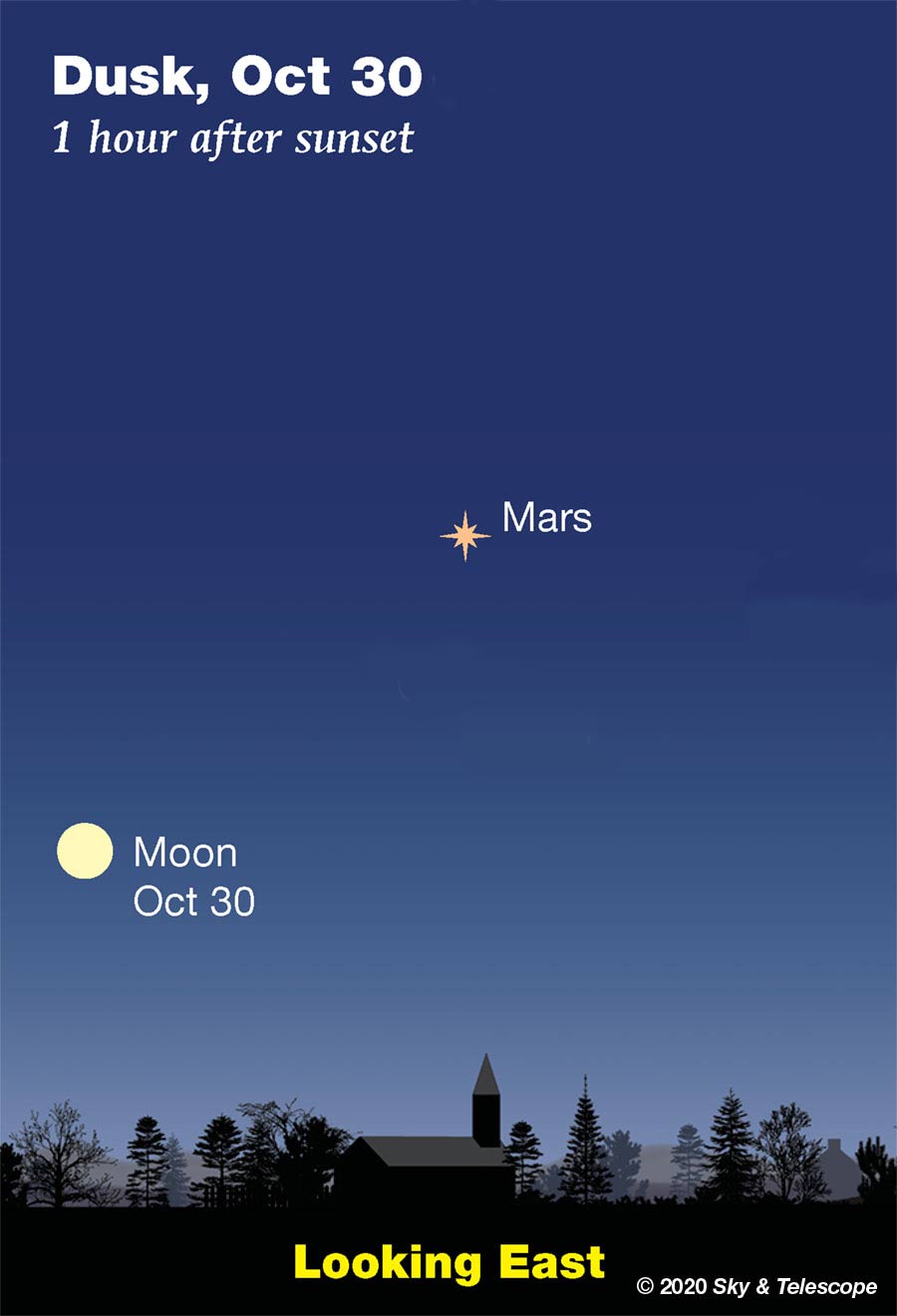

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 30

■ The Moon, barely short of full this evening, shines lower left of Mars as shown above. By 10 or 11 p.m. they're lined up horizontally high in the south.

■ Vega is the brightest star very high in the west at this time of year. Its little constellation Lyra extends to its left, pointing as always to Altair, which is currently the brightest star high in the southwest.

Three of Lyra's leading stars, after Vega, are interesting doubles. Barely above Vega is 4th-magnitude Epsilon Lyrae, the Double-Double. Epsilon forms one corner of a roughly equilateral triangle with Vega and Zeta Lyrae. The triangle is less than 2° on a side, hardly the width of your thumb at arm's length.

Binoculars easily resolve Epsilon. And a 4-inch telescope at 100× or more should resolve each of Epsilon's wide components into a tight pair.

Zeta Lyrae is also a double star for binoculars; much tougher, but well resolved in a telescope.

And Delta Lyrae, a similar distance upper left of Zeta, is a much wider and easier binocular pair.

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31

■ Full Moon and Mars for Halloween. The full Moon (it was exactly full at 10:49 a.m. EDT) rises in the east about a half hour after sunset, depending on your location. This is the second full Moon in calendar October in many of the world's time zones, including those of the Americas, making it a "blue moon" for these places.

The bright orange dot shining well off to its upper right is Mars. They're about three fists at arm's length apart, more than yesterday illustrated above. Because every day, the Moon moves about 15° farther east along its orbit.

■ Once the night is fully dark, look above the Moon by about a fist and a half for the modest stars of little Aries. Can you make them out through the moonlight?

Above Aries, by a roughly similar amount, is the much longer line of stars forming the main line of Andromeda, roughly horizontal and two or three fists from end to end.

■ Meanwhile, bright Jupiter and more modest Saturn still hang together in the west-southwest.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 1

■ Around 9 p.m. standard time, depending on where you are, zero-magnitude Capella rises exactly as high in the northeast as zero-magnitude Vega has sunk in the northwest. How accurately can you time this? Astrolabe not required. . . but it might help.

■ Daylight-saving time ended and standard time began at 2 a.m. on this date for most of North America. Clocks fall back an hour.

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 2

■ The waning gibbous Moon rises around the end of twilight, about 10° below the Pleiades (for North America). Rising below the Moon not long afterward is Aldebaran. The Moon and Aldebaran accompany each other about 4° apart as they climb higher through the evening.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 3

■ Now the waning gibbous Moon rises about a half hour after the end of twilight. Aldebaran shines to its right or upper right, and brighter Capella sparkles twice as far to the Moon's upper left. Above Aldebaran are the Pleiades.

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 4

■ The Summer Triangle Effect. Here it is November, but Deneb still shines near the zenith as the stars come out. And brighter Vega is still not far from the zenith, toward the west. And the third star of the "Summer" Triangle, Altair, remains very high in the southwest (high over Jupiter and Saturn). They seem to have been there for a couple months! Why have they stalled out?

What you're seeing is the result of sunset and darkness arriving earlier and earlier during autumn. Which means if you go out and starwatch soon after dark, you're doing it earlier and earlier by the clock. This counteracts the seasonal westward turning of the constellations. If you made a point of always doing your skywatching at the same time by the clock, the constellations would proceed as normal.

Of course the "Summer Triangle effect" applies to the entire celestial sphere, not just the Summer Triangle. But the apparent stalling of that bright landmark inspired Sky & Telescope to give the effect that name many years ago, and it has stuck ever since.

Of course, as always in celestial mechanics, a deficit somewhere gets made up elsewhere. The opposite effect makes the seasonal advance of the constellations seem to speed up in early spring. The spring-sky landmarks of Virgo and Corvus seem to dash away westward from week to week almost before you know it, due to darkness coming ever later. We can call this the "Corvus effect."

■ In early dawn Thursday morning, look for 3rd-magnitude Gamma Virginis just 1.1° left of brilliant Venus low in the east (for North America). Binoculars will help.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 5

■ When night arrives, the Great Square of Pegasus is still balanced on its corner high in the southeast. But within two hours it turns around to lie level like a box high in the south.

A sky landmark to remember: The west (right-hand) side of the Great Square points far down almost to 1st-magnitude Fomalhaut. The east side of the Square points down toward Beta Ceti (though not as directly, and not as far).

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 6

After dark this week, Capella shines well up in the northeast. Look for the Pleiades three fists to Capella's right. As evening grows later, you'll find orange Aldebaran climbing up below the Pleiades.

Then by about 10 p.m. (depending on your location), Orion clears the eastern horizon below Aldebaran.

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 7

■ Vega is the brightest star in the west in early evening. Its little constellation Lyra extends to its left. Somewhat farther left, about a fist and a half at arm's length from Vega, is 3rd-magnitude Albireo, the beak of Cygnus. This is one of the finest and most colorful double stars for small telescopes.

Farther on in the same direction you come to 3rd-magnitude Tarazed and, just past it, 1st-magnitude Altair.

■ With the Moon gone from the evening sky, now's a fine time to explore the telescopic riches of the Milky Way in and around the mouth of Cepheus very high in the north. Use the Deep-Sky Wonders article, charts, and photos in the November Sky & Telescope, page 54.

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury rapidly emerges into dawn view in the later part of this week. By the morning of Wednesday November 4th look for it low in the east-southeast, well below Venus, about 45 minutes before sunrise. It has brightened to magnitude 0 by then and should be easy to see.

Venus (magnitude –4.0, in Virgo) shines brightly in the east before and during dawn, not very high. Venus rises in darkness about an hour before dawn's first light. Once dawn gets under way, it's nicely up as the "Morning Star." Can you keep Venus in view all the way to sunrise and maybe after? Binoculars help as the sky grows bright with day.

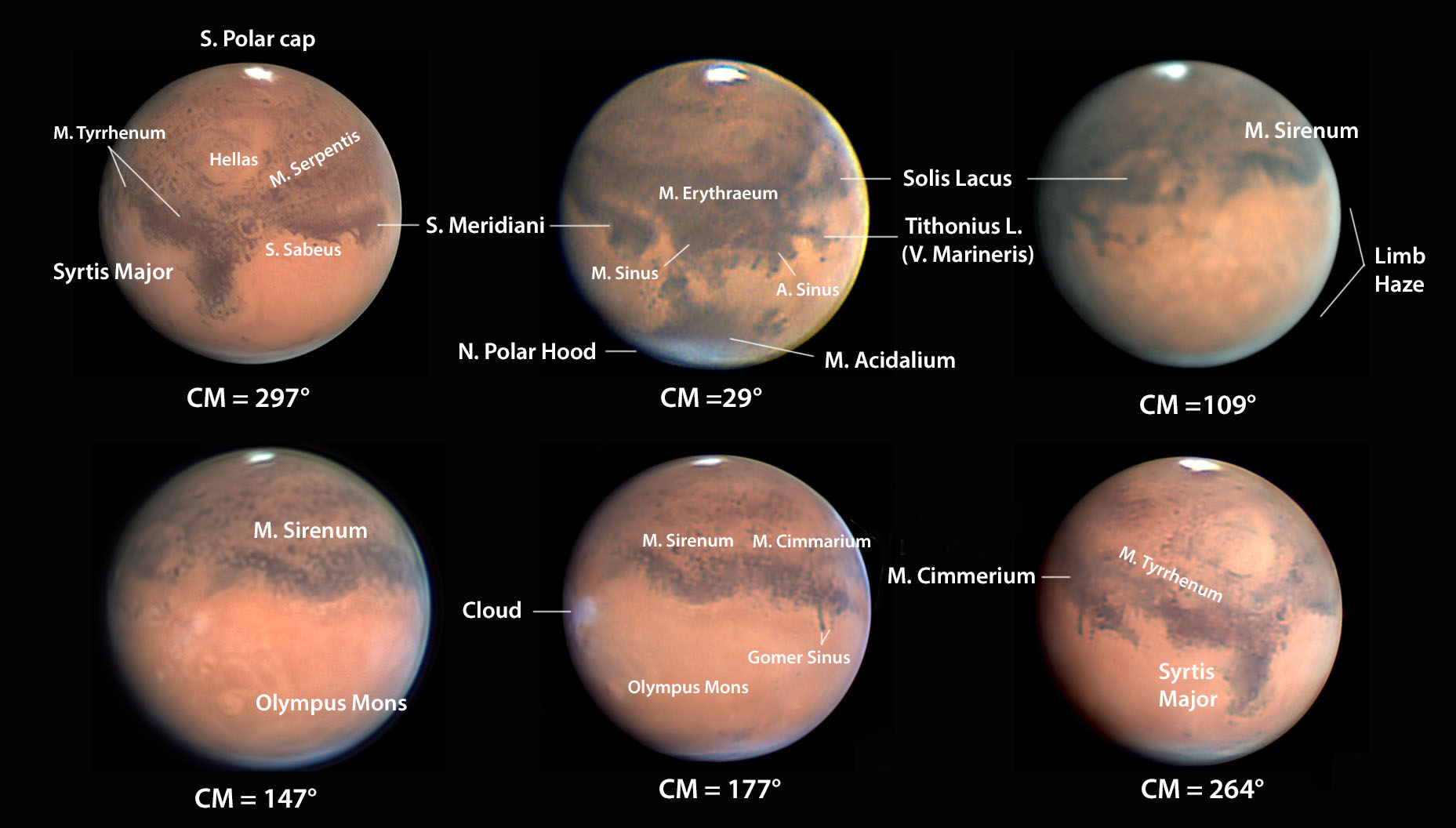

Mars (about magnitude –2.0, in Pisces) is three weeks past opposition and noticeably less bright. This week it shrinks from 20 to 19 arcseconds wide in a telescope, still plenty large to show good surface detail during steady seeing.

And it climbs into high view earlier every night! At dusk Mars glares fiery orange in the east-southeast. It's at its highest and best in the south by 10 p.m. standard time.

See Bob King's "A Great Year for Mars" in the October Sky & Telescope, page 48, and his Behold Mars! online. To get a map of the side of Mars facing Earth at the date and time you'll observe, you can use our Mars Profiler. The map there is square; remember to mentally wrap it onto the side of a globe. (Features near the map's edges become very foreshortened; compare with the images above.)

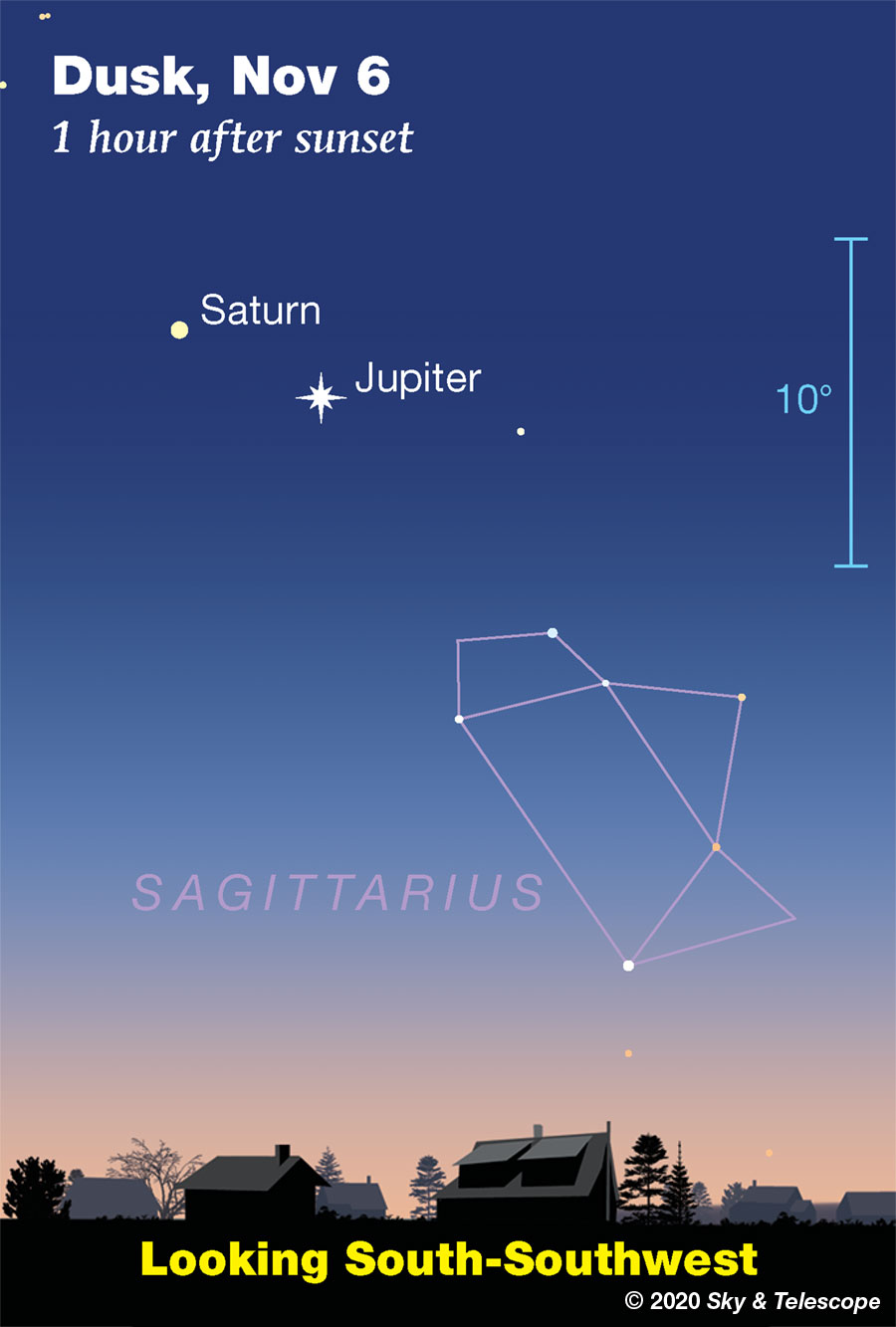

Jupiter and Saturn (magnitudes –2.2 and +0.6, respectively) tilt down in the west-southwest during and after twilight. Get your telescope on them early, before the end of twilight, before they sink lower toward the southwest later in the evening. But don't expect much; both are somewhat farther and smaller than they were during summer, and the seeing that low will likely be poor.

Jupiter is the bright one; Saturn is now only 5° to its upper left. Watch them creep toward each other for the rest of the fall. They'll pass just 0.1° apart at conjunction on December 21st, low in twilight, as fall turns to winter.

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, in Aries) is high in the east by 8 p.m. standard time, about 20° east of Mars. Uranus is only 3.7 arcseconds wide, but that's enough to appear as a tiny fuzzy ball, not a point, at high power in even a good small telescope.

Neptune (magnitude 7.8, in Aquarius) is equally high in the south at that time. Neptune is 2.3 arcseconds wide, harder to resolve except in good seeing. Check in on them when you're done with Mars: Finder charts for Uranus and Neptune.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time, EDT, is Universal Time minus 4 hours. Eastern Standard Time, EST, is Universal Time minus 5 hours.(Universal Time is also known as UT, UTC, GMT, or Z time.)

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. The next up, once you know your way around, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And be sure to read how to use sky charts with a telescope.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, or the bigger (and illustrated) Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don't think, and not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically, meaning heavy and expensive. And as Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty's monthly

podcast tour of the heavens above. It's free.

"The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It's not that there's something new in our way of thinking, it's that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before."

— Carl Sagan, 1996

"Facts are stubborn things."

— John Adams, 1770

10

10

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

October 30, 2020 at 4:13 pm

Uranus is at opposition to the Sun on Saturday October 31, just an hour after the Moon's opposition to the Sun, i.e. full Moon, so they're within a few degrees of one another in the sky on Friday and Saturday nights. The full Moon at magnitude -12.2 is about 1.4 million times brighter than Uranus at magnitude 5.7.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

October 30, 2020 at 9:01 pm

Anthony Barreiro, advise if you view Uranus at opposition with your telescope. My area just had portions of zeta pass by leaving cloudy skies now until perhaps Monday, so the forecast 🙂 Looks like at 129x or more, you can resolve Uranus as a planetary disk shape (in the past I did). Earlier this month I enjoyed some excellent views of Mars using my 90-mm refractor telescope and 10-inch Newtonian. Starry Night and Stellarium show various stars within 2-degrees or less of Uranus, the stars can be seen in the eyepiece near Uranus too---Rod

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 31, 2020 at 2:18 pm

Thanks Rod. At 2235 PDT last night I was looking at the full Moon and noticed Menkar, alpha Ceti, to the Moon’s lower left. Using 10×42 binoculars I star-hopped to Uranus, which was just over 5 degrees from the Moon, so the Moon was just outside the field of view, but still very bright.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 31, 2020 at 2:16 pm

Whoops, I missed a decimal place. Magnitude -12.2 is about 14.5 million times brighter than magnitude 5.7

You must be logged in to post a comment.

LenW

October 31, 2020 at 1:48 am

S&T itself has explained that a Blue Moon is not the second full moon in a month, but is the third full Moon in an astronomical season containing 4 full moons (a less common occurrence). Since only about 2 out of 5 years have 13 FMs, usually only those years will have a BM (thus, 'once in a blue moon'). Full moons have traditional names, arranged by season, so having 4 in one season leaves an unnamed one, which became the BM.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

October 31, 2020 at 12:03 pm

I checked Stellarium and Starry Night. The nearly Full Moon (1449 UT 31-Oct) will be close to 6-degrees angular separation from Uranus in Aries. Uranus will be a difficult target to see using binoculars or a telescope tonight. I set the Stellarium and Starry Night to 0030 UT for my location and checked (2030 EDT). Uranus near 1:00 position of the Moon, could be fun to see but my area with clouds. Uranus magnitude listed as +5.66 tonight using Stellarium and Starry Night latest edition. A difficult to observe opposition because of the Moon 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

November 1, 2020 at 2:21 pm

Anthony Barreiro, I tried to view Uranus last night with my 10x50 binoculars but that rising Great Pumpkin in the sky was very bright 🙂 I could see the star Mu Ceti in the field of view, that was interesting. The Moon just past apogee and some 400,000 km or more away while the star about 84 LY distance. Altocumulus clouds rolled in for the remainder. I checked ahead using Stellarium and Starry Night. Uranus and Mars are a bit more than 3-degree apart on the ecliptic, 14-Jan-21 near 2117 EST for my location and SF city time, 1817 EST. Both are in Aries. Using your 10x42 binoculars on a clear night, you may be able to see both planets in the binocular field of view. Mars ends retrograde motion in Pisces on 15-Nov-2020 so will be moving eastward again through Pisces and into Aries, closing in on Uranus 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

November 1, 2020 at 6:06 pm

Okay, SF time 1817 EST is 1817 PST, whoops, oops, 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

November 1, 2020 at 6:46 pm

Thanks for the heads up. Something to look forward to in the new year. Let's hope for clear skies for the 21 December 2020 Jupiter-Saturn conjunction.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

November 2, 2020 at 9:55 pm

mary beth, New Jersey Eclipse Fan, Anthony et al. Some of you may like my note on observing the Moon and Epsilon Tauri star tonight, https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/watch-moon-winter-hexagon/

I could see both in the field of view and the star has a large exoplanet orbiting it 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.