It doesn’t take much to create a spectacle when it comes to astronomical observation. Just a pinch or two of dust.

Phil Hart

"I would rather be ashes than dust! I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet." – Jack London

Nature fashions beauty with dust. There are few better ways to witness this than watching a meteor shower, when the Earth slams into the debris left behind in a comet's or asteroid's orbital path. Sand-grain to pea-size dross blitzes the atmosphere at tens of thousands of miles per hour. Particles glow hot from the impact, heating and compressing the air to create javelins of ionized light. Every meteor represents an interplanetary grain's transition from outer space to earthly space. After the show is over, sooty leftovers remain aloft and fulfill a second role as nuclei for the formation of summertime's filigree noctilucent clouds.

Bob King

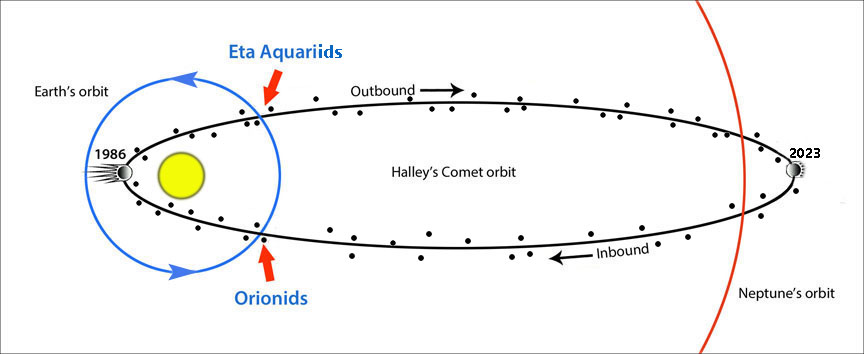

You can watch the tale unfold again on Friday morning, October 21st, when Earth barrels into the path of Halley's Comet and gets pelted with dusty bits that once fattened its coma and tail. Now diffused along the comet's orbit, we encounter the stream twice a year: First in May during the Eta Aquariid shower, when we cross Comet 1P/Halley's outbound debris trail, and a second time in October, when we encounter the inbound stream as the Orionid shower.

<iframe src="https://www.meteorshowers.org/view/iau-8" width="500" height="500" frameBorder="0"></iframe>Comin' atcha!

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

Whenever we move through a cloud of small objects, whether it be meteoroids in space or driving in a car through a snowstorm, meteor trails and snowflakes appear to converge in the distance at a vanishing point — a useful optical illusion that aids in depth perception. During our October Halley encounter, meteors stream from a point in Orion's upraised club about 11° northeast of the bright, red supergiant star Betelgeuse at the rate of 15–20 per hour. This year maximum activity is expected between 1 a.m. local time and the start of dawn on October 21st.

What sets the shower apart from many is the swift speed of the incoming meteoroids. Each fragment strikes the atmosphere at 238,000 kilometers per hour (148,000 mph) between 80 and 120 kilometers (50–75 miles) high. Of the major meteor showers, only November's Leonids are swifter. While you can always identify an Orionid by tracing its path back to northern Orion, the bullet-like rapidity of the flash will help confirm your observation.

Dressing for success

As with any shower, warmth and comfort are essential. Dress like you're going out ice fishing in the middle of winter and relax on a fold-out reclining chair tipped back about halfway. Give it an hour, maybe an hour-and-a-half, to let the dust work its magic. When Orion's near the meridian I usually face southeast or southwest to catch a mix of short-trailed meteors near the radiant and longer ones that flash farther away. The waning lunar crescent rises in Leo around 3 a.m. local time, so the Moon won't pose a problem this year.

Be aware that the North and South Taurid meteor streams are also in play from late October through November. Meteor experts expect heightened activity from both this year. Although rates are typically just a few per hour, these showers tend to produce bright, slow fireballs. Both radiants are located in western Taurus near the Pleiades cluster.

The Orionids are active from late September until the third week of November, so if you're skunked by bad weather on October 21st, the surrounding few nights provide good opportunities for a second chance.

Capture speeding photons

Bob King

To photograph the shower from a dark sky, use a wide-angle lens (12–35 mm) at its widest opening (f/2 to f/4), an ISO of 1600 or 3200 and a time exposure of 30-seconds. Frame a bit of landscape to provide perspective. Intervalometers make meteor photography easy by automatically tripping the shutter at a set time interval while you kick back and enjoy. They're built into newer cameras, but you can acquire one on Amazon or another outlet. To prevent frost or dew from forming on your optics, rubber-band two chemical handwarmers around the top and bottom of your lens. Under a light-polluted sky, dial back the ISO to 800 or 1600.

Dust in the solar wind

Bob King

We're not done with dust quite yet. From about October 23rd through November 6th, the early dawn sky is untouched by moonlight, making it ideal for observing the zodiacal light. This tall cone of dusty radiance rises in Virgo and tapers upward with a rightward slant, fading along its length. Under excellent skies its fuzzy fingertip tickles Gemini and merges with the Milky Way — a distance of nearly 100°!

Stellarium

The softly luminous glow seems almost atmospheric, but we're looking at interplanetary dust that resides primarily between Earth to just beyond the orbit of Mars. Long thought to originate from debris sloughed by comets or released during asteroid smash-ups, recent evidence indicates that Martian dust storms also may be an important source. The dust forms a pancake-like disk centered on the plane of the solar system, so it's no surprise it follows straight up the ecliptic. Backscattered sunlight illuminates the particles the same way dust kicked up by a car on a dirt road glows brilliantly when backlit by the Sun.

While the zodiacal light is always present in the sky, it's often rendered invisible by atmospheric extinction or haze near the horizon. However, at mid-northern latitudes from late September through mid-November the ecliptic meets the eastern horizon at a steep angle in the predawn sky, tilting the otherwise faint glow into good view. The same circumstances prevail on spring evenings.

Bob King

The bottom half of the zodiacal wedge resembles the brightness of the summer Milky Way but with a smoother texture. The top half is a good match for the fainter regions of the winter Milky Way. A dark eastern sky is a must to ensure you don't confuse heavenly light with the profane domes of city-light pollution. Look for a giant, towering glow tilted on its right side. While subtle there's nothing small about the zodiacal light.

You can see a portion of it poking above up in the east as early as 2.5–3 hours before sunrise, but just before the end of astronomical twilight is best. That would be about 90 to 105 minutes before sunup. Click here for your local sunrise time, then head out before dawn to commune with the dust.

12

12

Comments

Jabberwocky

October 19, 2022 at 1:39 pm

I think I may have seen something like the zodiacal light--I was just finishing up my stargazing and I saw over my mountain two or three faint beams of light. They were very wide, and certainly weren't anything man made, as they weren't bright enough. They also stayed in the same spot all the time. (Then again, I was only looking for a few minutes.) The moon rose about ten minutes later, which makes me wonder whether they were just beams of light from it. I've seen the almost the same thing in the evening when the sun comes through the clouds and you can see the beams.

What confuses me is that it wasn't even 12:00am, definitely nowhere near sunrise.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

October 19, 2022 at 11:37 pm

Hi Jabberwocky,

Thank you for sharing your observations. It's hard to say if the first instance you mentioned was the zodiacal light or moonlight. If I knew the date and time of your observation I could tell you. Regarding the sunbeams, that's a different phenomenon called crepuscular rays. It's strictly atmospheric and caused by sunlight (or moonlight) shining through gaps in clouds.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jabberwocky

October 21, 2022 at 9:06 am

It was around 11:40pm when I saw it, October 17.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

October 22, 2022 at 10:52 pm

Jabberwocky,

That would definitely be moonlight. The zodiacal light this time of year is only visible about one hour to 90 minutes before dawn.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 21, 2022 at 12:06 am

If the Moon was rising before midnight, she was in her waning gibbous phase. In an otherwise dark sky the glow of a gibbous or full Moon is visible on the horizon before the Moon rises, and after she sets. If the Moon was behind clouds or mountains, you might have been seeing moonbeams, like the sunbeams you describe seeing at another time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jabberwocky

October 21, 2022 at 9:04 am

Moonbeams, huh? Sounds correct. It was behind a mountain, but it was a very clear night, so maybe that's what it was. Thanks!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 21, 2022 at 12:08 am

That is a gorgeous photo of the zodiacal light reaching up through Leo and touching the beehive cluster.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

October 22, 2022 at 10:53 pm

Thank you, Anthony 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

October 21, 2022 at 6:47 am

Bob King et al. I did get out briefly last night and this morning for a few Orionids. Posted a note here, https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/observing-news/this-weeks-sky-at-a-glance-october-21-29-3/

Near 0625 EDT, the ISS passed by for a visit 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

October 22, 2022 at 10:53 pm

Good for you, Rod! We were cloudy in northern Minnesota.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chris-Schur

October 22, 2022 at 5:37 pm

Nice article Bob! Especially the notes on the Zodiacal light. Here in Arizona this time of year can be seen a huge "X" in the sky formed by the zodiacal band crossing the winter Milkyway and continuing across the entire sky all the way to the opposite horizon. And then theres that pesky bright spot that shows up opposite of the Sun - the Gegenschein. Have to be careful when you are out imaging not to shoot a deep sky object when in the middle of that...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

October 22, 2022 at 10:55 pm

Hi Chris,

Thank you. You have SUPERB skies then. I've seen the X but not from Minnesota. Spotted it and some pretty outrageous gegenschein from the Oklahoma Panhandle last March under spectacularly dark skies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.