The annual Lyrid meteor shower will add some pop and sizzle to Saturday's pre-dawn sky. With little interference from the Moon, conditions are ideal for meteor watching.

Sky & Telescope diagram

I've always liked the "April showers" synergy between the annual Lyrid meteors and the rain that encourages the return of familiar spring wildflowers.

It's been three months since January's Quadrantids, the last major meteor shower, so I think we're primed for a show. If clear sky prevails Saturday morning (April 22nd), we might expect to see between 10–20 meteors per hour under dark, moonless skies.

The radiant is located in eastern Hercules near the border with Lyra, well up in the eastern sky by local midnight. Best viewing should occur between between 2 a.m. and dawn Saturday when Hercules rides high in the south. Expect little lunar interference — the waning crescent won't rise until shortly before the start of morning twilight.

NASA

Despite the location of its radiant, the Lyrids have always been associated with Lyra because of Vega's visual dominance and the original loosey-goosey nature of constellation outlines. For centuries, where one constellation ended and another began was subject to interpretation. The Lyrids shot out of the sky close enough to Lyra and eye-catching Vega to assume its name. Had the shower emerged after the International Astronomical Union set precise constellation borders in 1930, we’d be calling them Herculids!

Robert Lunsford of the American Meteor Society predicts this year's shower will peak around 17 UT on April 22nd. Since that's 1 p.m. EDT / 10 a.m. PDT, North American observers will see it best in the hour or two before dawn Saturday. For many of us, that's somewhere between 3 and 5 a.m. Just check your local sunrise time and dial it back about three hours to arrive at the best viewing hour.

You can also watch the shower on the mornings either side of maximum, though rates will be reduced. Like most meteor showers, the Lyrids originate from comet dust, in this instance, dust from Comet Thatcher (C/1861 G1), which traces out a 415-year-long orbit around the Sun. Earth intersects the comet's path in late April each year, and meteoric fireworks result.

The animation above, created by Ian Webster using data from Peter Jenniskens, shows Earth intersecting the meteor stream associated with Comet Thatcher on April 22nd this year. You can explore this interactive visualization as well as visualizations for other meteor showers at meteorshowers.org. Just click with the mouse button and use your scroll wheel to vary distance and perspective.

J. Kelly Beatty (S&T)

The average velocity of a Lyrid is 48 km/sec (30 miles/second, or 108,000 mph). An encounter with our atmosphere at that speed vaporizes the comet fragment (called a meteoroid). As the particle crashes through the air, it leaves a linear trail of excited and ionized air molecules.

A moment later, when each molecule returns to its "relaxed" state, it releases a photon of light. The combined emission of billions of photons creates the temporary bright streak we call a meteor. If the streaks continue to glow for several seconds or longer, they're referred to as meteor trains.

Watching the shower is easy. All you have to do is look up. Find as dark a location as possible, away from the direct glare of street and yard lights. Snap open a folding chair, lean back, and snuggle under a blanket or sleeping bag to keep warm. Assuming you're out when the radiant is high in the sky, face southeast or south, although truth be told, any direction will do. You'll know you're seeing a Lyrid if you can trace its trail back in the direction of Hercules/Lyra.

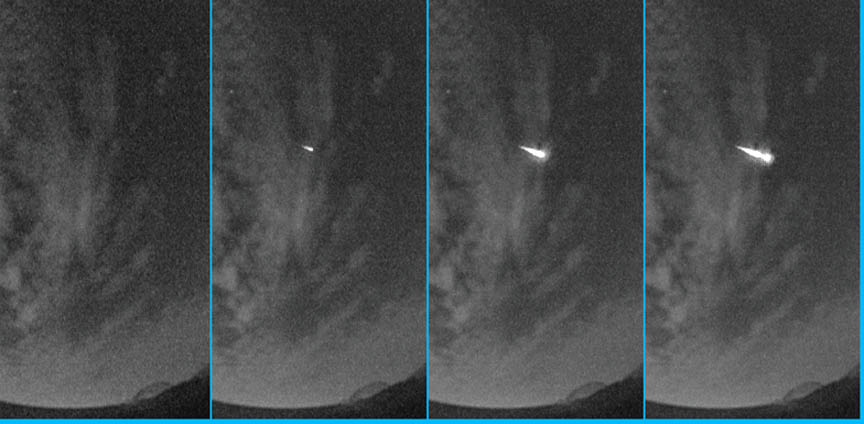

NASA all-sky camera / Bill Cooke / MSFC

The Lyrids are generally fast and bright — about as speedy as the Perseids — and not only produce trains, but also occasional fireballs. They're also prone to outbursts when the Earth happens to pass through a denser filament of comet debris; the most recent occurred in 1982 when 90 per hour were recorded at its peak. In 1803, that number surpassed 500 per hour!

As you ease back Saturday, enjoying a celestial take on April showers, know that you're one of a long line of skywatchers who's thrilled to the Lyrids since they were first recorded by Chinese astronomers more than 2,700 years ago.

4

4

Comments

Bob

April 22, 2017 at 2:03 pm

Most interesting. I liked Ian Webster's Lyrids animation, as well as J. Kelly Beaty's Grape-Nuts comparison and Don Pettit's photo made from the International Space Station.

Unfortunately, my observing location was all clouds and rain this morning.

Bob

Kentucky

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 23, 2017 at 4:50 pm

Sorry to hear it, Bob. I stayed up late Friday night observing and even later watching and photographing the aurora, so by 2 a.m. I just couldn't bring myself to stay up any longer to catch the best part of the Lyrid shower. Darn northern lights!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Aqua4U

April 23, 2017 at 12:21 am

I was too zonked out to stay up to see these meteors as Thurs night I stayed up a bit too late with my telescope. That night I caught Comet C/2015 V4 (Johnson), which was my 55th comet. The predictions said it would be around mag. 9.5 Instead I estimated it at mag. ~8. It's possible(?) that last week's CME from Mr, Sol brightened it? Hmm... I am mentioning this because that comet is in almost the same part of the sky (Upper right part of Hercules) passing Phi Herculis and heading southwest from there. Comet Johnson had a fair sized coma with small but bright nucleus and a discernible with averted vision dust tail. So, if you are out there to observe the Lyrids, you might as well give it look-see? I'd appreciate a magnitude estimate from a pro!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 23, 2017 at 4:48 pm

Hi Aqua,

I'll be writing about C/2015 V2 Johnson soon. It's been gradually brightening up, so I don't think the recent CME is related. CMEs can snap off ion tails, but they typically don't make comets brighter. I spotted it in 10x50s Friday night (April 21) and estimated magnitude +8.5. Very easy to see and not much fainter than 41P. Watch for it to brighten even more later this spring.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.