The first-ever planetary defense mission is now on its way to the asteroid Didymos and its moon, Dimorphos.

Last night, a spacecraft built during the hardships of the COVID pandemic successfully departed Earth on a one-way trip to an asteroid. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, launched November 24th at 1:21:02 EST and will crash into Dimorphos, the moon of asteroid 65803 Didymos, in September or October 2022. This isn’t an asteroid science mission — it’s the first ever planetary defense mission.

NASA's DART mission darts up through the clouds, starting it's 10 month journey to impact asteroid Dimorphos.

— Oliver Pelham Burn (@opbphotos) November 24, 2021

Photo by me for @SuperclusterHQ pic.twitter.com/Oi6ZEGgg4b

Beautiful launch of NASA’s DART mission aboard Falcon 9 as seen from Santa Ynez, CA.@NASASpaceflight pic.twitter.com/0xOVOenmJQ

— Pauline Acalin (@w00ki33) November 24, 2021

Gianluca Masi caught DART on its outbound trajectory, the booster that carried it there tumbling behind it. Take a look at an animation of the Virtual Telescope's images:

Gianluca Masi / Virtual Telescope

“Planetary defense” refers to discovering, and then mitigating, threats to our planet from potential comet and asteroid impacts. In any given year, the probability of an asteroid impact in a populated area is extremely low compared to the probability of other kinds of natural disasters. There’s no asteroid currently known to be on a collision course with Earth at any time in the foreseeable future. But what we don’t know could hurt us: If a big-enough asteroid is in the wrong place in the wrong time, it could destroy a city, threaten human civilization, or even cause a mass extinction.

Fortunately, impacts can be predicted, if we discover potentially hazardous asteroids early enough, and then the hazard can be mitigated, at least in theory.

The most powerful way to remove the threat of a potentially hazardous impactor is to track the asteroid. A 1-in-1,000 chance of an impact almost always turns into zero likelihood of impact once astronomers have determined the asteroid’s path with greater precision. But if tracking an asteroid reveals that it is even more likely to crash into us, there are other options.

We can move people out of the way of the hazard or — better yet — redirect the asteroid itself, moving it away from its dangerous path. However, nobody has ever redirected a space rock before. Engineers have proposed a wide range of possible methods to alter the path of an asteroid enough to prevent an impact, but none has been tested in practice. Such testing has to be done carefully, when you’re talking about near-Earth asteroids: What if your test goes in a way you don’t expect and actually increases the risk of a future impact?

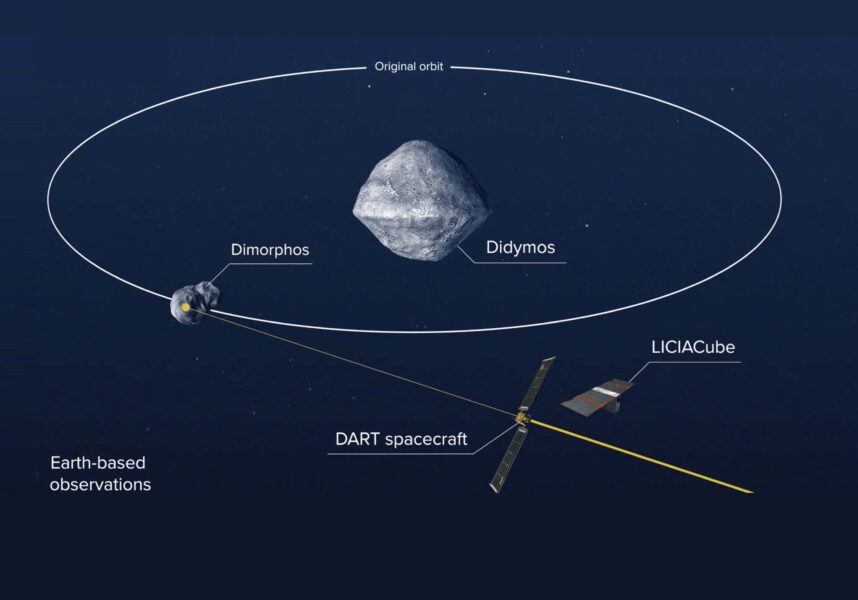

ESA

DART will test a low-tech method for altering an asteroid’s path in a way that can’t possibly increase the threat to Earth. The spacecraft that launched today will fly to the near-Earth asteroid Didymos. Altering its orbit would have a tiny but real risk of increasing the risk to Earth. So we’re going to leave Didymos alone. But Didymos has a small moon, discovered in 2003, named Dimorphos.

DART will crash head-on into Dimorphos. If DART and Dimorphos were billiard balls of infinite strength and elasticity, the outcome of the impact would be easy to predict: the spacecraft would bounce off almost as fast as it hit, and the moon would slow by a tiny amount. But Didymos and Dimorphos are almost certainly rubble piles, which are not bouncy like billiard balls. They’re loosely agglomerated piles of gravel with a lot of empty space. What happens then?

On one hand, the lack of cohesion among the particles might allow the swift-flying spacecraft to penetrate deeply into the surface, compressing it instead of bouncing off. That would reduce the effectiveness of the collision.

On the other hand, the energy DART imparts will mobilize Dimorphos particles, launching them off of the super low-gravity asteroid moon. Each fragment will carry some of Dimorphos’ momentum with it. The slowing effect of flying ejecta is predicted to rival the slowing effect of the head-on impact.

NASA

Shortly before DART arrives, an Italian-built cubesat named LICIACube will separate from the carrier craft. Then DART will autonomously steer to a high-speed crash into Dimorphos, ending its existence. LICIACube will watch the impact, observing the spray of ejecta.

The death of the DART spacecraft is when the science begins. The impact will happen when Didymos is relatively close to Earth, making it an easy target for both optical and radio telescopes. Back on Earth, astronomers will watch Didymos, carefully measuring the changes in brightness, or light curve, of the pair to measure Dimorphos’s orbital period around Didymos. If scientists’ models are correct, the impact should change Dimorphos’s period by several minutes.

Whether the models are correct or not, we’ll have performed the first-ever experiment in changing an asteroid’s velocity, and we’ll have learned valuable lessons toward that inevitable time in the future when we need to move an asteroid intentionally away from a population center.

3

3

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

November 24, 2021 at 3:59 pm

Thanks for explaining why redirecting the smaller asteroid in a binary pair is a safe way to test this technology.

We have a much more urgent need to defend our planet from human greed and stupidity. And anyway, asteroid impacts aren't all bad. If the dinosaurs had a planetary defense system, we mammals would still be cowering in burrows and treetops.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

relh

November 26, 2021 at 5:11 pm

I know my question might appear simple to some, but doesn't the collision affect the momentum (however small) of the Didymos/Dimorphos system as a whole? I'm not worried about the future because of this test, but the momentum change in the system as a whole has to go somewhere.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

StanR

November 27, 2021 at 1:06 am

@relh I had much the same question. If the collision were to be inelastic (nothing leaving the system) one would think it wouldn't matter which object was struck since all three objects would continue together through space with the sum of the momentum vectors. I suspect it's not about "safety" but rather about having an effect that's easier to measure.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.