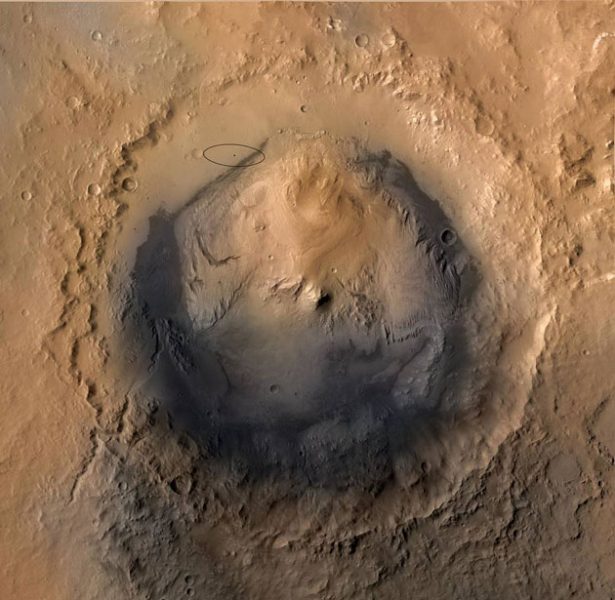

New measurements from NASA’s Curiosity rover show that methane concentrations near the Martian surface vary on a daily cycle. The finding could help reconcile conflicting data.

Researchers already suspected it, but now they have proof. The concentration of methane above Gale Crater, the landing site of the Curiosity rover, changes from day to night. It goes from low but measurable levels during the night to concentrations near zero during the day. That daily cycle may help explain why different instruments were seeing, and not seeing, methane.

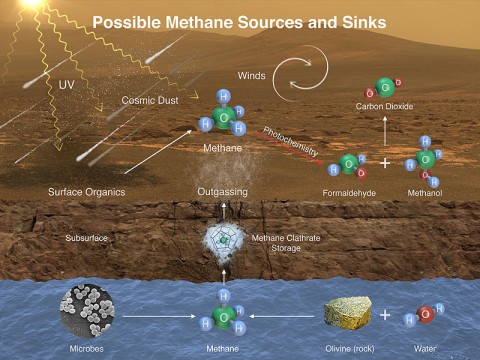

Scientists have spent decades chasing methane on Mars. On Earth, the gas can be a sign of microbial activity, but it can also be a product of chemical reactions between liquid water and certain minerals. Finding methane in the Martian atmosphere could reveal that similar processes are occurring underground on the Red Planet.

Curiosity first sniffed methane on Mars on June 15, 2013. Since then it has found that background levels vary between 0.2 and 0.7 parts per billion in volume (ppbv). Subsequent measurements suggest that methane abundances might follow a seasonal pattern, with more of the gas present during the summer and less in the winter (although a recent statistical analysis says that interpretation may not be statistically sound).

Curiosity also detected occasional peaks in methane concentration, known as plumes, which reached a maximum of 20.5 ppbv on June 19, 2020. In 2013, one of these plumes was detected simultaneously by Curiosity and the European Space Agency (ESA) Mars Express orbiter.

Scientists speculate that methane could be leaking from the Martian underground, where it’s either generated by ongoing processes or stored in reservoirs formed in the distant past. Alternatively, the gas might form on the surface when solar ultraviolet radiation breaks up meteoritic dust that falls onto the planet from outer space.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SAM-GSFC / Univ. of Michigan

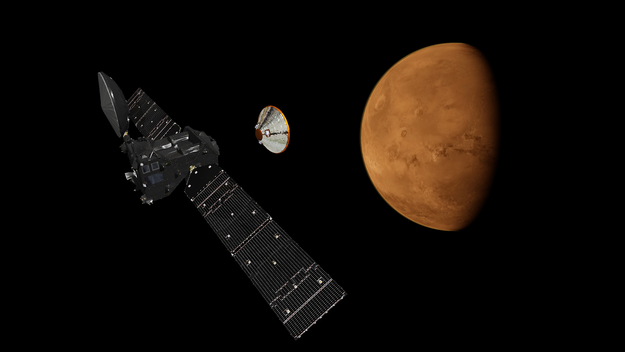

But in April 2019, the ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, a spacecraft specifically designed to measure vanishingly small concentrations of gases in the Martian atmosphere, failed to find signs of methane after several months of operation. A collaborative project between ESA and Roscosmos, TGO looks at sunlight as it travels through the upper layers of the atmosphere, five kilometers above the ground, and should be able to detect particle concentrations as low as 0.05 ppbv. That’s 10 times less than what was being routinely measured by Curiosity.

After months of heated debate, a group of researchers led by John Moores (York University, Canada), realized that the discrepancy could boil down to the time of day the measurements were taken. “What if they’re both right, what does that tell us about Mars?” Moores wondered. “Then you’ve got to have methane changing over the course of the day.”

Curiosity’s chemistry lab is a power hog. Every time it does a methane run, the Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) inside the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) pumps in Martian air for several hours. For that reason, those runs have always been done at night, when no other instruments are operating. The Martian atmosphere is cool and calm at night, Moores noted, making it more likely that it will hold onto any molecules slipping out from an underground source. But while Curiosity was able to detect the methane at the surface, the TGO was looking at the atmosphere at sunset, after an entire day of Sun-driven atmospheric mixing, when the methane could already be too diluted to pick up.

ESA/ATG medialab

To test the idea, the Curiosity team attempted a couple of methane runs during the day. TLS bracketed one nighttime measurement with two daytime ones. The nighttime measurement yielded 0.52 ppbv, in line with previous results, while the two daytime measurements picked up no methane at all, confirming Moores’s prediction.

“We are sure that the ground in Gale crater is leaking methane, even at the low levels observed,” says Chris Webster (Jet Propulsion Laboratory), principal investigator of the TLS instrument. “Our new data take an important step toward reconciling the Curiosity and ExoMars data sets.” Webster and his team reported these results in the June Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Even if they are right, though, the rate of methane seeping from underground reservoirs into the atmosphere must be very low. Moores and his colleagues estimated that a maximum of 2.8 kilograms of methane escaping from Gale Crater every day could explain Curiosity’s measurements without increasing global levels above TGO’s 0.05 ppbv detection limit.

Then again, it’s very unlikely that Gale Crater is the only place on Mars that leaks methane. If all the similar craters on Mars spewed methane at the same rate, the gas would over time build up to levels TGO could detect. Methane molecules should survive for an average of 300 years in the Martian atmosphere before solar radiation tears it apart, but TGO’s nondetection suggests something else is going on. “Methane would have to be destroyed much more rapidly,” Moore says.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / ESA / DLR / FU Berlin / MSSS

Experiments are underway in several labs on Earth to determine what could be destroying methane. One possibility is that small electrical discharges between suspended dust grains could be responsible. Another possibility is that the gas is reacting with the oxygen-rich Martian surface in ways not predicted by current photochemical models. Maybe methane is just getting stuck to the dust floating in the atmosphere.

Moores thinks we need more measurements from the ground. Curiosity has made about 16 measurements in a decade. “It's a very coarse data set and you can imagine that it must be difficult to figure out what happens over the day if you only measure every six months.”

“Neither the Perseverance or Chinese rovers are able to measure Mars methane at any level,” Webster says. He suggests that a mini-TLS, either launched on an independent mission or piggybacking on a planned future mission, could identify how much and how often methane is released to help settle its source.

2

2

Comments

Robert-McCabe

July 7, 2021 at 10:01 am

"Another possibility is that the gas is reacting with the oxygen-rich Martian surface in ways not predicted by current photochemical models."

Oxygen-rich surface?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

July 7, 2021 at 3:16 pm

The surface of Mars has a lot of perchlorate salts. Cl O4 (-) . Perchlorate is highly reactive -- it's used as an oxidant in rocket fuel. Iron oxide gives Mars its rusty color.

https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/salts-on-mars-are-a-mixed-blessing

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.