. So, despite the trillions of galaxies in our cosmos, there aren’t typically a lot of quasars in back of any one galaxy — maybe one or two.

But Andromeda is close enough — and therefore appears large enough — that Lehner and colleagues identified and observed 43 distant quasars near it on the sky. (This study extends previous research by the same team using 18 quasars.) Using the Hubble Space Telescope, the researchers measured spectra of these background quasars, essentially taking 43 different “core samples” through the halo to map out its structure.

Andromeda is a big ‘un and has had its share of galactic scrapes. So it’s not surprising that its halo is a jumbled mess. But with the new map, Lehner’s team sees the halo essentially has two distinct regions: a disturbed inner shell and a smoother outer section. The outer section represents gas leftover from the galaxy’s formation; the inner shell has been stirred up in the more recent past, likely by supernovae in the galaxy’s disk.

A Common Halo

The team also found that the halo is huge — it extends almost 2 million light-years from the galaxy’s center. If we could see it, it would be three times the width of the Big Dipper!

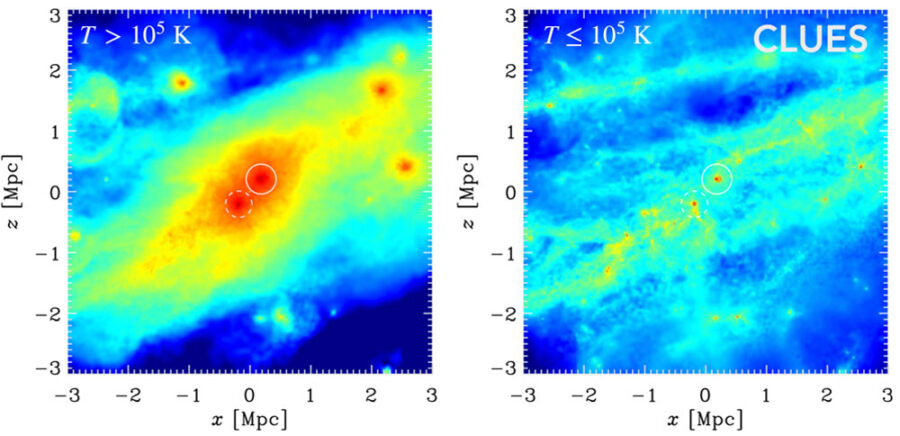

If the Milky Way’s halo has a similar size, and there’s no reason to think it shouldn’t, then the two halos actually overlap in space. That’s not to say that their collision has begun: The halo gas is so spread out, and the relative velocities so low, that the gas doesn’t collide per se. Instead, the Milky Way and Andromeda might share a common halo, as shown in simulations.

Nuza et al. 2014 / Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

“Unfortunately, in the real world, we will not be able to see that and likely not even determine independently the true scale of the halo of the Milky Way,” Lehner says. The observations are simply too difficult to obtain.

Still, the idea that our galaxy and its galactic sister are connecting across millions of light-years is something fun to think about as you look up at that fuzzy oval in the sky.

1

1

Comments

Yaron Sheffer

September 19, 2020 at 6:56 pm

The AG is about 2 million light years away, so a halo extending about 2 million light years from its center would subtend about 45 degrees in our sky. But this is just the radius. The full halo diameter would amount to about 90 degrees, with an area occupying roughly a whole quarter of our entire sky!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.