Astronomers are trying to understand why a giant star “blinked,” fading almost completely before brightening again over the course of about 200 days.

A red giant star nearly disappeared from the sky for about 200 days in 2012. At its minimum that April, only 3% of its light was arriving at Earth. Then it slowly brightened again until by the end of that year it was back to its normal giant-star self.

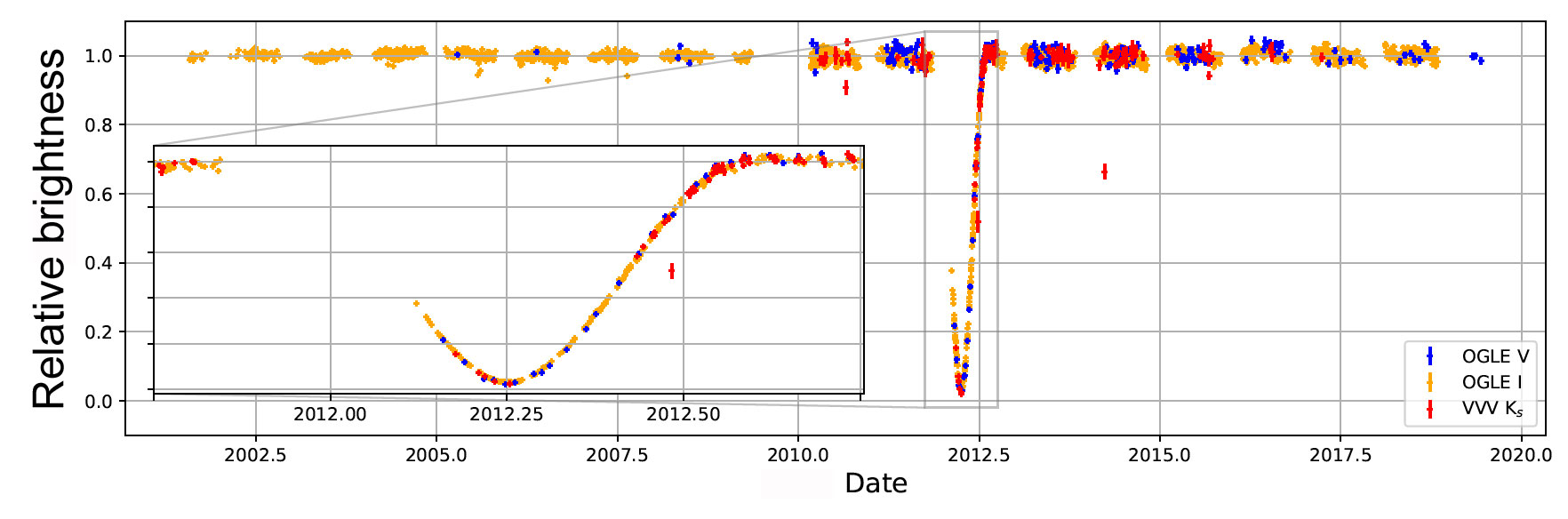

The event, whatever it was, was unique for this object. The star’s huge, smooth dip in brightness only happened once over the course of the 17 years that two surveys, the VISTA Variables in the Via-Lactea (VVV) and Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE), have been monitoring that portion of the sky.

Leigh Smith (University of Cambridge, UK) and colleagues will report the “blinking” star in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint available here). They suggest that a disk around a companion briefly covered the star, and may do so again one day.

L. Smith et al. / Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2021

“What Is This?”

For years, the VISTA telescope at the La Paranal Observatory in Chile has been systematically covering a region of the sky along the center of the Milky Way and along part of the galactic plane as part of the VVV survey. It monitors fields dense with stars, recording their brightness over and over again. Some stars stay steady, while others pulse in known and regular ways. But sometimes one of them captures the attention of astronomers, who flag it as a “what is this?” star (WIT for short).

The eighth one on this list, cataloged as VVV-WIT-08, is a red giant star that suddenly began fading around the beginning of 2012. While there’s a gap in observations when the star wasn’t visible, which makes it hard to tell exactly when the fade started, the measurements that were recorded show a smooth dimming and recovery. This behavior is in contrast to the square-shape dips that occur when smaller bodies, such as exoplanets, cross the face of their host stars.

After ruling out the idea that the star itself might somehow be fluctuating in brightness, Smith and his colleagues estimate that whatever is blocking the star’s light, it must be big — with a radius of at least a quarter of the distance between Earth and the Sun (0.25 astronomical units), and possibly even bigger. What’s more, it seems not to be spherical, instead having more of an elliptical or egg shape. In other words, whatever it is, it’s definitely not a planet!

Smith’s team instead suggests that the star could have a companion, whether a planet or another star, that is itself surrounded by a disk. Such a disk could be both large enough and of the right shape to block the giant star’s light.

However, it’s still unclear what the disk would be exactly. Disks of dust and gas surround young stars still in the process of forming, but a dusty disk would block more blue light than red, and the astronomers didn’t see that pattern in this case. The same goes for dusty disks around main-sequence stars. A disk around a white dwarf would be too small, and there’s no X-ray signature of the types of disks around neutron stars or black holes.

One possibility is that a planet in close orbit around the star stripped away some of its gas, surrounding itself in a gaseous cocoon. But even this doesn’t explain all the observations. As the researchers conclude, “Despite intensive efforts, it is clear that we have room left for further work on this intriguing object!”

Blinking Giants Abound

Meanwhile, it’s possible that WIT-08 might be a member of a small but expanding group of stars with disk-enshrouded companions. The group consists of several other cases (perhaps including the 10th and 11th objects on the WIT list) in which stars dip deeply in brightness, some more than once.

The most notable of these is Epsilon Aurigae, target of a famous observing campaign in 2009. Using interferometry, astronomers actually managed to image the disk as it crossed the face of the star back then.

While such detailed observations won’t be possible for the much more distant WIT-08, they could nevertheless tell researchers what to look for around the blinking giant and others like it.

4

4

Comments

Andrew James

June 21, 2021 at 8:34 pm

"The event, whatever it was, was unique."

Not quite true. Transient stellar phenomena has always been a fascination to me. Red Sirius or Algol is a early example, but there have been others. The origin of many of these claims were after the changes in brightness of Eta Carina between 1822 to 1845, which peaked to rival even Sirius itself. Rev. T. Webb lists in Appendix II pg.275 in the Dover (1962) speculation that Canopus once appeared brighter that Sirius or Epsilon Crucis had possibly dimmed to 6th magnitude around 1860. While some are clearly fiction, some are real, like some T Tauri stars or the R CrB variables. Transient events via exoplanets transiting stars show the reality of these ideas. We also tend to think that stars can only brighten like novae, whereas stars actually dimming over years or decades seems either very unlikely to impossible. This story possibly indicates we should perhaps revise our expectations.

Note: Reading Fred Hoyle's "The Black Cloud" (1957) novel conjures up how dark nebulae can sometime dim the background stars. A real example is McNeil's Nebula showing quick changes as a feasible scenario.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica YoungPost Author

June 22, 2021 at 9:53 am

Apologies, this should have read "was unique for this object" and I have edited to clarify. This star has not undergone any similar dipping events.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew James

June 22, 2021 at 6:35 pm

Sorry. No need for apologies here because I didn't read it that way. You already qualified it in saying; "...they could nevertheless tell researchers what to look for around the blinking giant and others like it." My own comment just extended that point. Such events are very rare but their behaviours are very broad, making them all unique in their own way..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica YoungPost Author

June 23, 2021 at 11:07 am

Ahh, got it. It's interesting to note, as you said, that brightenings have been recorded for centuries or even millenia, but dimmings have been occurring that whole time, too, if less remarked upon by astronomers until recently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.