Gary Seronik

Maybe you just got a shiny new telescope to call your own. Congratulations — you could be on your way to discovering many stupendous, far away things in the night sky. Although most of them are so far and faint that just locating and detecting them is the challenge! Whether your new scope is a long, sleek tube or a compact marvel of computerized wizardry, surely you're itching to try it out.

Here are three crucial tips for getting started:

First, get your scope all set up indoors. Read the instructions, and get to know how it all works — how it moves, how to change eyepieces, and so on — in warmth and comfort. That way you don't have to figure out unfamiliar knobs, settings, and adjustments outside in the cold and dark.

Second, take the scope outside in the daytime and familiarize yourself with how it works on distant scenes — treetops, buildings — to get a good feel for what it actually does. For instance, you'll find that a telescope's lowest magnification (the eyepiece with the longest focal length) gives the brightest, sharpest, and widest views, with the least amount of the wiggles. The lowest power also makes it easiest to find what you're trying to aim at, thanks to that wide field of view. So you'll always want to start off with the lowest power. Switch to a higher magnification only after you've found your target, got it centered, and had a good first look.

Also, if the telescope has a little finderscope or red-dot pointing device attached to it, daytime is the easiest time to align the finder with the main scope. Aim the telescope at a distant treetop or landmark, center that in the view, and then look through the finderscope. Use the finder's adjustment screws to center the crosshairs (or red dot) on the same treetop. Then recheck that the treetop is still in the center of the main scope's view, to make sure you haven't thrown it off.

Third, be patient. Spend time with each sky object you're able to locate, and really get to know it. Too many first-time telescope users expect Hubble-like brightness and color in the eyepiece — when in fact most astronomical objects are very dim to the human eye. And, our night vision sees almost everything as shades of gray. Much of what the universe has to offer is subtle and, again, extremely far away! But the longer and more carefully you examine something, the more of it you'll gradually discern.

On the other hand, the Moon and the naked-eye planets are bright and easy to find. They make excellent first targets for new telescopic observers. Sky & Telescope's This Week's Sky at a Glance has suggestions for both telescopic and naked-eye viewing of the brightest stars and planets.

Here are some suggestions for starting off.

New-Telescope Delight: The Moon

The Moon is one celestial object that never fails to impress in even the most humble scope. It’s our nearest neighbor in space — big, bright, starkly bleak, and just a quarter million miles away. An amateur telescope and a good Moon map can keep you busy forever.

The Moon tonight (December 25, 2020) is high in the evening sky in its waxing gibbous phase, somewhat thicker and more "bulgy" than in the photo above. In the next few days it will wax further and become full on the 29th.

But the when the Moon is full we see no shadows being cast sideways to dramatize the mountains and craters. You'll always see lunar surface features best along the Moon's terminator, the lunar sunrise or sunset line. (Look again at the photo at the top of this page.) The terminator is where the low Sun in the lunar sky casts long black shadows from hills, mountains, and crater walls. The advancing terminator unveils new landscapes day by day when the Moon is waxing, then hides them in darkness day by day when waning. In between at when the Moon is full, the terminator lies all around the Moon's edge out of sight.

Bright Planets

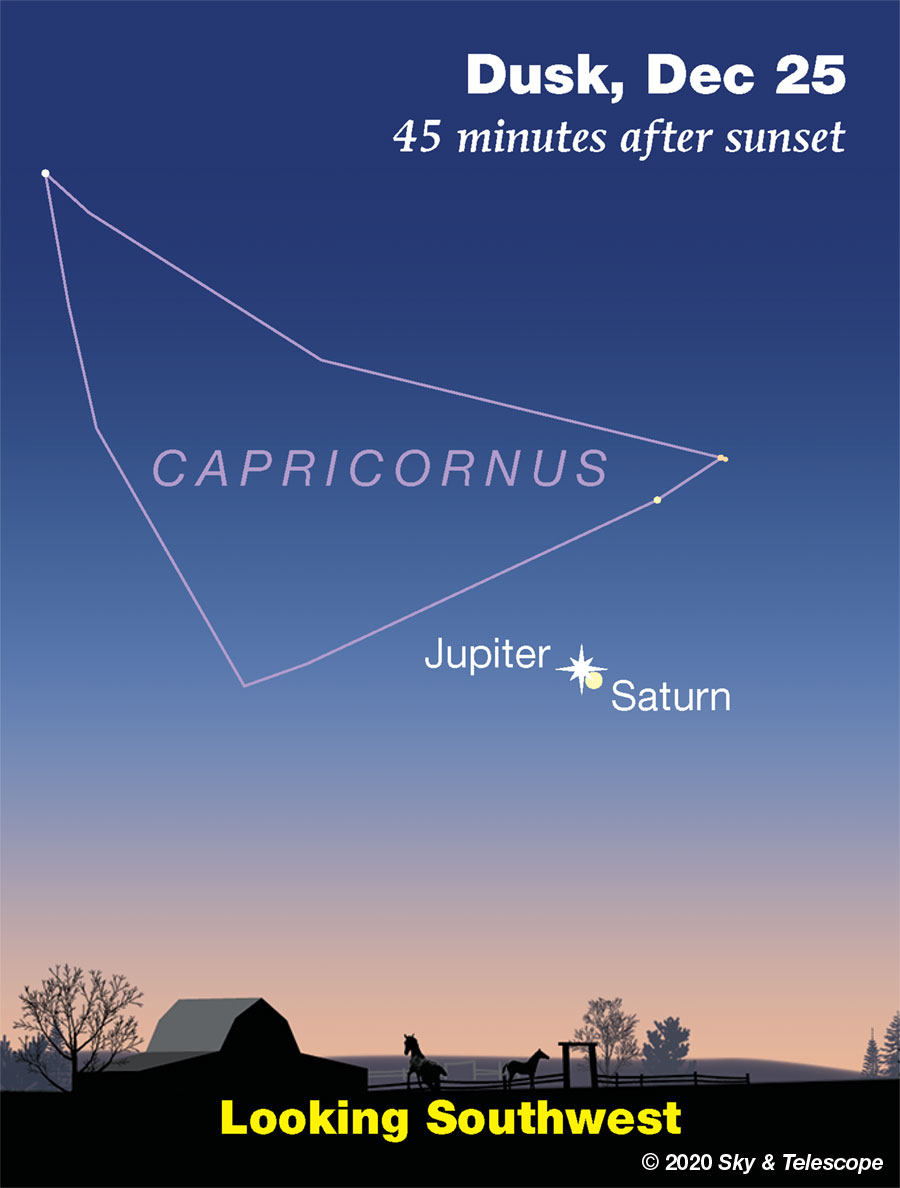

As it happens, this is a very special week for two of the bright naked-eye planets. Jupiter and Saturn shine strikingly close together very low in the southwest in twilight. The best time to look for them is about 40 to 50 minutes after sunset.

Find a spot with a good view low to the southwest. Their pair-up this week is a special coincidence for the inauguration of your new scope! But don't expect to see much of any detail on either planet. When you're looking this low in the sky you're looking through very thick layers of air, which severely fuzz up the magnified view. Still, there they are. Make their close-up acquaintance!

Mars, meanwhile, shines very high in the south during and after dusk. It's the only bright point there, shining pale yellow-orange . Nothing else in that part of the sky is nearly as bright. Tonight you'll find Mars off to the right of the Moon.

Mars passed unusually close to Earth last October, but that was then and this is now. It has receded into the distance and is currently a tiny dot, smaller than Jupiter or Saturn and slightly gibbous. Its orange color comes from the rusty dust that coats most of the bleak Martian deserts.

The other two bright planets? Venus shines just above the southeast horizon in early dawn. And Mercury is out of sight near our line of sight to the Sun. Don't worry, they too will have their day, just not for a while. Astronomy teaches patience.

More New-Telescope Sights

There's more to the night sky than the Moon and planets, of course. Winter evenings often bring crisp, transparent skies with a grand canopy of stars. But with so many inviting targets overhead, where to point first?

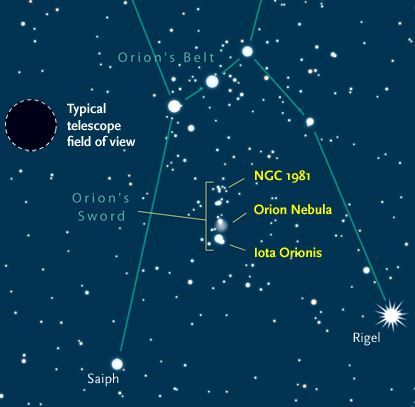

Here's a suggestion! The familiar constellation Orion climbs the southeastern sky in the evening these weeks. In its middle, look for the three-star line of Orion's Belt. The Belt is almost vertical as it rises in early evening, and is diagonal (as shown in below) late at night.

Just a few degrees south of the Belt (that is, a few finger-widths at arm's length) runs a smaller, dimmer line of stars: Orion's Sword. Within it lies the Orion Nebula, a luminous cloud of gas and dust where new stars are forming by the hundreds. It shows pink in most photographs, but to the human eye it's dim gray with a hint of green. The nebula is evident in any telescope once you get pointed at it, and so is the tight quartet of young stars near its center, known as the Trapezium. Astronomers refer to the Orion Nebula as Messier 42 (M42), and you'll see it labeled that way on star charts. Located about 1,400 light-years away, it's the closest massive star-forming nebula to Earth.

Joshua Rhoades / S&T Online Photo Gallery

Dim objects like nebulae are best seen when the sky is moonless and really dark, not like now. But by New Year's the Moon will be gone from the early-evening sky, allowing deeper darkness.

You can use Orion's Belt as a pointer to other things. Extend its line far upward, past the relatively bright star Aldebaran (the orange eye of Taurus, the Bull) and you'll reach the little cluster of stars called the Pleiades. It's about the size of your fingertip at arm's length.

Through binoculars or a telescope at its lowest magnification, the Pleiades cluster shows dozens of stars. Astronomers have determined that the cluster has about 500 in all. Like other star clusters, the Pleiades are held together by their mutual gravity. This one is classed as an open cluster for the stars' relatively uncrowded arrangement. It's nearby as star clusters go, traveling through space as a swarm about 440 light-years away.

The Pleiades stars, astronomers have determined, began to shine only about 70 to 100 million years ago. This makes them mere toddlers compared to our Sun and solar system, which are 4.6 billion years old. M45’s youthful suns are astonishingly energetic. Alcyone (al-SIGH-oh-nee), the brightest, is at least 350 times as luminous as our Sun. Like the other bright Pleiads it gleams with an intense blue-white light — a sign that it’s unusually hot and massive.

Next Steps in Astronomy

To find much else in the night sky, start learning the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope — the same way you need to know the continents and countries on a globe of Earth before you can pinpoint, say, Milan or Shanghai. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope magazine, the essential magazine of astronomy (ahem).

You'll also want a good, detailed star atlas (set of maps), such as the widely used Pocket Sky Atlas; a good deep-sky guidebook; and some practice in how to use the maps to pinpoint the aim of your telescope onto a something too faint to see with your eyes alone. There are certain key tricks to this — see Using a Map at the Telescope.

For more tips on skywatching and how to get the most out of your scope, see our Observing section and Getting Started section.

Whatever else, stick with it! Nobody is born knowing this stuff. Work your way into the hobby at your own pace, finding things to know and do and understand without worrying about everything you don't yet. Life in a big universe is like that.

7

7

Comments

Andrew James

December 30, 2020 at 3:48 pm

In understanding light grasp, pick any bright nighttime star and compare it to the naked eye, Then pick a nearby moderately naked eye bright star, compare it, then lastly a nearby naked eye faint star. This gives a rough perspective of magnitudes and the light gathered by the telescope. When later looking for stars or stellar clusters found below naked-eye visibility, the proportional differences of brightness becomes clear.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

December 30, 2020 at 3:50 pm

As S&T says elsewhere: "Keep in mind that "seeing" while at the eyepiece is an art as well as a skill. The more you observe, the more you’ll see. "

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

December 30, 2020 at 3:52 pm

New observers should look at wide double stars. At this time of year Mintaka / Delta Orionis, being the topmost star (right one) of Orion's Belt in the figure above might be best. The companion is easily spotted. To test magnification, try using different eyepieces, and see the differences in apparent separations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

December 30, 2020 at 3:52 pm

See Alan Adler's ''Pretty Double Stars for Everyone' is helpful. https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/celestial-objects-to-watch/pretty-double-stars-for-everyone/

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Greg-Redfern

January 1, 2021 at 3:51 pm

When you are ready to look at astrophotography, you will need a guiding hand. Be sure to consider my Springer Astronomy book, "Astrophotography Is Easy! Basics for Beginners", featured in S&T's February 2021 issue.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

January 1, 2021 at 5:02 pm

Gosh. "When you are ready to look at astrophotography..." is awfully presumptuous don't you think? I've been a visual observer for decades and I've never been tempted or particularly interested in imaging at all. Amateur astronomy is more about experiencing the Heavens will your own eyes or through your own telescopes. Looking at Saturn or the craters on the Moon alone is a life-changing experience because it is a one on one relationship connecting you to the whole universe. It is also humbling and the reason why telescopes are sold in the first place!

IMO, your statement openly implies you are second rate novice if you don't come an imager, which isn't quite true. (So much so, you've inspired me to start writing a counter article for my own website about the illusion that astrophotography is the pinnacle amateur astronomy.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

January 1, 2021 at 6:45 pm

Now I'm worried. You brazenly state in your book Chapter 4 pg.56 "If you haven't done so already don't buy a telescope until you have read this book..." Your singular enticement for buying a telescope and camera seems based solely on the premise that astrophotography lets you to "...venture further out into space and time." What you don't say is that many images are already available on the Internet - both professional and amateur - meaning you can do the same without the cost. I'd also think imaging is greatly limited by urban environments and light pollution, but this issue seems understated.

Would it not be better (and cheaper) to join an astronomical society first, and experience this firsthand with other amateur astronomers?

Lastly, pg.55 of the bat states: "When you take a picture of any astronomical object you are going back in time." But when you look through a telescope aren't you also looking back in time too? Surely the latter is far more profound and real? e.g. The starlight falling onto the retina is 'now' and it has taken a significant time to cross the void since released from the star as photons. Images are merely accumulation of light spread over the exposure time. They are essentially historical records.

I look forward to read the full eview in S&T Feb. 2021 issue.

Note: You talk about the 'astrophotography bug'. Is a vaccine available for that? 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.