If you own an 8-inch or larger telescope you might see more than a dozen new and returning comets this year, including one potential naked-eye candidate.

Damian Peach

I've got some good news and some bad news. First the good news. Oodles of comets are on their way in 2021. Now the bad. Most won't get brighter than 9th magnitude with the possible exception of Comet Leonard (C/2021 A1), a recent discovery that could rise to naked-eye visibility in December.

While waiting for Leonard to take the stage we'll have a steady stream of returning periodic comets plus new finds made by the ATLAS survey and NASA's NEOWISE space telescope. And remember, it's only January. If the past is any indication their ranks will swell as the year rolls on. An amazing 116 new comets were discovered in 2020, at least a half-dozen of which became bright enough to see in amateur telescopes and with the naked eye.

Below you'll find a map, time of best visibility, and additional information for each comet predicted to be brighter than magnitude 12. For current comet observations I used a 15-inch reflector under Bortle 4 skies. At the end of this article I'll discuss ways anyone can create their own detailed, personalized charts to track each and every one.

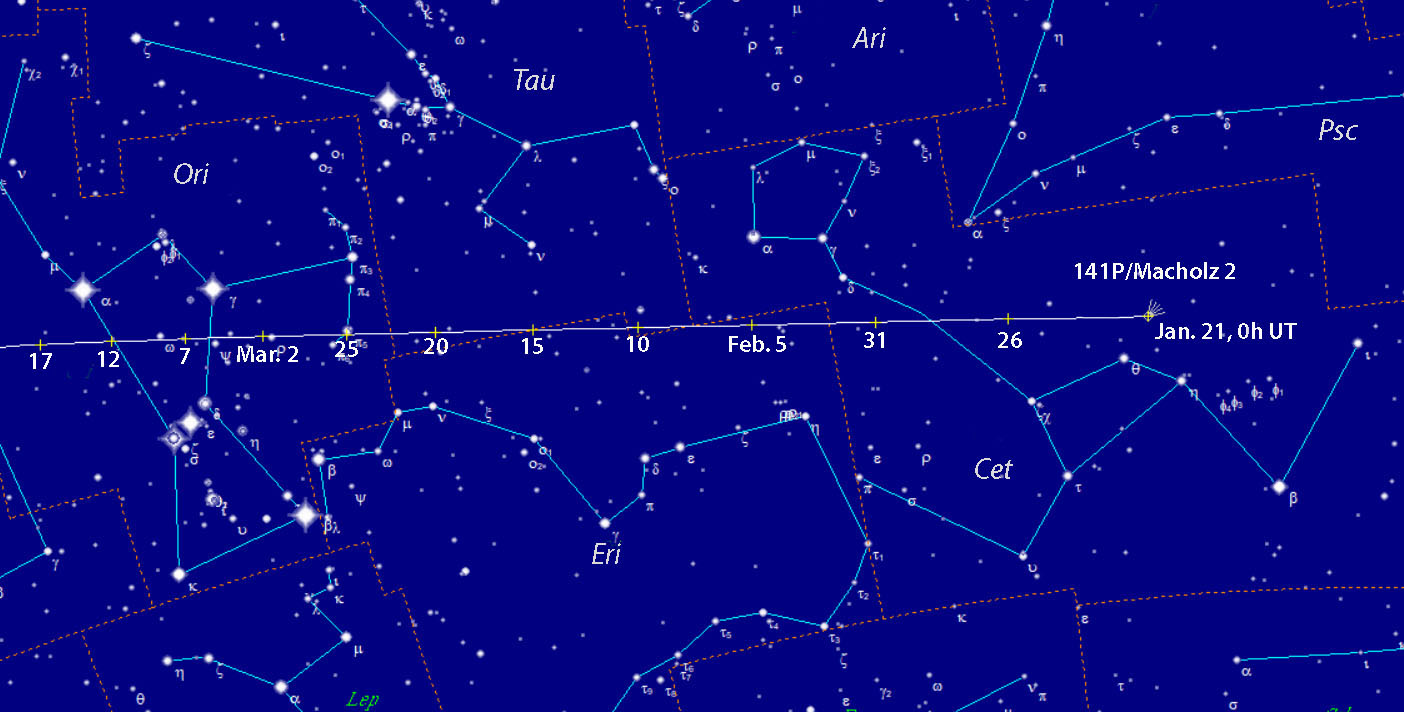

141P/Machholz 2

Evening sky — January to early February

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

Currently sprinting across Cetus, when I last observed 141P/Machholz 2 on January 8.04 UT it exhibited a diffuse, 10.5-magnitude coma ~4′ across with a brighter, somewhat condensed nuclear region. Its DC, or degree of condensation, was 3 on a scale of 0 (completely diffuse, no condensation) to 9 (starlike). Through a Swan Band filter, which enhances comets rich in carbon emissions, the coma appeared brighter and better defined.

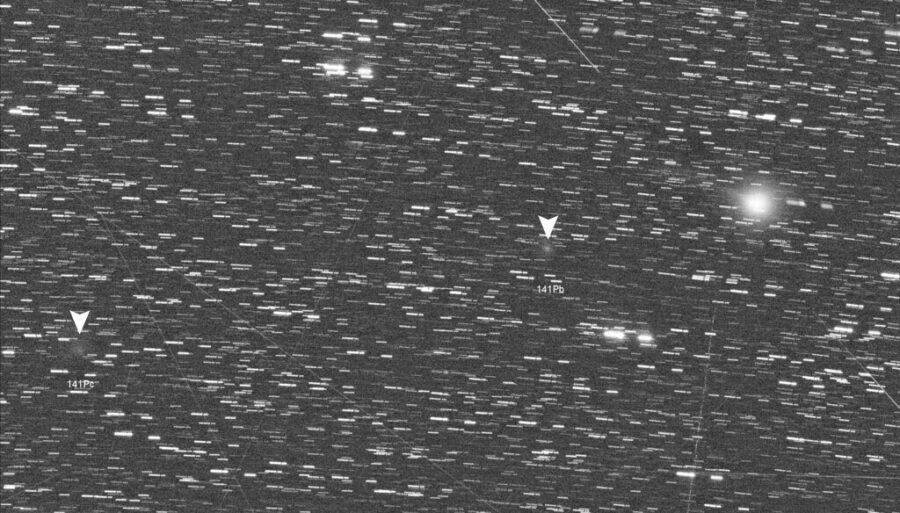

Michael Jäger

Machholz will fade in the coming weeks as it zips eastward from Cetus into Orion between now and the end of February. In yet another demonstration of just how fragile comets can be, two faint 16th- to 17th-magnitude fragments (141P-B and 141P-C) accompany the main body. When Don Machholz discovered it in August 1994 its entourage included four icy strays. The comet returns every 5.3 years.

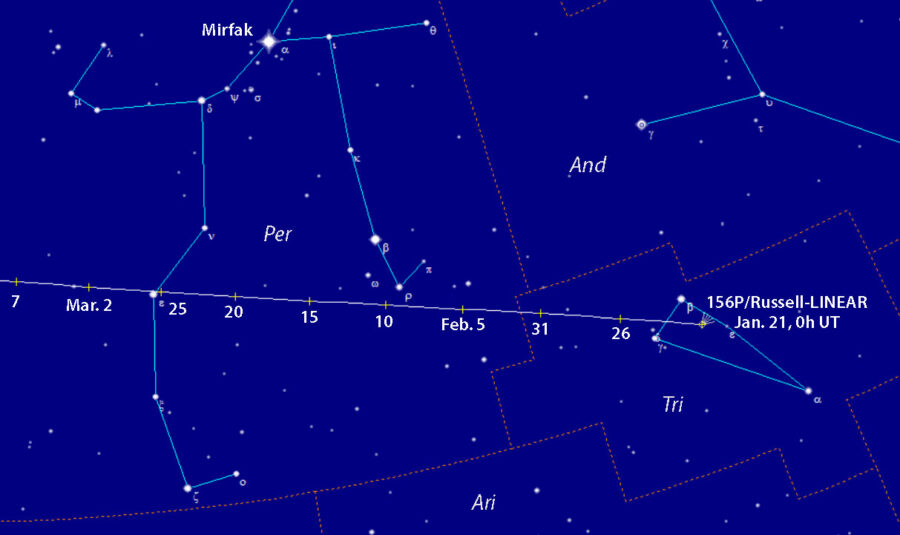

156P/Russell-LINEAR

Evening sky — January to early February

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

Although its magnitude is similar to that of 141P (10.8 on January 8.06 UT) this smaller, more compact comet is easier to spot. For northern observers it helps that it's traversing the high declination terrain of Triangulum and Perseus over the next few weeks. Extra altitude means darker skies. On January 8.06 UT Russell-LINEAR measured about 1′ across with a well-condensed (DC=5) coma and a short, 2.5′ fanlike tail pointing southeast.

Chris Schur

Russell-LINEAR fades slowly in the coming weeks but should remain visible in 10-inch or larger instruments through at least mid-February. The comet's orbital period is 6.4 years.

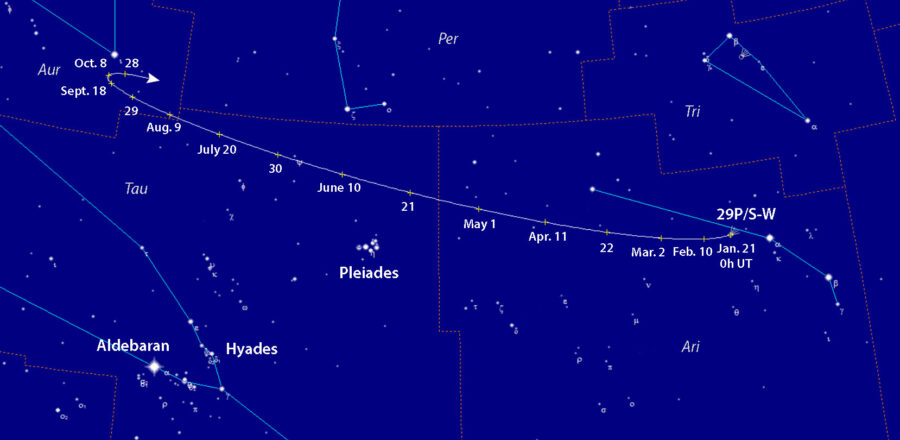

29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann

Evening sky — January to early March then returning at dawn in mid-July

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

This amazing and distant comet undergoes an average of 7.3 outbursts every year with some bright enough to see in a 6-inch telescope. Given that 29P's average distance is around 6 a.u. it's probably one of the most remote comets accessible to amateurs. Normally around magnitude 15–16, I've seen it light up to magnitude 10 more than a few times in the past 25 years. During an outburst this otherwise diffuse object appears tiny and extremely condensed like a bright, compact planetary nebula.

Damian Peach

The origin of its sudden and frequent flare-ups may be eruptions of cryovolcanoes caused by solar heating of subsurface methane ice. The ice melts and absorbs carbon monoxide and nitrogen gases, which liberate enough heat to soften the crust to the breaking point, explosively releasing the pressurized gases and entrained debris. Basically a titanic cometary flatus! Comet 29P's most recent outburst, a fainter one, began on January 14th.

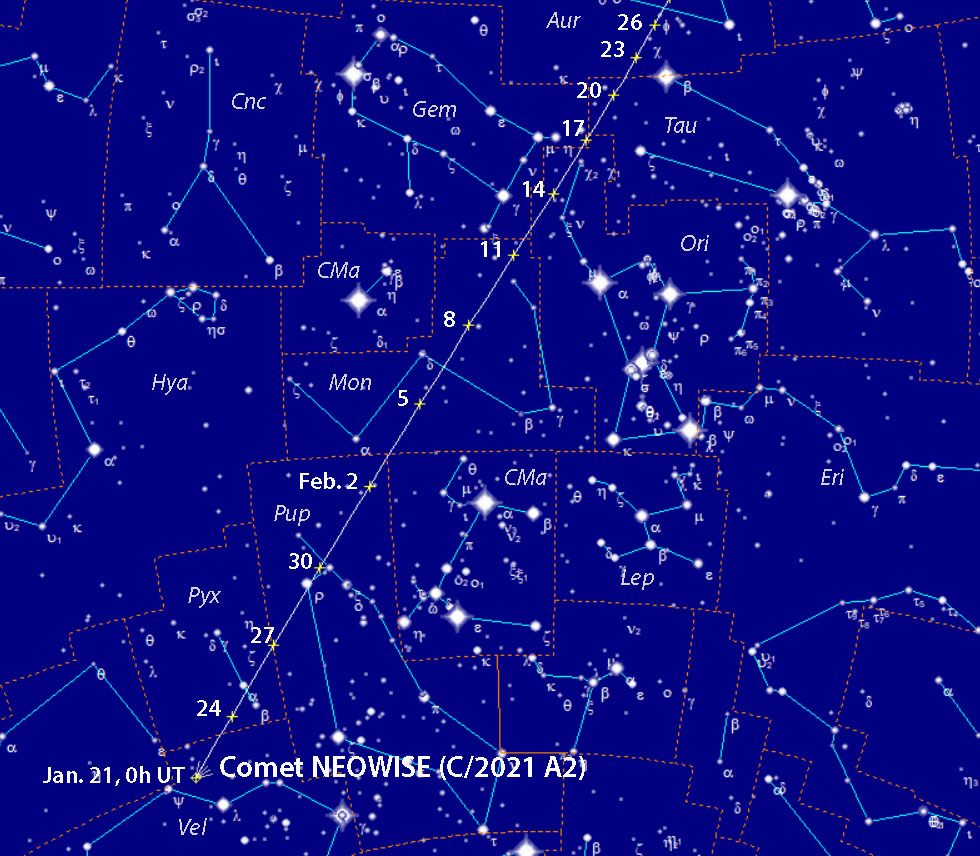

Comet NEOWISE (C/2021 A2)

Evening sky — January and February

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

Discovered at 15th magnitude on January 3rd in photos taken with NASA's NEOWISE space telescope, the comet will reach perihelion on the 22nd and pass closest to the Earth on February 3rd at a distance of 0.5 a.u. NEOWISE is expected to reach a peak brightness of magnitude 10 in mid-February and then fade. On January 7.6 UT Australian comet observer Michael Mattiazzo described the comet as 2′ across and weakly condensed with DC=2. Currently an 11th-magnitude Southern Hemisphere object in Vela, it quickly moves northwest and rapidly gains altitude, becoming visible from mid-northern latitudes later this month.

Michael Mattiazzo

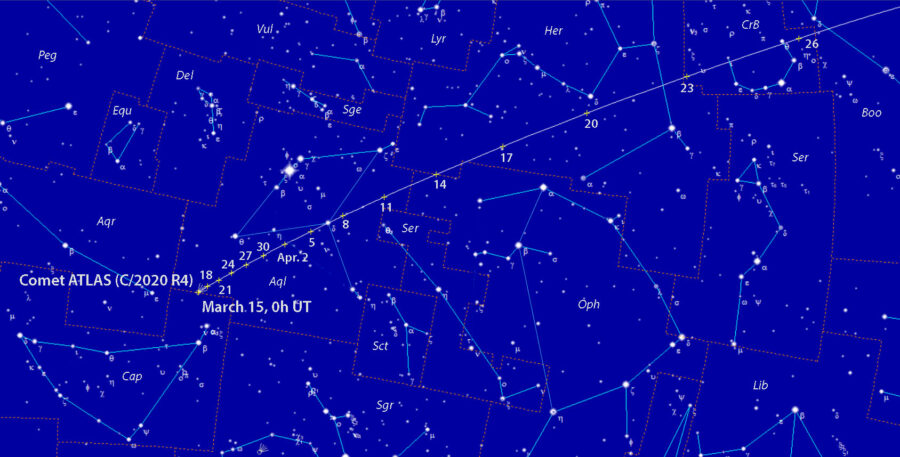

Comet ATLAS (C/2020 R4)

Morning sky — mid-March to mid-April then evenings starting in late April

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

Before disappearing in the solar glare in early January at least one observer spotted Comet ATLAS at magnitude 12, brighter than its ephemeris prediction. ATLAS won't return to view until after its March 1st perihelion when it passes 1 a.u. from the Sun. Our next viewing window begins in mid-March just before dawn. Circumstances slowly improve as the comet heads northwest across Aquila and brightens, reaching magnitude 9 by the third week of April. Closest approach to Earth (0.46 a.u.) occurs on April 23rd. A 6-inch telescope should nab it.

Around mid-April, ATLAS bounds into the evening sky and dashes across Corona Borealis and Boötes while quickly fading.

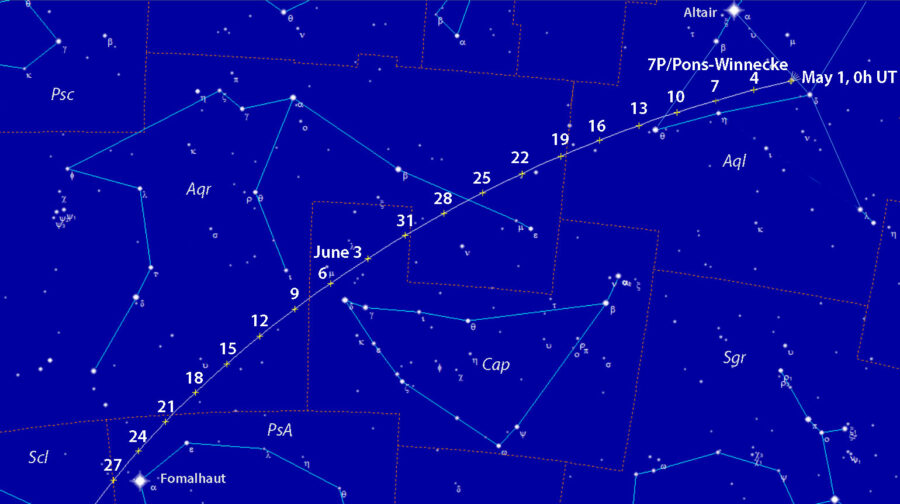

7P/Pons-Winnecke

Morning sky — May through August

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

French astronomer Jean Louis Pons discovered this comet in June 1819, which was then rediscovered in March 1858 by German astronomer Friedrich Winnecke. Comet 7P/Pons-Winnecke belongs to the Jupiter family of comets, short-period comets with orbits primarily determined by Jupiter. Despite returning every 6.4 years I've yet to lasso this critter, one reason I'm looking forward to the current apparition.

Public domain

During 1927's exceptional appearance, 7P passed just 0.04 a.u. from Earth and reached magnitude 3.5. Prior to that, in 1921, early observations suggested the comet might even collide with the Earth in June that year but calculations by American astronomer E. E. Barnard ruled this out.

This time around it only gets as close as 0.44 a.u. (June 12th) and as bright as magnitude 11. Catch this comet from May through August as it wings southeast across the morning sky from Aquila to Phoenix. Northern observers will lose sight of it in early July as it dives into Sculptor. Perihelion occurs on May 27th at a distance of 1.2 a.u., the same time the comet should reach peak brightness.

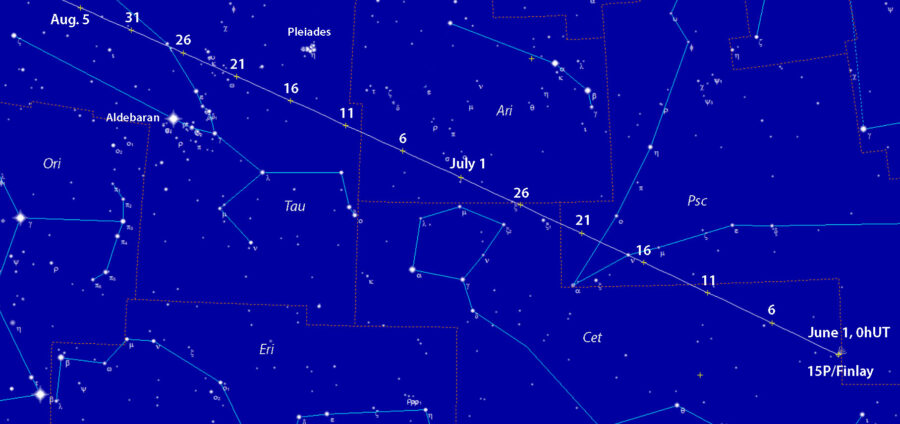

15P/Finlay

Morning sky — May through August

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

Comet Finlay comes around every 6.5 years and returns to perihelion on July 13th at 1 a.u. from the Sun. About a month prior on June 17 it makes its closest approach to Earth of 1.1 a.u. Discovered by South African astronomer William Henry Finlay at the Cape of Good Hope in September 1886, the comet should brighten to about magnitude 10 in mid-July in Taurus low in the northeastern sky just before the start of dawn.

During the previous apparition in 2014–15, the comet underwent two outbursts centered on its December 27th perihelion, first on December 16th from magnitude 11 to 9 and again on January 16th from 9 to 7.5. Might we get lucky again?

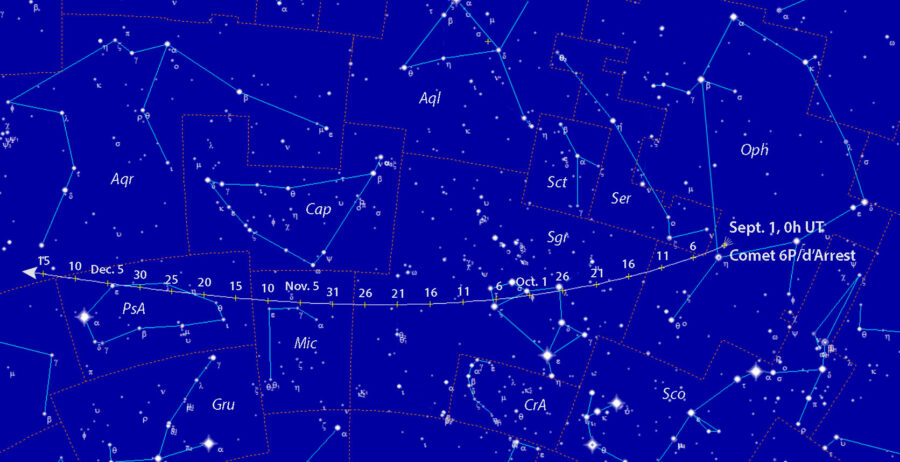

6P/d'Arrest

Evening sky — September to December

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

As summer gives way to fall we welcome another periodic comet — 6P/d'Arrest. Heinrich Ludwig d'Arrest described it as large and faint when he first spotted it in June 1851. The name d'Arrest may ring a bell. He was Johann Galle's student assistant at the Berlin Observatory on September 23, 1846, when Galle became the first person to lay eyes on Neptune. Presumably, d'Arrest was the second.

D'Arrest's comet brightened to 9th magnitude during its 2008 apparition but remained a faint, difficult object in 2015. This time around it arrives at perihelion on September 17th at 1.4 a.u. and passes closest to Earth at 0.75 a.u. on August 2nd. It should have an excellent run in the evening sky into early December and brighten up to about magnitude 10.

Comet Leonard (C/2021 A1)

Morning sky — October through November, then evenings in December

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

Gregory Leonard with the Mt. Lemmon Survey (part of the Catalina Sky Survey) discovered this comet on January 3, 2021 — one year to the day before perihelion — as a fuzzy 19th-magnitude pinhead. But great things often come from humble beginnings. As it heads sunward, Leonard makes a relatively close approach to Earth of 0.23 a.u. on December 13th followed five days later by an exceptionally close pass of Venus of just 0.028 a.u. (4.2 million km) before rounding the Sun on January 3, 2022, at a distance of 0.6 a.u.

While the view from Venus will be memorable, earthlings won't fair too badly. Depending on the source the comet in mid-December could become as bright as magnitude 4 (Seiichi Oshida) or as faint as magnitude 6 according to a recent telegram issued by the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Either way it appears that Leonard could potentially become a naked-eye object as it rapidly crosses from Ophiuchus into Sagittarius low in the southwestern sky at dusk.

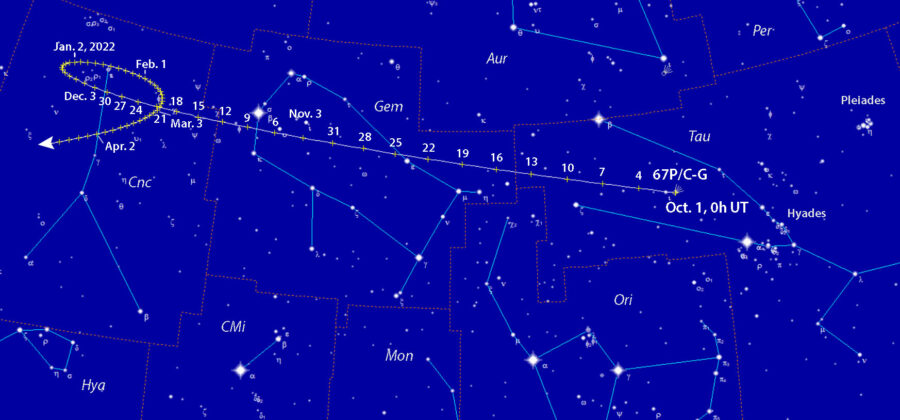

67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

Midnight sky, then evenings — October through February 2022

Chris Marriott's SkyMap

This periodic comet, made famous by the European Space Agency's Rosetta Mission, returns to the inner solar system after a 6.4-year hiatus. This year's apparition is similar to the one it had in 1982, when the comet reached 9th magnitude and grew a pretty tail. Peak brightness occurs from late November through December as C-G heads from Gemini into Cancer. Closest approach of 0.42 a.u. occurs on November 12th.

On the night of perihelion (November 2nd) it's well-placed for viewing, positioned just 3° southwest of Pollux, in Gemini. Back in 1982, watching this comet evolve inspired me to track every future comet within my telescope's reach.

Additional 12–13th magnitude comets that are within reach of 10-inch or larger telescopes under dark skies include two current ATLAS comets, C/2020 M3 (mag. 12) and C/2019 L3 (mag. 13), and 398P/Boattini (mag. 13). Comet 19P/Borrelly will slowly climb into the evening sky later in December and should reach magnitude 9 by early March 2022.

Make a map!

Most comets require a good map to find. Here are several suggestions on how to make one:

- Download a copy of the free sky-charting program Stellarium, available for Windows, Mac, or Linux. Once you open the program and set your location, click on the lower left of your screen to bring up the main menu. Click on the Configuration option icon which looks like a wrench. Scroll down on the left and select Solar System Editor. On the right, click the configure button. In the pop-up window, click Import orbital elements in MPC format. In the import data pop-up, select MPC's list of observable comets or Gideon van Buitenen: comets. Then click the orbital elements button. Close all the little windows and return to the main menu (left side of screen) and click on the magnifying glass icon. Type in the FULL NAME of the comet you're seeking, hit enter, and you'll see it centered on the scree. You can adjust the time as needed by clicking the clock icon in the main menu. Do a frame grab, save, and print out to use at the telescope.

- Head over to Gideon van Buitenen's astro.vanbuitenen.nl for current maps of bright comets. He also regularly updates comet orbital element files for a variety of software programs including Guide, Starry Night, MegaStar, and The Sky. Click and save the comet file over your current comet file to update. I've found his elements and comet lists more current and complete than those at the Minor Planet Center, although the latter will do in a pinch.

- In-The-Sky.org also keeps a list of current comets. Click on the name and then click again to see a customizable finder chart.

4

4

Comments

Chris-Schur

January 21, 2021 at 5:07 pm

Superb article Bob! I too am looking forward to the return of some very interesting comets historically. Dont you just love saying to friends: "Churyumov Gerismenko"...

chris

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 21, 2021 at 9:24 pm

Thanks, Chris! And yes, that's one chewy name 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dan

January 23, 2021 at 5:32 pm

Enjoyed the article!

Check out Dec 8, 2021 when both 15/P and 67/P will be less than 1 degree apart! Hope Finlay holds its brightness at ~1.4 A.U from us and so many months after perihelion.

Love what you do!

Dan Bartlett

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 24, 2021 at 10:56 am

Hi Dan,

Thanks for your kind words. And thank you also for pointing out that close comet pairing. Let's hope 15P hangs in. At least astrophotographers should be able to capture the pair.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.