New analyses suggest that an asteroidal fragment's collision with Earth on February 15, 2013, might not be the once-per-century event that researchers thought. Instead, these potent wallops might occur more frequently — and with more destructive power — than previously thought.

On February 15, 2013, a large meteoroid exploded in the sky over Chelyabinsk, Russia, delivering the most powerful cosmic blast in the past century.

Uragan.TT / Wikimedia Commons

Anyone living in Chelyabinsk, Russia, and who looked skyward at precisely 9:20:32 a.m. last February 15th, saw the incredible spectacle of a massive meteoric fireball brighter than the early-morning Sun. It broke apart violently 20 to 30 miles (30 to 45 km) up. Then, 88 seconds later, powerful shock waves knocked some residents off their feet, injured more than 1,000 (including flash-induced sunburns), and shattered windows in nearly half of the city's apartment buildings.

Scary close-call aside, scientists count themselves fortunate that the cosmic blast occurred over this urban center. That's because the city's security-obsessed residents captured the event in a myriad of building-mounted video cameras and on dashcams mounted inside their cars. All these looks, combined with defense satellites looking down on Earth from space and a worldwide infrasound network maintained by Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), have allowed researchers to dissect the event with unprecedented precision. Yesterday they made their findings public, in two articles published in Nature and a third in Science.

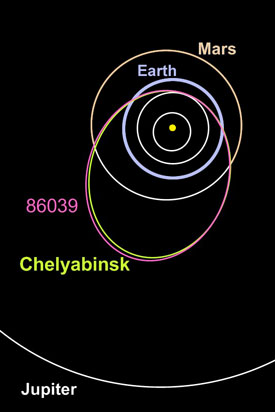

Prior to hitting Earth, the Chelyabinsk impactor had an orbit very similar to that of the unnamed asteroid 86039.

Jiří Bobrovička

The object itself was a wayward interloper from the asteroid belt. Careful trajectory reconstruction by Jiří Borovička (Astronomical Institute, Czech Academy of Sciences) and others shows that the object came in on a highly elliptical, low-inclination orbit that's a close match to that of the unnamed asteroid 86039. Mostly likely, the two bodies were once part of a single object that sent fragments flying across Earth's path after a violent collision with another asteroid some time in the past.

Researchers have also pulled together estimates of the impact's energy, gauged as the kinetic-energy equivalent of exploding TNT. A research team led by Peter Brown (University of Western Ontario), visible-light emission alone implies a blast of at least 470,000 tons (470 kilotons) of TNT. But the powerful seismic shock yields a rather uncertain "best estimate" of 430 kilotons, while sensors on military satellites suggest 530 kilotons. Finally, records from the CTBTO's infrasound network imply a somewhat higher yield of 600 kilotons.

Uncertainties aside, the Chelyabinsk blast represents the most energetic impact on Earth since the iconic blast over the Tunguska region of Siberia in 1908. The rocky object had a diameter close to 62 feet (19 m) and a mass of roughly 12,000 metric tons (nearly twice the initial estimate).

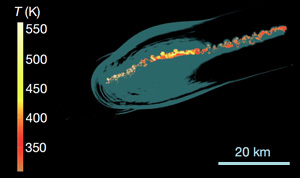

A color-coded computer model of temperatures inside the residual trail left by the Chelyabinsk bolide, at a time 50 seconds after the object exploded. Note that the outer gray envelope has a roughly cylindrical shape, indicating that the expanding shock wave came from a linear chain of disrupting fragments.

Peter Brown & others

The ground-level damage might have been much greater, researchers conclude, save for two fortunate circumstances. First, the body came in at a very shallow angle, just 17° from horizontal. As it broke up, the resulting shock wave expanded with a cylindrical shape, rather than from a single explosive point, which tended to spread the shock energy over a wider, less concentrated area. Had the flight path been more vertical, as was the case with the Tunguska blast, the damage would likely have been far more extensive.

Second, recovered fragments show that the incoming object was a single cohesive body — but only barely so, according to analysis by the "Chelyabinsk Airburst Consortium," led by Olga Popova (Institute for Dynamics of Geospheres, Russian Academy of Sciences).

This fragment from the Chelyabinsk impactor, about 4cm across, shows crisscrossing fractures that are filled with shock-melted material.

Olga Popova & others

The teams reports that the Chelyabinsk parent body must have endured an abrupt thermal or collisional event 4.45 billion years ago, 115 million years after the solar system formed, that left its interior crisscrossed by a network of fractures filled with metal-rich glass. These preexisting fractures, explains consortium member Peter Jenniskens (SETI Institute), "left the body weaker, and it broke apart along those veins."

But researchers are hardly feeling complacent about all this. For example, Brown and his team went on to compile a worldwide catalog of all such airbursts over the past two decades. (Chelyabinsk might have been the most powerful, but it wasn't the only one recorded.) They find that the impacts from objects a few tens of meters across must be occurring 7 to 10 times more frequent than estimates based only on telescopic surveys, though there's a lot of uncertainty because the events are so sparse. Still, Brown's census suggests that a Chelyabinsk-type blast should happen not just once per century on average, as had been thought, but instead every few decades.

Another concern is researchers didn't believe objects in this mass range would disintegrate so low in the atmosphere. Now the thinking is that these blasts are driven deeper down by their own momentum, an idea first put forward six years ago by Mark Boslough (Sandia National Laboratories) to explain Tunguska's 800 square miles of devastation. Moreover, Boslough points out, impacts appear to be "more damaging than nuclear explosions of the same yield" because up to half the energy in a nuclear blast escapes as radiation rather than as shock and heat.

It's a set of results both exciting and sobering. Millions of Earth-threatening objects with masses comparable to Chelyabinsk's have yet to be discovered. To make matters worse, February's rogue impactor approached from Earth's sunlit side, making it impossible to detect beforehand.

So what's the "action plan" to defend Earth from objects once considered too small to do any real damage? Ideas are being kicked around. A team at the University of Hawaii hopes to operate a Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) by 2015. The privately funded B612 Foundation has proposed its Sentinel spacecraft, which would scan the infrared sky from a location well inside Earth's orbit. Conceptually similar is NEOCam, first proposed in 2005.

Meanwhile, NASA managers have launched a "Grand Challenge" to bring innovative concepts to light, and the United Nations is trying to establish an "International Asteroid Warning Group".

These are useful first steps toward a more comprehensive global strategy. But some researchers wonder whether February's eye-opener, combined with the realization that relatively small asteroids can do serious damage, should spur a more rapid buildup of detection and defense systems. One has to wonder how different the response would have been had that errant space rock come in over Chicago, instead of Chelyabinsk.

10

10

Comments

[email protected]

November 7, 2013 at 5:13 pm

Kelly, I'm curious about the mass you quoted, of 1,200 Metric Tonnes (MT). Given the quoted diameter of 19 m, a sphere of that diameter would be about 3,600 m^3, and if it were about twice as dense as water, it's mass would be 7,200 MT. Even then, it would have to be really tearing thru the atmosphere, at about 25 km/sec (over twice the minimum speed), to have a kinetic energy near 500 Kilotons. Your thoughts?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Gerald Hanner

November 8, 2013 at 8:37 am

That estimated frequency of once per several decades may be closer to the truth. Although it probably didn't make it outside of aviation circles. I recall an incident from the 1970s, over the north Pacific Ocean, in which a jet cargo hauler spotted a mushroom cloud rising from the ocean out ahead of them. Being unsure what it was, they circumnavigated it and a check of the aircraft, after it arrived in Anchorage, showed no radiological contamination. Since it was in the 1970s I would expect that DSP would have detected the event.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

bfrib

November 8, 2013 at 4:33 pm

During TV reporting early in the First Gulf War, I remember a comment that there was a large explosion over the Pacific Ocean, Southwest of Hawaii. It was surmised that a SCUD Missle had been fired and exploded there. Not another word was ever said about that event.

In retrospect, I believe this was an incoming space rock that was detected by the Military. It was probably hushed up

to cover up the capabilities that we had at that time to detect these kind of things. I would love to know more about what it was that detonated on that date.

Anyone???

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anton Szautner

November 8, 2013 at 5:16 pm

Looking at the similarities in their orbits, it occurs to me that another way that the Chelyabinsk body might have been wrested from the parent asteroid 86039 is through a close flyby of the Earth in the ancient past. While the orbit of asteroid 86039 doesn't currently bring it very near to Earth, it might once have crossed Earth's orbit and since been perturbed to its current orbit. It is at least conceivable that the Chelyabinsk body might once have been loosely attached to the surface like the boulders seen on asteroid Itokawa, or it may even have been a moonlet of the parent. A sufficiently close pass to Earth can have segregated them via tidal interaction, with the Chelyabinsk body eventually intersecting the Earth's atmosphere. If it was once one of many similar boulders loosely attached to the surface, it suggests the possibility of a fair population of them that may have been released by the same event. I wonder if there are known fireball orbits that are similar to that of asteroid 86039.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Geoff

November 8, 2013 at 5:50 pm

Has anyone analyzed the isotopic abundances? Any conclusions or surprised?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kelly Beatty

November 10, 2013 at 7:52 am

hey, gmonser6: my goof -- it should have been 12,000 MT (now corrected).

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Milos

November 10, 2013 at 2:44 pm

Let me correct a typo in the name of the main author: It should be Jiří Borovička (see http://www.asu.cas.cz/person/borovicka.html).

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Gerald Hanner

November 12, 2013 at 8:27 am

Bfrib asks about satellites being able to detect large meteors entering the atmosphere. Yes they can. Peter Brown, a meteor and comet researcher at University of Western Ontario has for many years used data recorded by DSP. WRT a large explosion southwest of Hawaii during Gulf War I, no SCUD did that and it probably was recorded by DSP.

I can recall an incident from the mid-1970s involving a jet cargo hauler flying from Japan to Anchorage. Somewhere out over the north Pacific Ocean they observed a mushroom cloud rising from the ocean. Being unsure of what it was, the circumnavigated the cloud. Radiological tests when the arrived at Anchorage found NO radiation. My guess is that it was another large meteor that went mostly unnoticed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bill Simpson

November 14, 2013 at 1:13 am

If you want to see what they can do, visit the, 'Impact Earth!' website of Purdue University. The energy from even relatively small ones can fry you from miles away. Even blast waves that arrive minutes later can level everything. Of course, the radiated heat probably set it ablaze first, so it doesn't matter much.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

mortimer zilch

November 17, 2013 at 6:10 am

SPACE ROCKS! - we need to get Rock-N-Roll in on this....world-wide fun(d) raising concerts for groups like B612 that are trying to actually DO something about protecting we Earthlings from these incoming impactors. "SPACE ROCKS CONCERTS" all across the globe!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.