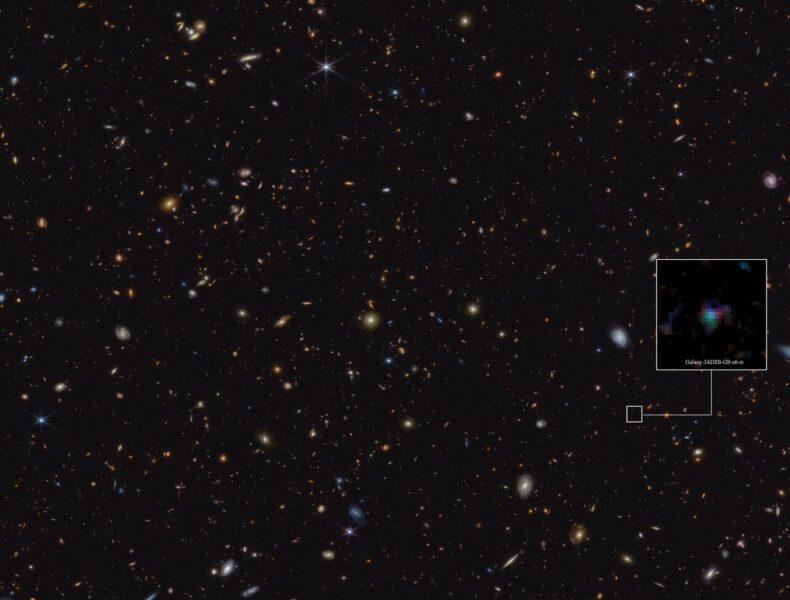

NASA / ESA / CSA / Webb / B. Robertson (UC Santa Cruz) / B. Johnson (Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian) / S. Tacchella (University of Cambridge, M. Rieke (Univ. of Arizona), D. Eisenstein (Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian) / A. Pagan (STScI)

The primary mission of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is to find the first galaxies. We’ve seen very little of the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang, but scientists have a lot of theories about how those first generations of stars lived and died.

Now, using JWST, an international team led by Joris Witstok (University of Cambridge, UK) has found a mysterious amount of dust in a number of distant galaxies from this early epoch. The results of their study, published in Nature, could pose some problems for some stellar evolution and dust formation theories.

Cosmic dust suffuses the universe. The smoke-like particles form in and around stars, and their composition varies by the type of star and the means of production. Some stardust is puffed out gently during a star’s lifetime, while some is created in violent explosions. Witstok’s team used JWST to look at 253 distant galaxies, which previous observations from the Hubble Space Telescope had already dated to the first billion years after the Big Bang.

The JWST spectra revealed something strange in the dust of 10 of these galaxies: a familiar spectral feature around 217.5 nanometers, colloquially called the “UV bump.” “It’s known to observers of the Milky Way and other nearby galaxies for its association with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs),” Witstok says. These are complex molecules containing two or more carbon-based rings. Astronomers think they form in the winds of dying stars known as asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars.

But Witstok’s team was not expecting to see evidence of PAHs in the early universe, because stars take longer than 1 billion years to evolve into the AGB phase. So where is all the carbon dust coming from?

“Something is making this dust very quickly,” Witstok says. In the study, he suggests that the dust might be formed in gas ejected by supernovae, or in the strong winds from rare, massive Wolf-Rayet stars.

Tayyaba Zafar (Macquarie University, Australia), who was not involved in this study, believes that this detection is exciting because it helps to constrain our dust production models and challenges star formation scenarios for the early Universe.

“This is going to open up a whole new debate in this field,” she says. “People will be rethinking which type of stars can produce sufficient dust to match these observations.”

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.