Explore NASA’s rich image archive and discover the solar system as you’ve never seen it before.

It’s been 55 years since Mariner 4 took the first up-close photos of Mars. Since then, a fleet of unmanned spacecraft have followed, photographing in detail every planet of the solar system, along with Pluto and scores of moons, comets, and asteroids. Landers and rovers have imaged the sands of the Red Planet, orbiters have pierced the clouds of Saturn’s moon Titan, and robotic explorers have flown through the shadow of Neptune. More than a few volcanoes, geysers, storms, rings, and craters have been found in surprising places.

Collectively, these probes have returned millions of photographs. Because of the sheer amount of data, it’s only natural that the images have been curated. The very best of them have been processed, polished, and reproduced in books, magazines, and on the web. Some of the photos have been reproduced so often that they’ve become icons of a particular mission. Perfect examples of this are the Voyager 2 approach photos of Uranus and Neptune, the New Horizons’ “heart” image of Pluto, and some of the Viking Mars lander “frost” photos.

NASA / JHUAPL / SWRI

It may surprise some space enthusiasts to learn that the rest of the photos from these spacecraft — not just some, but generally all of the photos — are available and easily accessible to the public, thanks to the Planetary Data System (PDS), a NASA archive dedicated to the ongoing collection and preservation of data from unmanned planetary probes. Here we’ll focus on the PDS image archives, though the site also houses other types of spacecraft data, such as cosmic ray measurements, trajectories, atmosphere data, and magnetic fields.

Find an in-depth overview of handling the PDS data platform and image-processing in Emily Lakdawalla’s feature article in the May 2018 issue of Sky & Telescope.

With very few exceptions, the PDS includes just about everything you can think of: outer-planet missions like the Voyagers, Galileo, and Cassini, inner-planet flights to Mercury and Venus, and of course, the multitude of Mars missions. Thousands of images are there for anyone who’s looking for them — and many of them have never been published.

Exploring a Unique Perspective

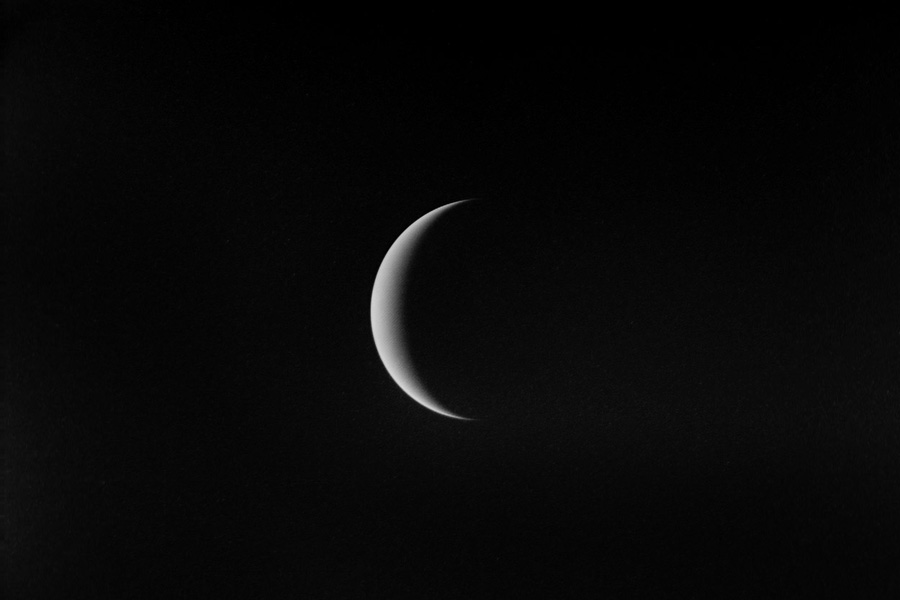

Diving into these archives gives you a chance to explore more deeply the nuances of a particular mission and its target. You can truly get a feel for the spacecraft’s trajectory and what it might be like to experience a given world from that viewpoint. Over the course of consecutive photos, you can watch a target grow larger and larger as the spacecraft approaches its target world until the view fills the frame, then finally the probe passes behind the target and photographs a crescent view — a view generally impossible to witness from Earth.

Also fascinating are photos that have not undergone any processing or enhancing, the so-called “raw” images. You can see what the images look like “straight out of the camera,” complete with imperfections like data dropouts (where portions of the image are represented as black pixels) and motion blur.

Daniel Johnson

Daniel Johnson

There might be multiple “outtake” versions of a familiar shot — instances where the composition was a little off and something critical was cut out of the frame. Operating cameras remotely when separated by millions of miles is challenging! In fact, considering the difficulties involved, it’s incredible to discover just how good most of the photos are.

Many photos you see will seem to be black-and-white — but don’t be fooled. While some spacecraft cameras do produce greyscale images (like the navigational cameras on the Curiosity rover), many of the color pictures you see published are actually a composite of greyscale images taken through individual color filters.

A Processing Challenge

One of the most exciting things you can do with the image archives is to process the photos yourself, using imaging-editing software.

You might also want to download a (free!) copy of the NASAView image display software. While fairly basic, NASAView will permit you to open and view some of the uncommon file formats — including the raw versions — that you’ll find inside the PDS. Find NASAView here.

The archives give you the opportunity to explore real science data for yourself. To produce this color image of Jupiter, I used the PDS Ring-Moon Systems Node's OPUS search service to find a Voyager 1 Jupiter portrait that I liked. I selected three similar frames, each taken within a few moments of each other, and each with a different color filter: violet, green, and orange. I then used photo processing software to combine each of these greyscale images into a single image, with each filter on a different color channel. The result is a color RGB image. (The Voyagers didn’t carry true red filters, but the orange functions as a fine approximation).

Daniel Johnson

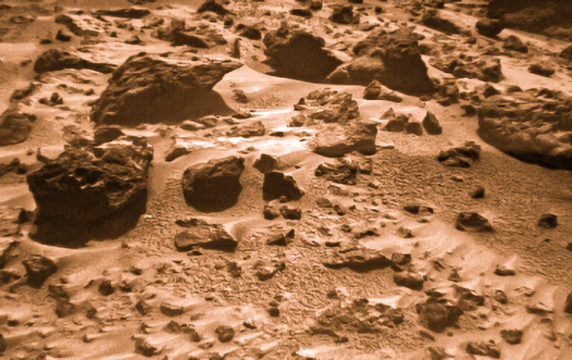

Browsing the Mars Pathfinder archives, I found two images of rocks and windblown sand taken in 1997 from the small Sojourner rover. In this case, the images really are greyscale—and also quite small. To process them, I stitched both images together, and then increased the resolution by using a smart-upscaling algorithm in my photo editing software. Because I’m processing strictly for aesthetic purposes (and not science), my goal is just to create an end-result that looks nice, so I also chose to colorize the final image.

Daniel Johnson

Final Thoughts

While the PDS houses copies of all planetary probe data, current missions (Curiosity, InSight, and others) may also provide lightly processed “raw” files on the mission’s webpage. New photos are generally added to these pages within days or even hours after they are taken, so it’s an excellent way to stay up-to-date on what the probe is doing.

The main takeaway? There are — literally — entire worlds in the PDS archive, completely free and just waiting for you explore them. Are you up for the challenge?

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.