The youngest planetary nebula ever found is already fading, shedding light on its star’s evolution.

It’s easy to believe that the constellations and other celestial wonders have always been around. But nebulae such as the Cat’s Eye and Ring nebulae are actually newcomers, astronomically speaking. It’s just that generations of humans come and go before changes become noticeable.

Well, not always. This is a story about an unusual planetary nebula, the Stingray, which we’ve watched rapidly fade over just 20 years. But that’s end of the story. Its beginning was just as sensational.

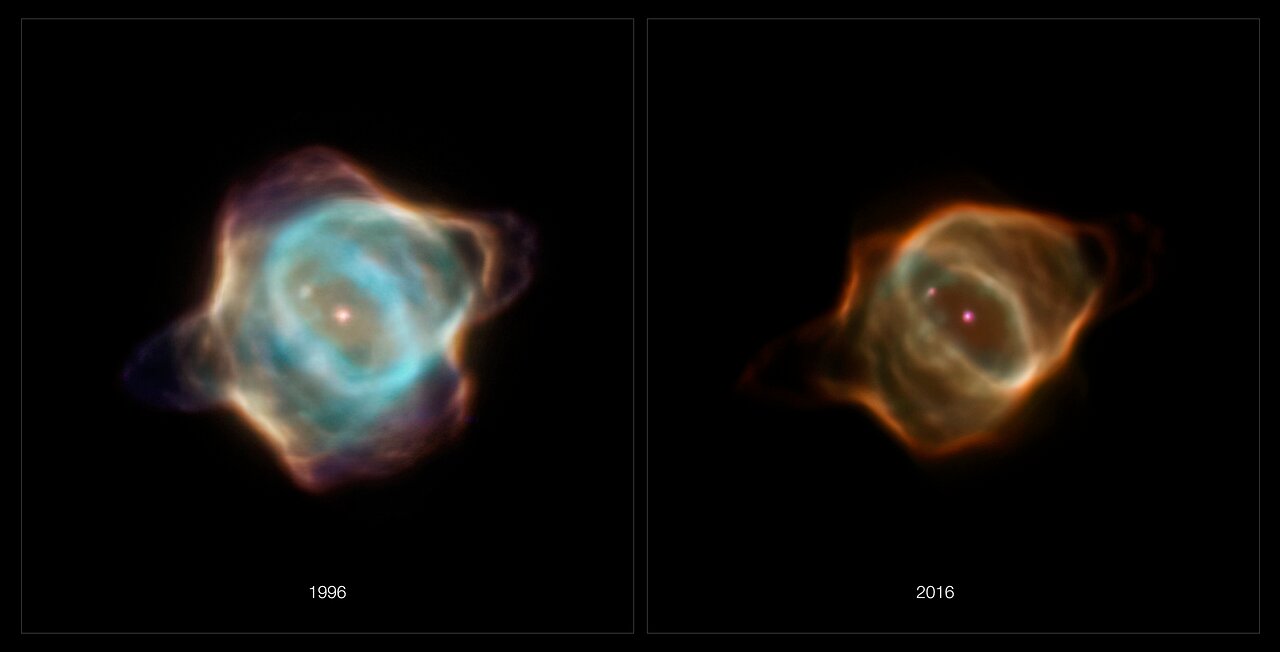

NASA / ESA / B. Balick (University of Washington) / M. Guerrero (Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía) / G. Ramos-Larios (Universidad de Guadalajara)

The Lives of Planetary Nebulae

Planetary nebulae are colorful and often dazzling objects that have nothing to do with planets. These clouds of gas are made by ordinary stars as their lives wane. Much like a car running out of gas, a low-mass star coughs and shudders as it becomes too cool to burn the last of its hydrogen. Its surface rattles and shakes out material that forms an expanding nebula. About 1,000 years later, the harsh ultraviolet light emitted by the shrinking star lights up the gas, much as electricity causes neon lights to fluoresce.

Planetary nebulae persist for a few thousand years as the dying star slowly but relentlessly radiates its last heat into space and cools off. Some of these nebulae have hovered in the sky since the years of the Neanderthals and Cro Magnons. But dinosaur astronomers never saw any of our familiar planetary nebulae, and all of the planetary nebulae that they might have identified are long gone.

The Hubble Space Telescope has observed about 100 of these objects, starting with the Cat’s Eye nebula in 1994. By comparing images spanning 20 years or more we can watch the nearest of these gently expand without changing their shapes or brightness.

But Stingray, a planetary nebula around the star SAO 244567, has its own ideas. People have periodically observed the star since the 1890s, but its planetary nebula seems to have appeared in the 1980s when we weren’t watching. Hubble was the first to capture its image in 1992. Matthew Bobrowsky, who used Hubble to discover the Stingray, called it the “youngest planetary nebula” in a 1998 research paper published in Nature. This makes it the only planetary nebula to have been caught shortly after it became luminous.

Now, for the first time, my colleagues and I — Martín Guerrero (Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, Spain) and Gerardo Ramos-Larios (University of Guadalajara, Mexico) — have found that the Stingray Nebula seems destined to vanish in the next few years: Start to finish in a mere two human generations! Indeed, the nebula was already rapidly fading when its first images were obtained by Borkowsky. By 2016, the blue-green light emitted by doubly ionized oxygen in the gas clouds was 900 times fainter than in 1990. Such rapid fading has never been observed in a planetary nebula. (Mysteriously, reddish light emitted by hydrogen has faded much less, by a factor between 2 and 10.)

A Born-again Star

Its central star, SAO 244567, ejected the gas that comprises the nebula about 1,000 years ago. In the early 1980s, observations showed that the star’s brightness rapidly and unexpectedly dropped as the star suddenly shrank. At the same time, the star’s surface heated up by a factor of three (to 100,000°F, or 60,000°K) in a decade or so. As the hot star began producing ultraviolet light, the ejected gas fluoresced, thereby explaining the nebula’s sudden appearance in the 1980s. Since then, the nebula has been fading as the shrunken star emits less ultraviolet light.

This begs the question, “What happened inside the star in the 1980s when the Stingray first appeared?” One possible answer comes from a group headed by Nicole Reindl (Potsdam Observatory, Germany). The researchers posit that the star underwent a sudden helium flash, in which some unburned helium in the core of the star unexpectedly reignited. The burst of new heat sent the core of the star several paces backward in its normal evolution.

This event disrupted the visible outer layers of the star, sending them into a highly unusual state. Now that the helium flash has ended, the German team predicts that the core of the star will resume the ordinary evolutionary path that it had been following before the helium flash. As the star’s outer layers resettle, they may begin to brighten within the next 50 years, and the fluorescence of the nebula may well resume. The revived nebula will be “born again.”

Unfortunately, Hubble — now 30 years old — is aging. Last refurbished by astronauts in 2009 with six new steering gyroscopes, the telescope only has three that remain operational and one of these is showing signs of major degradation. We have no means of mounting another refurbishment right now, so the telescope has a limited lifetime. We can only hope that Hubble lasts long enough to catch the nebular revival, assuming it actually happens. Fingers crossed!

6

6

Comments

Andrew James

December 3, 2020 at 5:37 pm

Bruce. Thank you very much for this article. I had read your paper on 4th September, and did comment on the Stingray nebula changes in a lecture "Recent Developments in Planetary Nebula Astronomy." This was just two weeks ago to my astronomical society. I purposely highlighted how dynamic these deep-sky objects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

December 6, 2020 at 4:29 pm

Basic calculation shows if we assume planetary nebula progenitors roughly exist for ten billion years, then its phases lasts 50,000 years. With 200 billion stars in the Milky Way, leaves on average one million planetaries. If its nebulosity is visible over 6,000 years, makes 120,000 possibly PNe. Seeing only 5% of the local Galaxy reduces to 6,000. Currently 3710 (2020) are known plus 200 PNe candidates awaiting. [Hence 2000 might still to be hiding. This also infers few are undergoing transformation like the Stingray nebula now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mike

December 6, 2020 at 12:42 pm

Thanks for this very interesting and informative article. Lucky for us primates that those dinosaur astronomers were preoccupied with planetary nebulae and weren't watching out for Earth-crossing asteroids.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

December 6, 2020 at 4:04 pm

Indigenous Australian culture goes back >50,000 years, which is the duration of a planetary nebula overall lifetime. What I still find most remarkable is the short transience of planetary nebulae (PNe) on astronomical timescales.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

December 6, 2020 at 3:58 pm

I've tried to post a useful comment here for several days and it keeps being rejected. The comment has no links nor anything that could even slightly be taken as offensive. The only thing accepted was the post above, with the last sentence merely truncated. Thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

December 6, 2020 at 4:30 pm

I rewrote the text. Probably thought a duplication. Thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.