Uranus and Neptune, the so-called ice giants, are the only major planets in our solar system that aren't easily visible to the unaided eye. Finder charts for them appear each year in Sky & Telescope.

If you've never seen Uranus or Neptune before, it's nice to know how they were discovered in the first place. Every time you set out to find a new celestial object, you are in some sense reliving the original discovery.

The Discovery of Uranus

In 1779, an obscure amateur astronomer named William Herschel decided to view all the bright stars in the sky at high magnification to see if they were double stars. Two years into this project, on March 13, 1781, he noticed a "star" in Taurus that looked quite different from all other 6th-magnitude stars when viewed at 227× in his homemade 6.2-inch reflecting telescope. When he observed it again four nights later, it had moved with respect to the background stars, proving that it was actually an object inside our solar system. At first, he assumed that it was a comet.

Wikimedia Commons / PD

When professional astronomers viewed Herschel's "comet," they saw only a garden-variety star. That's because — unknown to him or anyone else — Herschel's homemade reflector was far superior to most professional scopes. But it was easy to watch Herschel's object moving from one night to the next, and that allowed mathematicians to compute its orbit. It turned out to take a nearly circular path around the Sun, just like all the known planets, and very unlike the elongated orbits of comets. And the new object was much farther from the Sun than any solar-system body had ever been seen before. Considering how bright it appeared, it must be many times bigger than Earth.

Herschel had, in fact, stumbled upon the discovery Uranus — the first new planet discovered throughout all of human history and one of the now-known ice giants. Locating this ice giant was the most revolutionary discovery since Galileo spotted the moons of Jupiter 170 years earlier. Herschel became an instant celebrity and won a stipend from the King of England that allowed him to become a full-time astronomer.

The Discovery of Neptune

Once Herschel had overturned the millennia-old wisdom that there were exactly five planets besides Earth, astronomers started actively searching for new ones. And indeed, four new planets were discovered between 1801 and 1807, all orbiting between Mars and Jupiter. But these were tiny compared to Earth, let alone Uranus — too small to show as extended disks through most telescopes. Herschel, by then the grand old man of astronomy, called them asteroids because they look just like stars (Latin astra). Asteroids' rapid motion with respect to the "fixed" stars makes them great targets for backyard telescopes.

It wasn't until 1846 that another really large planet was found. And Neptune, as the new planet came to be called, was found in much the same way that you're going to find it. J. G. Galle and H. L. d'Arrest, staff astronomers at the Berlin Observatory, looked where the new planet was predicted to be, compared what they saw with a star chart, found an uncharted star, and then verified that it was in fact a planet.

But credit for the discovery goes not to the astronomers who first saw Neptune but to Urban Jean Joseph Le Verrier, who predicted where it would be found. It had been known for some time that Uranus didn't move exactly as it should, taking the gravitational attraction of the Sun and the known planets into account. Le Verrier analyzed the discrepancy, concluded that it must be due to the pull of a large planet well outside Uranus's orbit, and predicted the new planet's location with an error of just one degree. It was a stunning triumph for theoretical astronomy.

How to Observe Uranus

As the story of its discovery indicates, Uranus is easy to see once you've identified it with a finder chart, but it's not so easy to recognize as a planet. If you're willing to use our sky charts to identify the planet — taking it on faith that we're telling the truth — then you won't need any tools besides binoculars. In fact, you might be able to detect Uranus with just your unaided eyes if your sky is very dark.

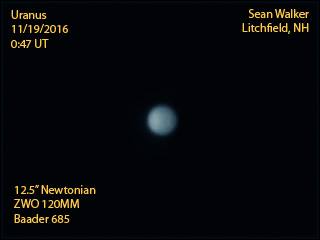

S&T: Sean Walker

But you'll need to examine the planet quite carefully with a telescope at 100× or higher to see that it's actually a tiny disk rather than a pinpoint of light like a star. That means that you need to pinpoint its location precisely. Being in the right general vicinity isn't good enough. It's easy to scan right over Uranus without noticing that it's anything but a regular star. Remember — many generations of highly skilled observers before Herschel did precisely that.

You may be able to recognize Uranus just by its hue, which most people find faintly blue or green. Contributing Editor Tony Flanders can see the color even with his 10×50 binoculars. Through a telescope, even at magnifications too low to see the planet's disk, you may notice that it shines with a steadier light than other similarly bright stars. And at 120× in a 70-mm telescope, Tony can quite clearly make out a tiny disk or dot — about the size of the period at the end of this sentence. Don't expect to see any features on the ice giant planet, though. Even giant professional telescopes can barely do that.

If you have a large telescope, at least 10 or 12 inches, you can the S&T javascript utility Moons of Uranus to predict their positions for your observing time.

How to Observe Neptune

Neptune and Uranus are near-twins in actual size, but Neptune is about 50% more distant, which makes it surprisingly much harder to find. But if you can find Uranus, you can find Neptune too. It just requires using the same techniques more carefully.

Neptune varies from magnitude 7.8 to 8.0, about two magnitudes fainter than Uranus. It's visible in steadily-supported binoculars, but only if you look quite carefully and the light pollution isn't too much. And while Uranus is frequently brighter than any other star visible in the same binocular or finderscope field, the sky is crowded full of stars as bright as Neptune. So you have to be careful when you match up your charts with what you see through the eyepiece.

Having said all that, it's worth remembering that even a very small telescope can easily show stars down to eighth or ninth magnitude. So Neptune is not faint by telescopic standards. In fact, it's bright enough to stimulate color vision through a telescope with 4 inches (100 mm) or more of aperture. Look for a hue quite similar to Uranus's, though perhaps a trace bluer.

Neptune's disk is visible at 200× through a 6-inch telescope on a night of steady seeing. But it may be quite hard to see the disk if conditions are bad or your telescope is improperly collimated. Tony's 70-mm refractor is a little too small to resolve Neptune properly, but when he examines the planet carefully at 120× it looks clearly different from a star of similar brightness. Neptune's light is distinctly steadier, and it appears more solid. Not exactly a disk, but a fat pinpoint.

If you have a large telescope, use the S&T javascript utility Triton Tracker to predict the position of Neptune's largest moon.

6

6

Comments

June 21, 2016 at 1:50 pm

I'm going to give it a shot at seeing Uranus and Neptune. I have 2 telescopes, one is a 70mm refractor, the other is a 130mm reflector. I'm learning to collimate it, so i can get the best views.I have bought some better eyepieces than the one's that came with these scopes. So I hope to see them sometime late this summer or early fall.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

JR

June 22, 2016 at 6:56 am

Good luck! I recommend starting with Uranus, which you can see even with small-ish binoculars (although it looks just like a star with small binos). I also recommend dark skies (because Pisces is dim), patient star-hopping, and making a sketch of all the field stars. Come back to the same field in a week or two, make another sketch, and you'll see how far Uranus has moved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dave Mitsky

September 30, 2021 at 11:01 pm

I observed Neptune most recently on September 27th using the Naylor Observatory's 17" f/15 classical Cassegrain at magnifications ranging from 170 to 432x. The conditions weren't the best and I wasn't able to see Triton. Neptune exhibited its characteristic bluish hue but at 2.3 arc seconds in angular size did not appear very large even at 432x.

https://www.astrohbg.org/

You must be logged in to post a comment.

StarsInMyAugen

October 29, 2021 at 5:21 pm

Please add back the wider-angle charts of Uranus and Neptune, as they appeared in two recent issues of S&T, to make it easier to locate the starfields.

Also, on the night of Nov. 2-3, Ceres passes just 7 arcminutes south of Aldebaran. From then through November 21, Ceres, moving retrograde, moves along the southern arm of the “V” formed by Aldebaran and stars of the Hyades star cluster. A finder chart for Ceres appeared in a recent issue of S&T. I am hoping that chart will be made available online in time for the conjunction of Ceres with Aldebaran. Two other events worthy of mention are:

(1) Ceres passes north of the naked-eye double star Theta-1 and Theta-2 Tauri on November 12. These stars are 5.5’ (arcminutes) apart, Theta-1 being the northern and fainter member at mag. 3.8. (Theta-2 is of mag. 3.4.) The 5.0-mag. star 75 Tauri is 24' north of Theta-1, and on Nov. 12, Ceres, of mag. 7.3, passes within 9' north of 75 Tauri. The conjunction takes place in the afternoon in North America, with Ceres going west by 12' per day.

(2) Ceres passes 1°.0 north of 3.7-mag. Gamma Tauri, the point of the "V" of the Hyades cluster, on the evening of Nov. 21, for North America. The 6.9-mag. star 55 Tauri is 0.9° north of Gamma Tauri, and Ceres, then of mag. 7.1 and moving west by 14' per day, passes nearly 7' north of 55 Tauri. Only five nights later, on the night of Nov. 26 in North America, Ceres reaches opposition at mag. 7.0.

The stars 55 and 75 Tauri are labeled on the Sky and Telescope Pocket Sky Atlas. Readers aware of these stars will avoid mistaking either one for Ceres on the nights of Nov. 12 and 21, and instead use each star to help locate the asteroid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Brian

October 26, 2022 at 8:57 am

Best observation uranus with 6 inch refractor. I saw 5 or 6 moons down to the 16th mag one. This was from a bortle 4 area with 4/5 plus seeing and only 10 min out of a 3 hour session. I has rested my eyes for 15 min and went back to the ep

https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-HPXa9uGVcQA/XfOpy046DMI/AAAAAAAAGNs/Wghwsaxb4Rwqc7BQ9UYUXYYpj2WxwKDoQCLcBGAsYHQ/s1600/20191213_082656.jpg

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Brian

October 26, 2022 at 9:02 am

This is the correct image

https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-HPXa9uGVcQA/XfOpy046DMI/AAAAAAAAGNs/Wghwsaxb4Rwqc7BQ9UYUXYYpj2WxwKDoQCLcBGAsYHQ/s1600/20191213_082656.jpg

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.