A new computer simulation provides a brief glimpse at what makes stellar bombs tick.

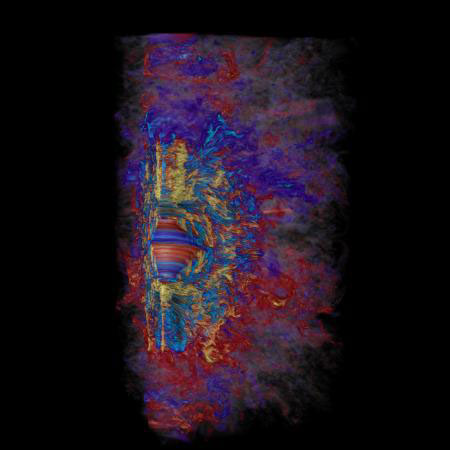

Moesta et al. / Nature

It’s hard to make a star explode. Within Blue Waters, one of the most powerful supercomputers in the world, 130,000 computer processors worked around the clock for 18 days to simulate the supernova of a star six times the Sun’s mass. The result? 10 milliseconds of swirling gas that gives an all-too-brief window into the magnetic mechanics of stellar blasts.

But even in that glimpse, Philipp Mösta (now at University of California, Berkeley) and colleagues managed to replicate not only the explosion itself but also the enormous magnification of the star’s magnetic fields that happens in the process ¾ the fuel behind some of nature’s most violent blasts. The team reported the successful supernova simulation on November 30th in Nature.

Modeling the Rarest Supernovae

NASA / Dana Berry / SkyWorks Digital

Astronomers see supernovae all the time: one star explodes every 50 to 100 years in a galaxy like the Milky Way, and there are more than 100 billion galaxies in the universe.

But not every supernova’s the same. On rare occasions (perhaps every 100,000 to 1 million years in a Milky Way-type galaxy), a massive, rapidly spinning star collapses. When it does, it emits a several-second blast of high-energy photons known as a long gamma-ray burst.

Modeling these rare and mysterious beasts is a tricky business. In a core-collapse supernova, the dying star’s rapidly spinning iron center falls in on itself so quickly that it bounces, sending a reverse shock wave into the star’s outer layers and expelling them with explosive force. Previous calculations of this complex process have often been limited to global 2D simulations or 3D simulations of only small portions of a star. But when Mösta’s team attempted global 3D simulations a year ago, they couldn’t get the star to explode.

The moments right after the iron’s core collapse make or break the supernova. So this time around, Mösta and colleagues watched the supernova at incredible resolution. And rather than fix the magnetic field, as they had done in 2014, they let it evolve naturally.

As the 10 milliseconds unfolded, Blue Waters’ 130,000 processors tracked the effects of general relativity, neutrino-matter interactions, and radiative physics, among other things. Through it all, they also for the first time tracked the growth of magnetic fields. And these fields, it turns out, may be the key to exploding a star.

Magnifying Magnetism

In a rapidly spinning star, the center rotates faster at its center than at its outer edges. A magnetic field that gets caught between two differently rotating layers will get stretched out, growing quickly in strength. This simple idea isn’t new — Steven Balbus and John Hawley outlined the mechanism back in 1991. But Mösta’s team is the first to show the effect at work within a global 3D supernova simulation, where it roughly doubles the magnetic field every 0.5 millisecond before the star's dynamo action takes over. Within moments, a magnetic field a million billion times the Sun's has formed.

The key to this simulation's success is resolution. Not only do the simulations track changes throughout the star, they also visualize the results with a sharpness down to 50 meters, discerning plasma bits about the size of the Space Shuttle. Only in the highest-resolution simulations does the magnetic field grow into a writhing beast enfolding the crushed stellar core — watch the video below to see it happen (yellow represents positive magnetic fields and light blue shows negative fields; red and blue represent weaker positive and negative magnetic fields, respectively).

This magnetic engine is what helps expel the star’s outermost layers and probably drives a jet out along the star’s poles. “This means that we have another reason to believe that strong magnetic fields in collapsing stars are driving the jets that produced gamma-ray bursts,” says supernova expert Brian Grefenstette (California Institute of Technology).

But the quest to simulate a supernova isn’t over yet. The central neutron star doesn’t cool and stabilize until tens of seconds after the explosion, says study coauthor Roland Haas (Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, Germany), and the shock wave continues to ripple through the outer stellar layers long after that.

“What no one so far has done is follow the entire supernova explosion until it breaks out of the star,” says Mösta. “We are working toward this, but the timeline realistically is probably 1 to 3 years.”

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.