Street lights contribute to light pollution, but they are far from the only culprits — and fixing street lights is far from the only solution.

Falchi, et. al

Millions of artificial lamps brighten our cities every night — but only part of their light is used to actually illuminate streets, sidewalks or billboards. The rest is lost, emitted above the horizon and serving no other purpose than to brighten the night sky.

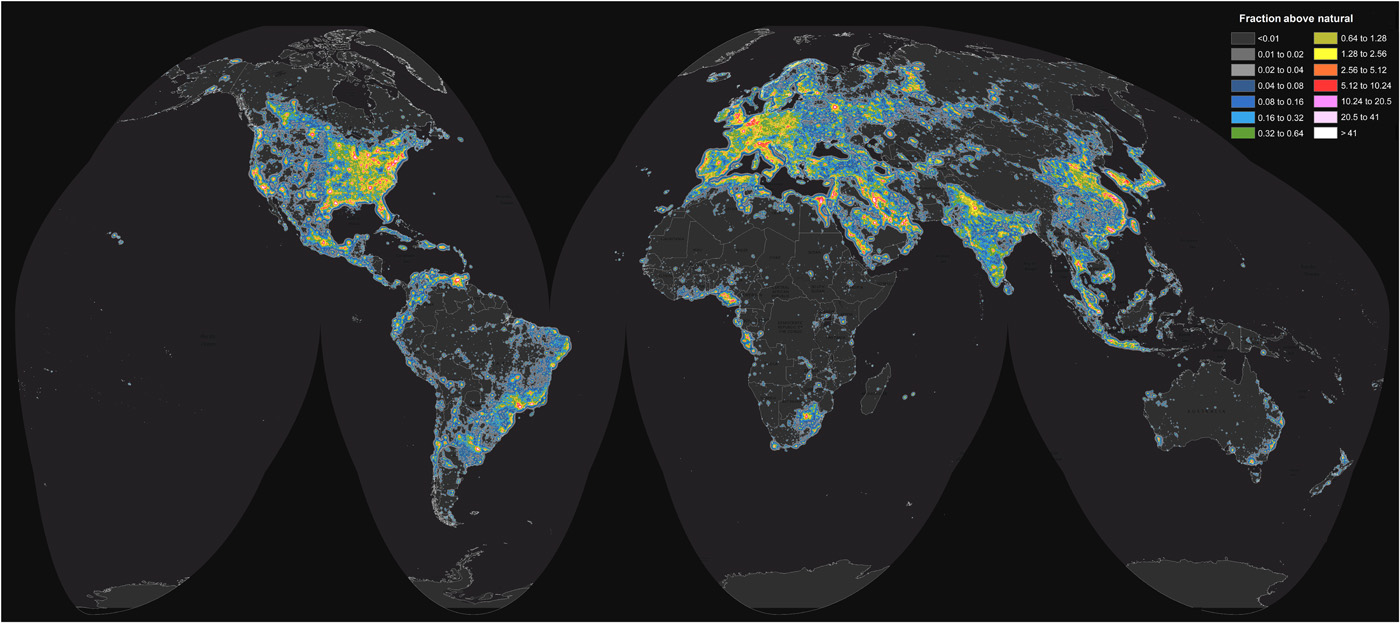

Satellites like the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP for short) have mapped the extent of artificial light around the globe, revealing that more than 99% of the U.S. population live under light-polluted skies. The Milky Way is hidden from nearly 80% of North Americans.

Wasted light also means wasted energy, greenhouse gases, and money. Reducing it should be a matter of course, even for those who don’t care about bringing back the stars to suburban and city skies. But to focus their efforts, policy makers need to understand where unwanted light is coming from.

Now, scientists have found an important new lead on light pollution.

Streetlights Are Not the Only Culprits

Researchers have long pondered about the fraction of street lighting that contributes to light pollution, with figures ranging wildly between 12% to more than 80%. Thanks to Kyba’s unique experiment, they now have a more reliable number.

“Streetlights are a very important source of light for a city, and maybe the most important single source,” says Christopher Kyba (GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences). “But they are actually not the main source. At least for a city that has a very well-designed street-light system, most of the light is coming from other sources.”

In 2017, the city of Tucson, Arizona, converted more than 19,000 municipal street lights to LED and combined them with a “smart city” lighting control system, which allows every single one to be monitored and even dimmed. From March 29 to April 7, 2019, Kyba and an international team of colleagues worked with Tucson’s advanced system to carefully dim and brighten the public lighting network over several nights. They then imaged the city every night using Suomi’s Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite, an instrument designed to capture visible and infrared light coming from Earth.

GFZ

Surprisingly, they found that the street lights contributed only 20% to the light escaping into space. The other 80% comes from other light sources, such as parking lots, malls, garden lights, illuminated building facades, and billboards.

It should be noted that Tucson, motivated in part by nearby astronomical observatories, uses fully cut-off shielding for their street lights, ensuring that none of the lamps’ light spills into the sky. This gives Tucson darker skies than most cities.

Nevertheless, Kyba says, the question becomes, “when we fix street lights, is light pollution basically solved? Our paper suggests that actually no, we are very far away from solving the problem.”

The result, published in Lighting Research & Technology, will therefore have consequences for attempts to reduce skyglow and light pollution.

Ground Truth

Satellites detect only light beamed towards the zenith. But most skyglow comes from light emitted towards the horizon, which then scatters off of aerosols and air molecules. Space-based data therefore need to be compared to ground-based data.

Indeed, observations of sky brightness, performed in parallel by John Barentine (International Dark Sky Association) and colleagues confirm Kyba’s conclusions.. Using commercially available Sky Quality Meters, DSLRs, and light meters, Barentine's team found that Tucson’s street lights contribute only about 14% to the city’s skyglow.

John Barentine

For example, when the scientists dimmed the street-light system from 90% of its full power draw to 30% after local midnight, zenith sky brightness decreased by only 5.4%. Even on nights when the power output was instead increased to 100%, sky brightness still decreased slightly, apparently because private lighting was shut off after midnight. The results are published in the Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer.

How to Reduce Light Pollution

From their combined research, the scientists draw three major conclusions:

First, changing streetlights to full-cutoff LEDs and dimming them after midnight certainly helps. But it’s not enough. “The next thing is to understand other types of lighting,” says Kyba. “How much is coming from signs, billboards, security lighting, illuminated facades or ‘vanity lighting projects’, etc.?”

He suspects that billboard advertising plays an important role, at least in larger cities, because they tend to intentionally direct light towards the horizon. “They punch above their weight in some sense, and I think it is quite important to consider them in local planning.”

Second, satellites can determine major sources of light pollution and help policy makers to efficiently direct resources — especially if validated by measurements from the ground. Any city that has dimmable streetlights and a control system is able to undertake the same experiment. Indeed, the researchers followed up with similar studies in Ireland and Germany, which have confirmed the results found in Tucson.

Third, based on this follow-up, the researchers found that many cities have trouble with their systems. In some cases, the lights did not dim as programmed; in others, they returned false data. “Control systems for dimming could really use a little more standardization or more tools to be added in order to allow cities to do things right,” Kyba says.

It’s very likely that results will vary from one place to another, the authors note. In small towns, public street lights may make up a much larger portion of total emissions. Also, the color of their light affects their contribution to skyglow. White-light LEDs emit a larger amount of short-wave blue light, which is scattered more easily in the atmosphere.

While more research is needed to further investigate the effects of each individual lighting group, Kyba urges that there is no reason not to start tackling the problem right now. In the end, every photon used to illuminate the atmosphere is wasted — and every well-shielded lamp, dimmed to just the right amount of light, brings back a little bit of the starry sky.

3

3

Comments

Gerald-Hanner

November 3, 2020 at 2:06 pm

Ann Arbor Michigan has some of these darkest streets I have ever encountered, yet the parking lots, especially around shopping centers, really do wash out the night sky.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John

November 6, 2020 at 4:34 pm

I'm within a mile of several car dealerships and I'm unable to use RGB imaging except on very rare occasions - only NB for me! And our humid atmosphere doesn't help, either.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Cornelis-Deering

November 7, 2020 at 6:27 pm

Why not implement the light source with a dimmable radio frequency or other type of transmission in the light emitting source in itself and dim the lights from space by satellite.

Invent a new light source!

CaseyD

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.