The Hubble and Webb Space Telescopes have revealed a bounty of galaxies in a pair of colliding clusters, capturing twinkling lights within.

NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / Jose M. Diego (IFCA) / Jordan C. J. D'Silva (UWA) / Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI) / Jake Summers (ASU) / Rogier Windhorst (ASU) / Haojing Yan (University of Missouri)

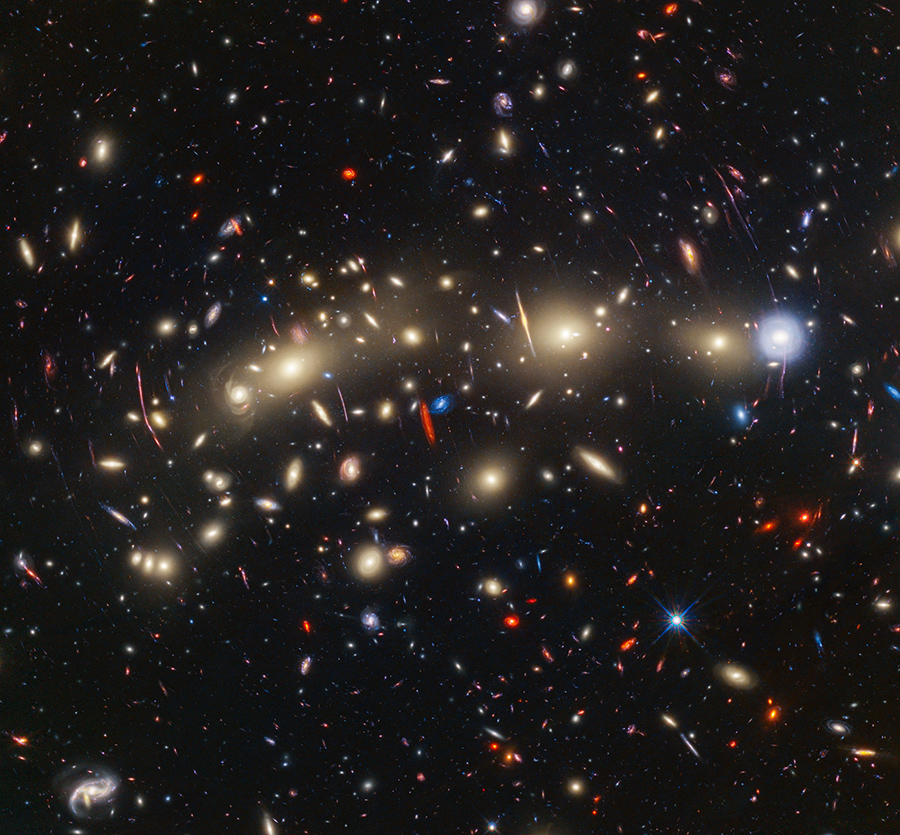

NASA has dubbed this image the "most colorful view of the universe." That's because this deep (long-exposure) image of a distant galaxy cluster combines the light collected by both the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes. Between the two of them, the telescopes cover wavelengths from 400 to 5,000 nanometers.

Those colors can clue us in to the galaxies' distances. The bluest galaxies are relatively nearby, often showing intense star formation, as best detected by Hubble. Redder galaxies tend to be farther away. However, some nearer galaxies may appear red because they contain so much cosmic dust, which absorbs bluer light.

Hubble began observing this galaxy cluster — which is actually two clusters coming together — as part of its Frontier Fields program in 2014. JWST's PEARLS program, short for Prime Extragalactic Areas for Reionization and Lensing Science, is now following up on these fields, imaging them at infrared wavelengths to extend our view back in space and time.

JWST's observations were for more than depth, though; they were spaced so that they could also capture so-called transients, astronomical phenomena that change. Transients may be anything from supernovae and other cosmic explosions to ordinary stars that are briefly gravitationally lensed by a passing foreground object.

Haojing Yan (University of Missouri in Columbia) and colleagues identified 14 transients over a series of JWST images of this field. Two of these are probably supernovae, the rest are likely stars briefly magnified by foreground objects. These results will appear in the Astrophysical Journal Supplements (preprint available here). The sheer number of discoveries from these first PEARLS observations promise many more to come.

NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / Jose M. Diego (IFCA) / Jordan C. J. D'Silva (UWA) / Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI) / Jake Summers (ASU) / Rogier Windhorst (ASU) / Haojing Yan (University of Missouri)

Among the transients the team identified, one stood out, its light shining from 3 billion years after the Big Bang. This monster star system — likely a pair of supergiant stars — is magnified by a factor of at least 4,000, earning it the nickname “Mothra.” (In case you're wondering, yes, there's a previously identified magnified star nicknamed “Godzilla.”)

Mothra is also visible in the Hubble observations that were taken nine years previously, which is odd because the background star and the foreground galaxy cluster ought to have moved enough relative to one another to shift any special alignment between them, nixing the gravitational lensing. The team suggests that an object closer to the star itself, something with a mass between 10,000 and 1 million times the mass of our Sun, is also working to magnify the star. That mass could fit a globular cluster, says Jose Diego (Institute of Physics of Cantabria, Spain), who led a study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. But the exact nature of the object still isn't known.

Read more in NASA's press release.

1

1

Comments

rocketMike

November 11, 2023 at 10:45 am

"That mass could fit a globular cluster, says Jose Diego (Institute of Physics of Cantabria, Spain), who led a study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. But the exact nature of the object still isn't known."

Or might it be an artifact of dark mass/energy playing peek-a-boo with us?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.