The beloved Perseid meteor shower of the August vacation season will evade the moonlight in 2024, at least during the best early morning meteor-watching hours. The Lyrids and Geminids aren’t so lucky.

Of all the many celestial sights visible around the year, meteor showers seem to captivate public interest more than most. It's clear why. On a quiet, dark night under the stars, it catches you by surprise when a bit of space rock creates the sudden dash of a shooting star as it tears into the top of Earth's atmosphere ― ending its life in a moment before your eyes after ages in space.

Moreover, annual meteor showers are fairly predictable, coming at about the same times each year.

But like most else in amateur astronomy, meteor observing goes best with patience and foreknowledge.

What Are Meteors?

A meteor is the streak of light you see when a bit of interplanetary debris vaporizes as it rips into Earth's upper atmosphere at a speed of, usually, 30 to 70 km per second (20 to 45 miles per second). Although some meteors look so bright you could almost touch them, they occur at altitudes of 80 to 120 km (50 to 75 miles).

Meteors are common. If you gaze steadily into a dark, moonless night sky somewhere far from city lights, you'll likely see a sporadic (random) meteor a few times per hour throughout the year. But showers bring the main action.

Meteors range in brightness from tiny flicks just at the limit of visibility to dramatically bright fireballs that outshine Venus and maybe even light up the landscape around you. The rarest of these, called a bolide, shatters explosively into pieces during its descent and, if it penetrates deep enough into the atmosphere, can create a boom or rumble that reaches you a minute or two later. Those are once in a lifetime events.

J. Kelly Beatty

Because they arrive so fast, even small meteor particles produce a lot of light. Typically they're no bigger than large sand grains or tiny pebbles. Something the size of a pea can create a meteor that's dramatically bright. Those high velocities give each little particle a lot of kinetic energy, which converts to heat and light due to air friction and shock heating in the upper atmosphere. Many people think a meteor occurs because the particle "burns up." But actually, as the particle vaporizes, the shock wave spreading away from it heats air molecules to thousands of degrees. The air molecules usually cool in a split second, giving off light as they do. (The in-depth explanation.)

What Is a Meteor Shower?

Most meteor particles (they're called meteoroids when still in space) are bits of debris that were shed by comet nuclei crumbling when warmed by the Sun. The debris continues along the comet's orbit, eventually spreading all around the orbit and out to the sides as well. Whenever Earth, in its own orbit, passes through one of these sparse streams of grit, the result is a meteor shower. Some sporadic meteors are from old meteor streams that have spread out and lost their identity; others are rockier debris from old asteroid collisions.

During the half dozen strongest annual showers, under a dark sky you may see something like 20 to 60 meteors or more per hour late at night. Some showers last just a few hours. Others, older and more diffuse, last for weeks.

Keep watch for at least a half hour during one of the stronger showers, and you'll notice something: Not only are meteors more frequent than usual, they appear to fly in directions away from a particular point in the sky. That point is called the shower's radiant. It's the perspective point where all the shower members (which are flying in parallel) would appear to come from if you could see them approaching from far away in space, instead of in just the last second or so as they enter the atmosphere. They can appear anywhere in your sky. But their paths, if you trace them backward far enough, all intersect the radiant spot.

To get a better sense of the picture, check out the interactive meteor-stream animations created by Ian Webster. The one below shows particles spread out around the orbit of Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, the comet responsible for the Perseid shower. (Have some fun with it: Click and drag the animation to get different perspectives, or go to meteorshowers.org to try a different shower.)

(Note: Most of the actual meteor streams are somewhat narrower than displayed; the animations are based on meteor directions and speeds measured from the ground, and slight measurement errors broaden the 3D paths shown in space.)

Meteor Shower Radiants

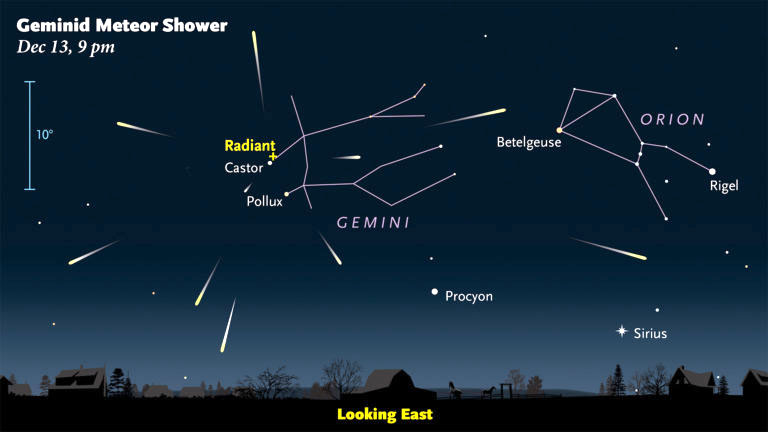

A shower usually gets its name not from its parent object but from the constellation where the radiant lies. For example, August's well-known Perseid shower has its radiant in Perseus, and December's Geminids appear to radiate from Gemini. One notable exception is the Quadrantid shower, named for the now-defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis. Its radiant is in northern Boötes.

Sky & Telescope

The higher the shower’s radiant is in your sky, the more nearly straight down the meteoroids arrive, and thus the more you'll see in a given area of sky. When the radiant is low, we see few. When the radiant is below your horizon, no shower members appear at all.

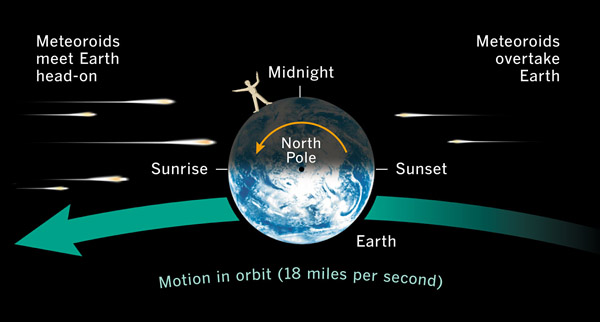

Meteor showers are usually at their best after midnight, because most radiants are highest in the hours before dawn. The graphic below shows why: Morning is when you're on the side of Earth facing forward along Earth's orbit. We circle the Sun at about 30 km (18 miles) per second, so interplanetary debris slams into the morning sky especially fast, making each meteor brighter than it would be if it had hit in the evening, when it would be catching up to Earth from behind.

Sky & Telescope

Think of raindrops hitting your car's windshield. If the car is moving forward, the drops hit harder and more plentifully. In addition, the radiant of the raindrops shifts to somewhat in front of you. You can see this in your headlights on a rainy or snowy night.

Solar-system dynamicists have gotten rather good at predicting when a particular shower might display an extra burst of activity. Usually these bursts, typically lasting just a few hours, are from thin, denser"ribbons" of particles embedded in the larger stream — particles that were ejected by the parent comet only decades or centuries ago and have not had time to disperse much. And some meteoroid streams have a higher proportion of large particles than others, which create more fireballs.

The table and descriptions below list the year's best and most dependable annual displays. (There are many more: The International Astronomical Union now recognizes more than 100 well-defined meteor showers and hundreds of other "shower candidates" that remain unconfirmed. But most are so weak that it takes trained and very patient observers, or nowadays automated cameras, to detect the pattern.)

How to Watch Meteor Showers

Find a dark location with an open view overhead as far from urban light pollution as you can get, and where no local lights glare into your eyes. Find a way to block any lights you can't escape and the Moon, too, if it's up; you want your best night vision so you can see more meteors. Your night vision improves for at least your first 30 to 45 minutes in the dark.

Make yourself comfortable in a reclining chair, and wear more warm clothing than you imagine you'll need. When you're exposed to a wide expanse of clear sky, radiational cooling chills you to a surprising degree even in summer. Especially if you're out in the coldest hours of the late night, and if you aren't moving!

A sleeping bag provides warmth and mosquito protection. Put DEET repellent on your exposed parts if it might be buggy. Lie back, gaze into the darkest part of your sky (usually straight up), contemplate the stars, and be patient.

For more on watching, counting, and studying meteors, see Advanced Meteor Observing and other articles in the Meteor section of our website. To dive deeper, check out the abundant material at the International Meteor Organization.

Meteor Showers in 2024

The dates in the table below are for the predawn hours in North America closest to the predicted peak of Earth's passage through the meteoroid stream. Most showers are also active to some degree for a number of nights before and after the predicted peak date.

Important: The listed "zenithal hourly rate" is what a viewer would see under ideal conditions: a very dark sky free of moonlight or light pollution (stars of magnitude 6.5 detectable naked-eye), with full dark adaptation and the radiant high overhead. Rarely are we so blessed, so most likely you'll see lower rates than those listed.

| Major Meteor Showers in 2024 | ||||

| Shower | Radiant (and its rough direction) | Morning of maximum | Peak zenithal hourly rate | Parent comet or asteroid |

| Quadrantids | Boötes (NE) | Jan. 4 | 25-110 | 2003 EH1 |

| Lyrids* | Lyra (E) | April 22 | 10-20+ | Thatcher (1861 I) |

| Eta Aquariids | Aquarius (E) | May 5, 6 | 50 | 1P/Halley |

| Delta Aquariids | Aquarius (S) | July 25 - Aug. 5 | 15 | 96P/Machholz |

| Perseids | Perseus (NE) | Aug. 12 | 100 | 109P/Swift-Tuttle |

| Orionids* | Orion (SE) | Oct. 21, 22 | 20 | 1P/Halley |

| Taurids | Taurus (overhead) | Oct. - Nov. | 5-10 | 2P/Encke |

| Leonids* | Leo (E) | Nov. 18 | 10-20 | 55P/Tempel-Tuttle |

| Geminids* | Gemini (E) | Dec. 13, 14 | 120 | 3200 Phaethon |

| Ursids | Ursa Minor (N) | Dec. 22 | 10 | 8P/Tuttle |

Bold type indicates the best predicted showers this year.

* Strong moonlight will interfere.

January 4: The Quadrantids

Sky & Telescope diagram

In some years the "Quads" deliver at least 1 or 2 meteors visible per minute under excellent sky conditions — if everything aligns just right. In fact, the nominal zenithal hourly rate (the ZHR: seen by someone under a perfectly dark sky when the shower's radiant is overhead) is a very high 110 — in some years it's been 200!

But few observers ever see anything close to that many Quads, because the shower's peak lasts only about 6 hours. That brief period is likely to miss your vest meteor-watching hours depending on what side of the globe you live on. In 2024 the predicted timing is good for North America, especially the East: 9:00 UT (4 a.m. EST) on January 4th. But the light of the last-quarter Moon washes the morning sky.

The radiant is in northernmost Boötes, between the end of the Big Dipper's handle and the head of Draco. It's highest before dawn.

The parent of this shower is a small object designated 2003 EH1 for its discovery year (now it's also known as asteroid 196256). It loops around the Sun every 5½ years between the orbits of Earth and Jupiter. In 2004 meteor specialist Peter Jenniskens discovered that this body is responsible for the Quadrantids. It's not an active comet — more likely it's an "extinct comet" that no longer has any ice to evaporate.

April 22: The Lyrids

More than 3½ months pass until the next major annual shower. April’s Lyrids are usually weak; you might glimpse one every 5 minutes on average. But surprises occur; counts exceeded one a minute during a Lyrid outburst in 1982. The center of the stream is sometimes narrow and brief; its predicted peak this year (near 9h UT) is best for western North America. But the full Moon washes out the view.

May 5 and 6: The Eta Aquariids

This annual shower originates from none other than Halley's Comet, and its meteors come in fast: 66 km (41 miles) per second. This blazing speed often creates trains — something like incandescent smoke trails — that linger for several seconds after the meteors themselves have come and gone. However, the shower's radiant (in the Water Jar asterism of Aquarius) stays low before dawn as seen from mid-northern latitudes, so rates for us are low. For the Southern Hemisphere this is often the best shower of the year. This year there's no moonlight. The shower remains fairly active for a week or so around the peak dates.

Mid July – mid August: The Delta Aquariids

This long-lasting shower, more formally called the Southern Delta Aquariids, has a radiant below the celestial equator and thus, like the Eta Aquariids, is best seen from the Southern Hemisphere. The shower is at least slightly active all the way from mid-July to mid-August, but is most so for a week around the nominal maximum date of July 31st. For us northerners, its radiant well above the southern horizon for a couple of hours before midnight to a few hours after midnight. New Moon this year comes on August 3rd.

August 12: The Perseids

Even casual skywatchers know about the Perseid shower because it often delivers an average of a meteor per minute, under pleasant summer skies during vacation season when more people than usual are under unspoiled rural darkness.

Sky & Telescope / Dennis di Cicco

The first-quarter Moon sets before midnight on the nights of this year's predicted Perseid maximum, leaving the sky dark for the early-morning hours when the Perseid radiant is highest. Make your plans!

You'll catch some Perseids in the evening too, just not as many; the later you watch the better. On the other hand, the Perseid radiant (near the Double Cluster in Perseus just under Cassiopeia) clears the northeastern horizon by roughly 8 p.m. When the radiant is low, the few Perseids you see will be dramatically long, skimming almost horizontally far across the top of Earth's atmosphere.

Perseid activity builds up slowly earlier in August, then drops off more rapidly in the nights after the peak. The Perseids are bits of debris shed by Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which orbits the Sun every 130 years. Careful observers first realized that the Perseids are an annual event in the 1830s.

October 21 and 22: The Orionids

Here's another shower due to Halley's Comet; Earth makes two passages through Halley's meteoroid stream in our annual circle around the Sun. Like the Eta Aquariids, this shower lasts for several nights running. But this year, the light of the waning gibbous Moon will be a problem during the early-morning Orionid-watching hours. The radiant (in Orion's dim club, above Betelgeuse) is highest in the hour before the beginning of dawn.

When at their very best, such as 2006–09, the Orionids boasted peak rates of more than 50 meteors per hour. Since then the activity has dwindled to a fraction of that.

Mid-October – mid-November: The Southern Taurids

Late October – late November: The Northern Taurids

The broad, weak, combined Taurid display sputters along from early October through mid- to late November. It typically produces five or 10 meteors per hour around the poorly defined maximum, when the two branches of the shower overlap. Moreover, while both components include bits of debris shed by Comet 2P/Encke, a recent analysis shows that a host of other objects — near-Earth asteroids, collisional fragments, and dormant cometary nuclei — might be creating several overlapping streams of particles. Consequently, both Taurid components have broad maxima that aren’t easy to pin down.

What makes the Taurids potentially exciting is that they are known for a high proportion of bright fireballs — occasionally, an extremely bright one that makes the news.

The Taurids strike the atmosphere at a relatively slow 19 miles (30 km) per second. They are catching up with Earth from behind, which means that unlike the case with most showers, they're most numerous in the evening.

November 18: The Leonids

The Leonid shower's parent comet, 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, tends to leave narrow, concentrated streams of debris. These produced prodigious displays in the late 1990s, when the comet itself last swung through the inner solar system. Since then the shower's activity has greatly declined, usually offering just a slight trickle radiating from Leo’s Sickle in the hours before dawn. And this year, a bright waning gibbous Moon will wash out the already weak showing.

December 13 and 14: The Geminids

This shower in frigid nights is usually the year’s best and most reliable, with upward of 100 meteors per hour radiating from a spot near Castor in Gemini. The radiant is well up in the sky by 9 or 10 p.m. as seen from mid-northern latitudes and is highest overhead around 2 a.m. This year the nearly full Moon throws a damper on the party, but a few of the brightest meteors should shine through the moonlit sky.

We list two peak mornings for the Geminids this year because for North Americans, the shower's fairly brief maximum should fall between them. It's predicted for about 21h UT December 13th, which is 5 p.m. on that date Eastern Standard Time.

Geminid meteors come from 3200 Phaethon, an asteroid discovered as recently as 1983 that circles the Sun every 3.3 years. The particles are denser and stronger than typical shower meteors. Phaethon might be considered a "rock comet" that sheds bits when its rocky surface heats up to roughly 1,300°F (700°C) at perihelion, blazingly close to the Sun.

December 22: The Ursids

Although the Ursid shower delivers only a modest 10 meteors per hour even under the best conditions, it has the advantage of a radiant near the bowl of the Little Dipper in the north — so it's up all night for skywatchers at northern latitudes. Peak activity, which lasts just a few hours, is predicted for around 5h UT on December 22nd, meaning midnight EST on the night of December 21-22, well timed for North America. The last-quarter Moon that night rises around 11 or midnight.

PS: Did I mention that meteor observing requires patience? Kind of like the rest of amateur astronomy? In the Sunday newspaper comics after the 2022 Geminids, there appeared this Arlo and Janice strip.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.