Astronomers have found 20 new moons circling Saturn — now you can help name them!

Jupiter may be the king of the planets, but — right now, at least — Saturn is the king of moons. Astronomers Scott Sheppard (Carnegie Institution for Science), David Jewitt (UCLA), and Jan Kleyna (University of Hawai‘i) have announced the discovery of 20 new moons circling the ringed planet, putting Saturn’s total at 82 compared to Jupiter’s 79. The moons are each around 5 kilometers (3 miles) in diameter.

The team used the Subaru telescope atop Maunakea, Hawai‘i, to find the moons. Sheppard had previously led a team in discovering of 10 new moons around Jupiter, announced last year, using the 6.5-m Magellan-Baade reflector Las Campanas and the 4.0-m Blanco reflector on Cerro Tololo.

"Using some of the largest telescopes in the world, we are now completing the inventory of small moons around the giant planets,” Sheppard explains. The new discoveries are cool in and of themselves, but ultimately, it’s what they tell us about the solar system’s formation that motivates Sheppard’s search.

Illustration: Carnegie Institution for Science; Saturn image: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute; Starry background: Paolo Sartorio / Shutterstock

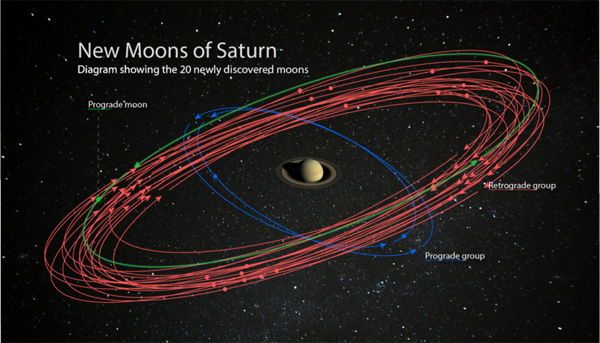

Of the 20 new moons, 17 are orbiting the moon “backwards,” that is, in a direction opposite to the planet’s motion. Astronomers call these orbits retrograde. They’re all at roughly the same distance from the planet, putting them in the Norse group of moons. The Norse group is diverse, but the orbits and inclinations of the newest moons suggest they all originated from the same parent body.

Three other moons are in prograde orbits, two orbiting at an inclination of 46° and one at an inclination of 36°. They belong to the Inuit and Gallic groups, respectively.

See Sheppard’s visual summary of Saturn’s moons here, and peruse Sky & Telescope's catalog of solar system moons old and new here.

Watch a humorous take on the discoveries and what they mean for the moons’ formation here:

Name Those Moons!

You have until December 6, 2019, to tweet your suggested moon name to @SaturnLunacy with the hashtag #NameSaturnsMoons. Describe why you picked the name you did, and include photos, artwork, and videos to bolster your case.

It’s not the Wild West out there — the International Astronomical Union has rules for naming things in outer space, and the moons of Saturn are no exception. Saturn’s moons are named for mythological giants, and which mythology depends on which group the moon belongs to.

Two of the newly discovered prograde moons must be named for giants from Inuit mythology. One moon, which is also prograde but belongs to a different group, is to be named for a giant in Gallic mythology. Likewise, 17 retrograde moons must be named for giants in Norse mythology. Be sure to search the current database of IAU names to make sure the name you’ve picked out isn’t already in use.

Happy naming!

4

4

Comments

Chuck Hards

October 11, 2019 at 11:27 am

At what size does it stop being classed as a "moon", and is just a big piece of orbital debris?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ali Azadegan

October 12, 2019 at 4:59 am

I think they must have diameter more than 500 meters. There is over 150 moonlets between 40 and 500 meters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kevin-Walsh

October 13, 2019 at 6:18 pm

As a result of the Pluto embarrassment, the IAU adopted these Official Classification Schemes:

Planet

Dwarf Planet

Moon

Dwarf Moon

Big Piece of Orbital Debris

Dwarf Big Piece of Orbital Debris

Stuff Stuck In the Bottom of the Vacuum Of Outer Space Bag

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Corey Rueckheim

October 13, 2019 at 2:14 pm

The short answer, in my opinion, is that it would need to be asteroid-sized or planet-sized. Meteoroid-sized objects should not be classified as moons. But now on to the long answer...

This is a question reminiscent of the "what is a planet?" debate. But unlike that issue, I don't believe there is an official definition (flawed or otherwise) that specifies how big an object must be in order to be classified as a moon. If it were up to me, I would use gravity as the deciding factor, as it allows all objects to be categorized in a way that most closely fits our preconceived ideas about what all of these objects are like, and can be determined with scientific data. When it comes to planets and asteroids, if we picture the image of a made-up planet in our minds, it will most likely be spherical (caused by gravity). If we picture an image of an asteroid in our minds, I suspect it will be large but NOT spherical (this time due to LESS gravity). I think gravity is the key to these categorizations.

Objects that are too small for gravity to hold themselves together would be "meteoroids". These objects are held together (in IAU terms "dominated by") the electromagnetic force (chemical bonds, etc.). Next, "asteroids" are larger objects that are (or could be) held together by their own gravity, but the gravity is too weak to pull the body into a spherical shape. Larger still, the pull of gravity on "planets" is strong enough to pull the body into a spherical shape, towards hydrostatic equilibrium. Once an object has enough gravity to begin nuclear fusion, it becomes a "star". Between each of these classes is a fuzzy area that would be difficult to categorize one way or another, but that is a common problem with our artificial classifications in science, and we can come up with methods to solve these problem.

You'll notice that "orbits" do not factor into the definition of meteoroids, asteroids, or planets. To require orbits would eliminate the possibility of including "rogue" or "wandering" objects that have been ejected from their star(s). However, we know these objects must exist, so why not include them in the definitions? I see no logical reason to require orbits in the definitions.

However, you'll notice that by using this method, our Moon would be considered to be a planet. I'm okay with this even if it doesn't fit our preconceived ideas about what the Moon is. However, I'm equally okay if we decided that if an object is a moon, it cannot be considered to be a planet (or an asteroid) but instead would be considered to be a planet-like (or asteroid-like) moon. So what would be a good definition for a "moon" that would fit our preconceived ideas about what a moon really is? This is where "orbits" need to be considered in the definition...

A moon could only be asteroid-sized or planet-sized objects, as any smaller objects (meteoroids) do not fit our conception of what a moon would be. For any object to be a "moon", it would also need to be "in orbit" around another asteroid-sized or planet-sized object, meaning that the barycenter (center of gravity) for the two object system would need to be beneath the surface of the moon's "host" object. For example, the barycenter of the Earth-Moon system lies approximately 1,600 kilometers beneath the surface of the Earth, making the Moon a true "moon" of the host Earth. The Pluto-Charon system, on the other hand, would be different. The barycenter of the Pluto-Charon system lies is space between them, above the surface of both, making this a double planet system, rather than a host-moon system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.