We explore Comet ZTF’s remarkable trio of tails and share the latest news and photos.

Dario Giannobile

With the Moon approaching full phase, this is a good time to check in on the comet of the hour, Comet ZTF (C/2022 E3). Currently glowing around magnitude 5.0 it's already exceeded the more pessimistic brightness forecasts. On January 28th from my home under moderately dark skies (SQM of 21 — Bortle 4) I easily spotted the interloper without optical aid as a 20′-wide, fuzzy glow with a brighter center 5° northwest of Kochab in the Ursa Minor. Despite being magnitude 4.8, it wasn't obvious to the eye unless you knew exactly where to look. Three mornings later I saw it at magnitude 5.0.

There's been intense interest public interest in the comet due to heavy coverage in the news and social media. Everyone wants to see the "green comet." A crowd of people joined me on January 26th for a look through my 10-inch telescope as the temperature hovered around 0° F (–18°C). Although moonlight and light pollution whittled it down to just a coma and bright core, no one left disappointed. Sometimes you don't need a lot of fanfare and rah-rah. The simple "is-ness" of nature is enough. There's also no denying that people like seeing what everyone's been talking about.

Dan Bartlett

Peak brightness is expected on February 1st. That's also when Comet ZTF will pass closest to Earth (42 million km) and the last time we'll see it in a moonless sky until February 7th. When that day arrives, the comet should be a 6th-magnitude object zipping across Auriga at the rate of 4° per day. As it recedes from Earth its pace soon slows. Despite a bright Moon in the coming nights, I encourage you to keep watching, as the comet makes scenic passes of Capella on February 5th and Zeta (ζ) Aurigae on February 6th. Given its bright, compact nuclear region I suspect it will remain visible in 50-mm binoculars and small scopes. It's also anchored in the evening sky, making observation more convenient.

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

Don't forget to check the night of February 10–11. That's when this flying iceberg passes within 1° of Mars. Skywatchers in the Southern Hemisphere have been eager to get their first looks at this (so-far) northern comet and will get their chance beginning around February 4th. Amateurs know exactly how it feels to wait for an exciting southern object to come north, so we're happy to share the bounty. To find Comet ZTF you can use the chart above, check out the Sky & Telescope version, or easily create your own at in-the-sky.org by clicking in the Object field, typing C/2022 E3 (ZTF), and pressing Update.

NASA, JPL-Caltech

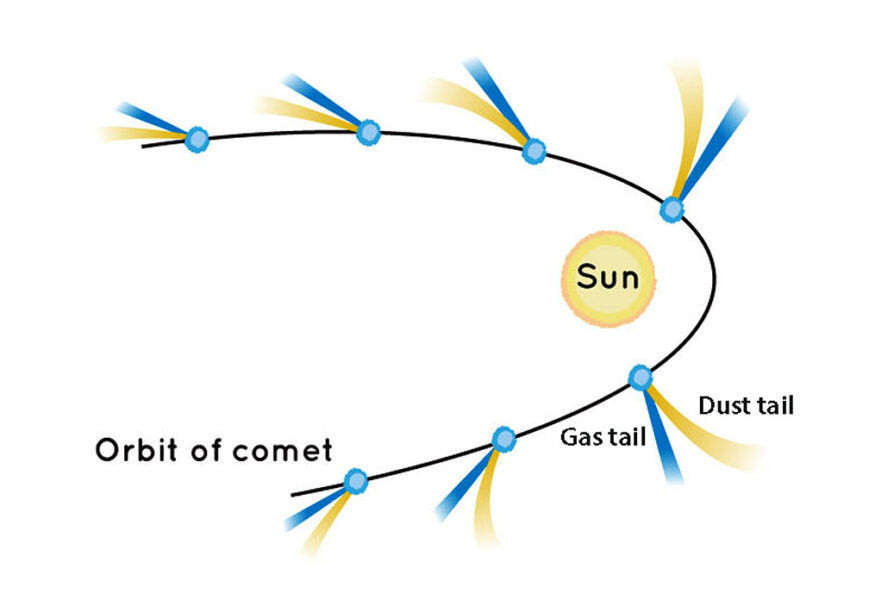

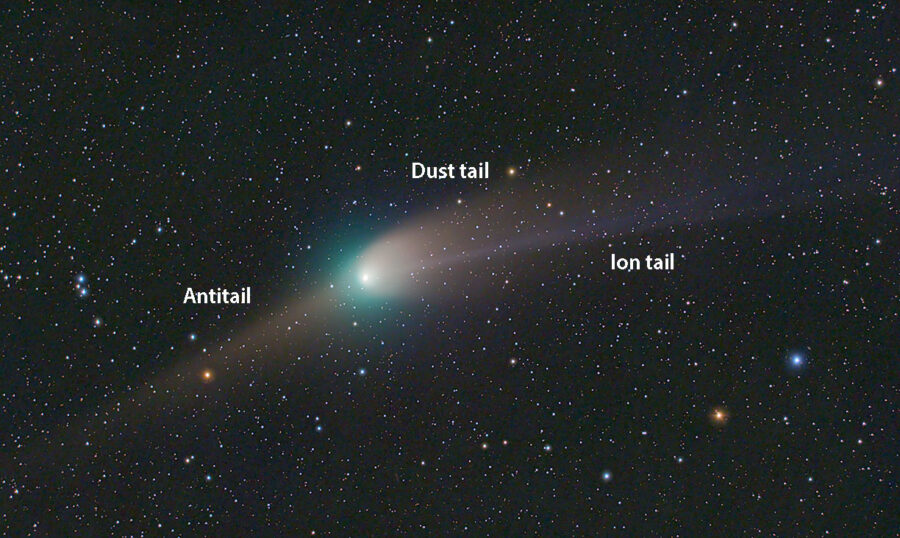

Comets often sprout multiple tails. Heat from the Sun vaporizes their dust-rich ices, propelling gas and dust into space around the nucleus to form a temporary atmosphere or coma. Comets are also small, typically just a few kilometers across. With little gravity to hold onto much of anything, the radiation pressure of sunlight pushes the lofted debris behind the comet's head to form a dust or Type II tail. Cometary dust scatters longer wavelengths better than shorter ones, giving dust tails a yellowish or pinkish hue. Comet ZTF's wedge-shaped dust tail glowed distinctly pink in photos but appeared colorless visually.

Left Michael Jaeger (left and right) and Dan Bartlett (center)

At the same time, neutral gases released into the coma are broken apart by solar ultraviolet (UV) light. Water (H2O), for example, cleaves into OH– and H+. Ultraviolet light ionizes other molecules which are carried off by the magnetic force entrained in the solar wind to form a Type I or ion tail. The familiar blue of the ion tail — a hue difficult to detect visually but easily captured on camera — stems from ionized carbon monoxide.

Miguel Claro

An ion tail points directly away from the Sun like a windsock in a gale. For good reason — the solar wind normally blows at around a million miles an hour (400 km/s), much faster than most comets travel. Fluctuations in the wind's speed and magnetic direction produce kinks and knots in the tail and sometimes sever it altogether like a scissors-snip at a ribbon cutting. Neutral dust particles are unaffected by the solar tempest and lag behind in the comet's orbital path to form a curved tail. Very bright comets such as Hale-Bopp (C/1995 O1) and NEOWISE (C/2020 F3) also exhibit faint, narrow tails of neutral sodium atoms directed radially away from the Sun like typical ion tails.

Chris Schur

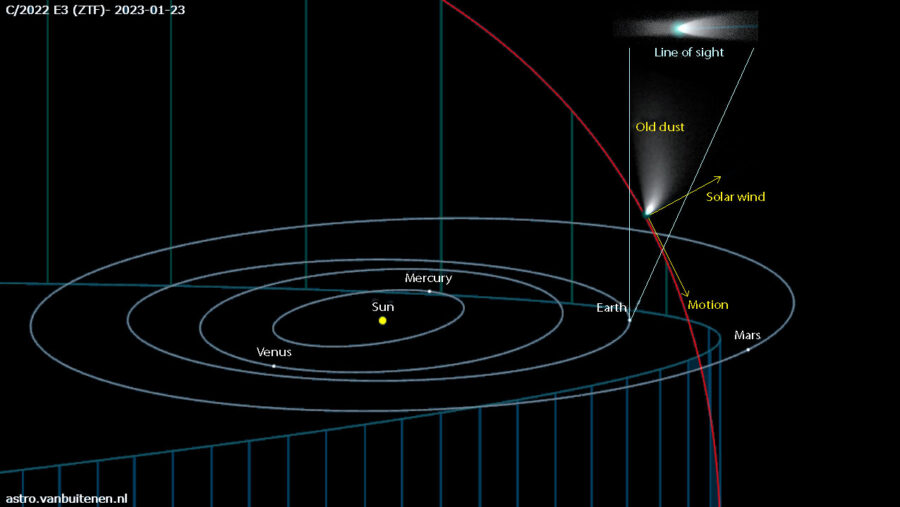

Our viewing perspective affects the appearance of a comet's tail as well. Seen broadside they can appear long and graceful. Head-on views compress and foreshorten them into wedges and spikes. Comet ZTF displayed a foreshortened, fan-shaped dust tail during the late fall and early winter as it passed high above the solar system plane. Later it grew a long, corkscrew ion tail and more recently gifted us a prominent antitail. Antitails are somewhat uncommon and appear in the sunward direction opposite the dust tail. At first glance they seem to defy logic. How can a tail appear ahead of a comet?

Gideon van Buitenen

An antitail is composed of larger dust particles spalled from the comet's nucleus that are less affected by the Sun's radiation pressure and linger behind in the comet's orbital path. If the Earth happens to pass through the comet's orbital plane, we see the dust stack up across our line of sight and form a spike or band sticking out of the coma opposite the dust tail. Similarly, stars stack up across the distance from our vantage point in the galactic disk to create the glorious band of the Milky Way. Because both comet and Earth are always on the move, antitails gradually fan out, fade and disappear, which is exactly what happened with Comet ZTF earlier this week.

Gideon van Buitenen

Its antitail was strikingly obvious for several nights before and after orbital-plane crossing on January 23rd. I saw it easily (though faintly) in 10×50 binoculars on January 26th. By January 31st it was gone. No surprise really since it was little more than an optical illusion albeit a convincing one! The interplay of tail development as viewed from the moving platform of Earth have made Comet ZTF (C/2022 E3) both fun and satisfying to observe. And there's more to come as planet and comet continue their separate ways.

5

5

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

February 1, 2023 at 8:00 pm

Thanks very much Bob. It is fascinating to try to relate all this information to what I see through my binoculars.

Even here in light polluted San Francisco I have been able to see the comet almost every night since January 17. The bright coma has been visible even through moonlight and haze. When the sky has been clear, the Moon below the horizon, and all the neighbors' outdoor lights off, the dust tail has been faintly visible mostly with averted vision. The mornings of January 23 and 24 were very clear and the tail fanned out behind both sides of the coma. That was cool! Since then as the comet has appeared to get bigger it also looks more diffuse, it just fades out into the sky without any distinct edges.

It's been fun to follow this comet for a couple of weeks. I've gotten a little taste of how you comet aficionados get hooked! You don't know exactly what you're going to see from one night to the next. And the fact that I can see this comet for just a few weeks while it passes through the inner solar system during an orbit of tens of thousands of years is humbling and mind-boggling.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

February 2, 2023 at 10:53 am

Anthony,

Nice description of the comet's ever-evolving appearance. And you're so right — we only get a few weeks after a nearly unimaginable amount of time in the coming and going.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ernie Ostuno

February 1, 2023 at 8:50 pm

Finally saw it at 0125 UTC 2/2/23 after a month and a half of cloudy skies. Seems like I've been waiting the 50k years since the last time it came around for the skies to clear here in Michigan. It was close by HD 42818, a 4.75 magnitude star... and almost as bright. Of course I couldn't see any of the tails given the very bright waxing gibbous moon and the light pollution, but I liked reading about them! Excellent info, Bob. The coma is high surface brightness and easy to see in 10x50 binoculars, with a grayish-blue, and maybe very slight greenish color.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

February 2, 2023 at 10:51 am

Hi Ernie,

I appreciate you writing in with a bright moon observation. I chuckled when you described how long you had to wait for clear skies. It was like that at my place too until the veil was finally lifted.

Good luck and enjoy a nice visit with the comet over the coming weeks. And dare I add: Clear skies!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

NS

February 7, 2023 at 1:36 am

I think I finally saw it from my home near Honolulu at about 0600 UTC 2/7/23 (2000 2/6 local time). Just a fuzzy spot, lots of lights around me, the sky is very bright, and there were clouds blowing through. I was trying to see it before the moon rose. I may be able to get out to a darker location this weekend so hopefully I'll see it again under better conditions!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.