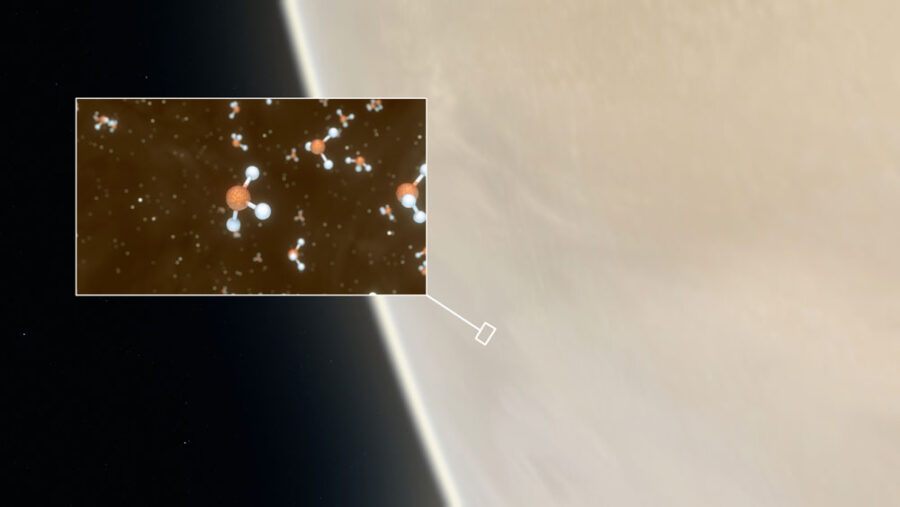

Astronomers might have found a potential indication of life in the clouds of Venus.

ESO / M. Kornmesser / L. Calçada & NASA / JPL / Caltech

An international team of researchers led by Jane Greaves (Cardiff University, UK) has announced the detection of phosphine in the relatively cool cloud decks of Venus.

Phosphine is a trace gas in Earth’s atmosphere associated with anaerobic life. Astronomers have previously observed it on Jupiter and Saturn, but its production there is understood to be driven by the gas giants’ high pressure, hydrogen-rich environments, and intensely hot depths. On Venus, it could be a sign of something else entirely.

As reported September 14th in Nature Astronomy, Greaves and her colleagues observed Venus first with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in 2017, then again with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in 2019. They observed the planet at millimeter wavelengths and found the chemical fingerprint of phosphine — a molecule that many think could be a biosignature, or sign of life.

The team investigated numerous possible abiotic sources for the molecule in Venus’s atmosphere, including geological activity, meteorite impacts, and lightning. None of these scenarios could account for the phosphine they had found in the atmosphere.

If the detection pans out, it might be a sign of life on our sister planet.

From Toxic Gas to Biosignature

ALMA (ESO / NAOJ / NRAO) / Greaves et al. Nature Astronomy, 2020 Sept. 14th.

“Back in 2016 I was going through old solar system literature and I came across the detection of phosphine on the gas giants,” Greaves says. “I thought, ‘Whatever is this molecule?’”

On Earth, this molecule is mostly produced industrially, but microbes can make it too. Greaves was aware of the theory of aerial life on Venus, and she realized that she might actually be able to see a certain transition from telescopes on the ground.

“No one had thought to look for phosphine there before,” she says. “When we discovered it, I was shocked!”

In its pure form, phosphine is a colorless, odorless gas made up of one phosphorus atom and three hydrogen atoms. It is flammable at room temperature and highly toxic, which is why it is produced mainly as a fumigant and occasionally used as a chemical weapon.

But it was also shown to be a naturally occurring part of Earth’s anaerobic biosphere by Dietmar Glindemann (University of Leipzig) in the 1990s. His research led to the discovery of phosphine-producing microbes. In 2013, scientists of the All Small Molecules (ASM) project, led by Sara Seager (MIT), decided to include phosphine in their search for potential indicators of life on other worlds.

Quantum chemist Clara Sousa-Silva joined the effort in 2015, researching its potential as a biosignature gas on rocky exoplanets. It was this work that eventually caught Greaves attention; the MIT theorists and Greaves’ group of observers finally joined forces in December 2018.

The spectral transition that Greaves observed with JCMT and ALMA is by far the easiest phosphine line to see from Earth. Looking into Venus’s atmosphere is not easy, as it is close, large, and bright. Phosphine absorbs radiation from lower in the atmosphere at a wavelength of 1.123 millimeters. The molecule should absorb other wavelengths as well, but they are at frequencies not easily accessible from the ground or from current space telescopes.

Anita Richards (University of Manchester, UK), the team’s ALMA liaison, helped Greaves to reduce the ALMA data. “Venus appears almost as big as the entire field of view of ALMA,” Richards explains. Identifying the signature caused by phosphine required an intricate process of data processing that took four months.

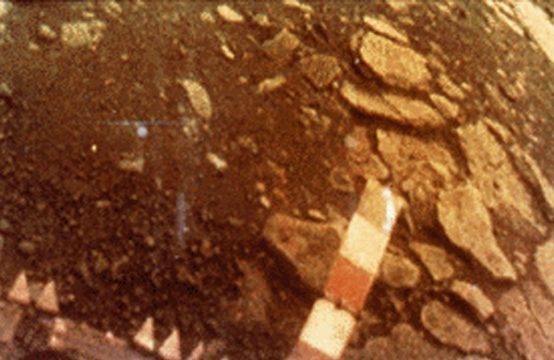

So, Is There Life on Venus?

NASA History Office / Roscosmos

David Grinspoon (Planetary Science Institute), an expert on Venus who was not involved in the project, says that the result will be contentious, in part because the discovery is based on a single absorption line.

“People will look very critically at this. As they should,” Grinspoon said. “We don't want to jump to the wrong conclusion about something this important.”

The team is confident in the analysis but agrees that independent observations are needed to detect other phosphine absorption lines in order to verify the detection. As for whether the phosphine on Venus is a biosignature, they’re agnostic.

“My gut tells me an unknown photochemical process is going on,” says team member William Bains (MIT). “I think the chances of there being life on Venus are very small.”

Coauthor Sousa-Silva is similarly cautious. “My science tells me the detection is true, but it's pretty wild,” she says. “I hope that everyone will get their models running and try and find alternatives that explain this. I have reached the limits of my knowledge and welcome the rest of the scientific community to join in the fun.”

7

7

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

September 14, 2020 at 2:39 pm

According to the National Library of Medicine PubChem database, phosphine has the disagreeable odor of garlic or decaying fish.

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Phosphine

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John-Murrell

September 14, 2020 at 4:52 pm

From what it says elsewhere the smell is the result of impurities in industrial quality gas. The pure form cannot be smelt and just kills you.

It could be that the commercial gas is deliberately given a smell to provide some warning if people get into areas that are contaminated by the gas typically after it is used for fumigation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

September 14, 2020 at 7:39 pm

Thanks John. The wikipedia page on phosphine states:

"Pure phosphine is odorless, but technical grade samples have a highly unpleasant odor like garlic or rotting fish, due to the presence of substituted phosphine and diphosphane (P2H4)."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phosphine

I guess we're still waiting to learn if ALMA found any organophosphines (i.e. substituted phosphine) or diphosphane in the Venusian atmosphere.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

September 15, 2020 at 12:44 pm

Ockham's razor.

The Trac II model...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David-Stoltzmann

September 18, 2020 at 4:16 pm

As reported September 14th in Nature Astronomy, Greaves and her colleagues observed Venus first with the James Clark Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in 2017

James CLERK Maxwell Telescope!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joseph-Shuster

September 18, 2020 at 6:30 pm

They should have telegraphed their results.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica Young

September 18, 2020 at 7:53 pm

Thank you for pointing this out, typo is fixed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.