FRIDAY, MARCH 10

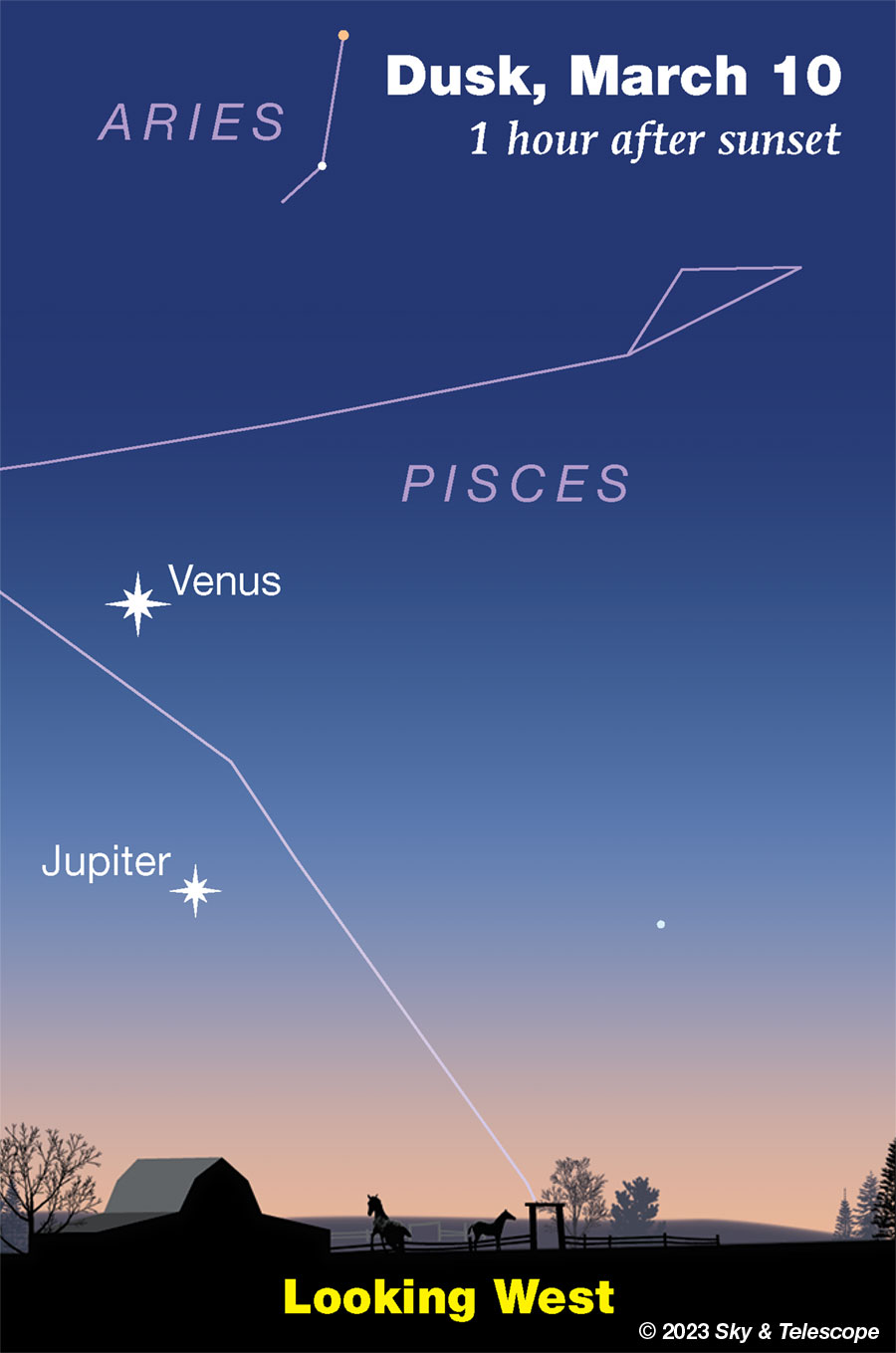

■ Venus and Jupiter continue to separate in the western evening twilight, as Jupiter sinks lower and Venus moves a little higher. We now see them 9° from each other, as shown below. The gap between them continues widening by about 1° per day.

Although they look like a pair, Jupiter is currently 4.5 times farther away.

SATURDAY, MARCH 11

■ Bright Sirius now stands due south on the meridian just as twilight fades into night. Sirius is the bottom star of the equilateral Winter Triangle; the others are orange Betelgeuse to Sirius's upper right (Orion's shoulder) and Procyon to Sirius's upper left. At this time of year, the Winter Triangle balances on Sirius soon after dark. The top of the triangle is perfectly level shortly thereafter.

■ Daylight-saving time begins at 2 a.m. tonight for most of North America. Clocks spring ahead an hour.

SUNDAY, MARCH 12

■ More about Sirius and Canis Major. In a good dark sky, the Big Dog's stick figure is fairly plain to see with the naked eye. The dog is in profile prancing to the right on his hind legs, with Sirius as the shiny dog tag on his chest. The stars of his triangular, pointy-nosed head are dim (4th magnitude).

For most of us, only his five brightest stars show through our light-polluted skies. These form the unmistakable Meat Cleaver. Sirius and Murzim (to its right) are the wide top end of the Cleaver, with Sirius sparkling on its top back corner. Down to Sirius's lower left is the Cleaver's other end including its short handle, formed by the triangle of Adhara, Wezen, and Aludra. The Cleaver is chopping toward the lower right. Its stubby handle is Canis Major's tail.

MONDAY, MARCH 13

■ This is a fine week to look for the zodiacal light if you live in the mid-northern latitudes, now that the evening sky is moonless and the ecliptic is tilting high upward from the western horizon at nightfall. From a clear, clean, dark site, look west at the very end of twilight for a vague but huge, tall pyramid of pearly light. It's tilted to the left, aligned along the constellations of the zodiac.

What you're seeing is sunlit interplanetary dust orbiting the Sun near the ecliptic plane.

■ After dark, Capella shines brightly high in the northwest. Between it and Polaris (43° to Capella's lower right due north) is a very dull region of sky — in fact blank for those of us with significant light pollution. This is the enormous celestial terrain of Camelopardalis, the Giraffe. Even if you can't see any of its dim, rather indecipherable star pattern, now you know the whereabouts of another constellation.

TUESDAY, MARCH 14

■ Last-quarter Moon (exactly last-quarter at 10:08 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time).

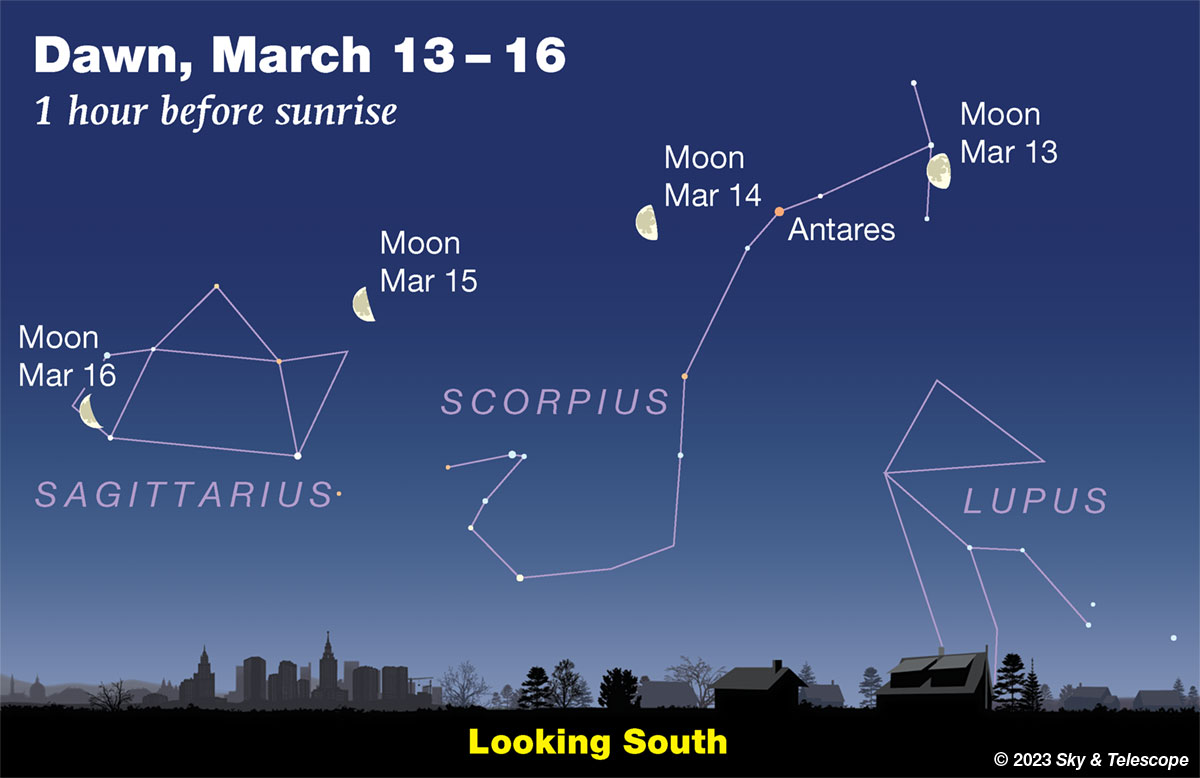

The Moon doesn't rise tonight until around 3 a.m. daylight-saving time on the 15th. It comes into view to the lower left of Antares and the head of Scorpius. Before dawn on the 15th, spot the Sagittarius Teapot sitting low and level closer to the Moon's own lower left; see above. The Teapot is about the size of your fist at arm's length.

WEDNESDAY, MARCH 15

■ It's just about the turn of spring. So when the stars come out, the Big Dipper is as high in the northeast as Cassiopeia has descended to in the northwest. Midway between them, as always, is Polaris.

■ Follow the curve of the Big Dipper's handle down and around, by a little more than a Dipper-length, to find bright Arcturus, the Spring Star. Or the place where it's about to rise! Arcturus comes up around the end of twilight depending on your location.

THURSDAY, MARCH 16

■ Pollux and Castor in Gemini pass nearly overhead around 9 p.m. daylight-saving time this week if you live in the world's mid-northern latitudes. They go smack overhead as seen from near latitude 30° north: Austin, Houston and the US Gulf Coast, northernmost Africa, Tibet, and Shanghai.

■ Gemini's feet wade in the Milky Way. The trailing foot of the Castor stick figure carries the big, showy open star cluster M35 just above it. The cluster, a favorite of deep-sky observers, is a dim, diffuse glow in binoculars and a rich spangle of faint stars in a telescope. Much farther, and thus much smaller and dimmer, is the open cluster NGC 2158, just a little way to M35's southwest.

But what about the other sights around here? Such as the Quad asterism, and just off the end of Castor's foot, the Toes? Lots of telescopic double stars also await, including the relatively bright pair ΟΣ 134 in M35 itself. See Ken Hewitt-White's "Best Foot Forward" guide in the March Sky & Telescope, page 54.

FRIDAY, MARCH 17

■ Spring arrives very soon (the equinox is on the 20th), so Orion stands upright high in the south-southwest as the stars come out. He's about to start his long spring tilt and departure down toward the west — as the hours pass in the evening, and as the weeks pass with the advancing season.

SATURDAY, MARCH 18

■ On the traditional divide between the "winter" and "spring" sky is the dim constellation Cancer, now very high toward the south. It's between Gemini to its west and Leo to its east.

Cancer holds something unique: the Beehive Star Cluster, M44, in its middle. The Beehive shows dimly to the naked eye if you have little or no light pollution. With binoculars it's easy even under mediocre conditions. Look for it a little less than halfway from Pollux in Gemini to Regulus in Leo. And see Fred Schaaf's "Sighting the Beehive" in the March Sky & Telescope, page 45.

SUNDAY, MARCH 19

■ The "twin" heads of the Gemini figures are fraternal twins at best. Pollux is visibly brighter than Castor and pale orange. And as for their physical nature, they're not even the same species.

Pollux is a single orange giant. Castor is a binary pair of two smaller, hotter, white main-sequence stars, a fine double in amateur telescopes. If Pollux were a basketball, white Castor A and B would be a brilliant tennis ball and baseball about a half mile apart.

Moreover, each Castor star is closely orbited by an unseen red dwarf — dim marbles in our scale model, only a foot or so from the tennis ball and the baseball.

And a very distant tight pair of red dwarfs, Castor C, is visible in amateur scopes as a single, 10th-magnitude speck 70 arcseconds south-southeast of the main pair. In our scale model, they would be a pair of marbles only about 3 inches apart at least 10 miles from Castor A and B.

Double stars come in a vast range of true separations — from nearly a light-year apart down to actually touching.

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury is hidden deep in the glow of sunrise.

Venus and Jupiter shine in the west at dusk. Venus is the brightest at magnitude –3.9. Jupiter, at magnitude –2.1, is one fifth as bright. And as Jupiter gets lower, it's increasingly dimmed by atmospheric effects: atmospheric extinction, and apparent "dimming" by being seen on a brighter sky background.

The two planets get farther apart every day. On Friday March 10th they's separated by 9° as shown at the top of this page. By the 17th they widen to 15° apart.

Telescopically, Venus is a shimmering little gibbous ball 13 arcseconds in diameter and 83% sunlit. Jupiter is 34 or 33 arcseconds wide, about as small as we ever see it; Jupiter is nearly on the other side of the solar system from us now. Moreover, Jupiter is getting very blurry in a telescope as it sinks to an ever-lower altitude.

Mars is in eastern Taurus, heading east against the stars toward Gemini. Look for it high in the southwestern sky in early evening, lower in the west later.

Mars continues to fade, from magnitude +0.5 to +0.7 this week. It's pretty similar to Mars-colored Aldebaran (+0.9) some 17° below it and Mars-colored Betelgeuse (currently +0.4) roughly the same distance to Mars's lower left. They form a big, temporary Orange Triangle.

Mars passes between the horntip stars of Taurus on March 11th, shining closer to Beta Tauri (on its right) than to dimmer Zeta Tauri (on Mars's left). Watch the planet creep away from the line between the two stars thereafter.

In a telescope Mars is now only 7 arcseconds wide. That's too small to show visual details in telescopes on most nights, aside from its gibbous shape (90% sunlit; see below).

Saturn is still hidden low in the sunrise.

Uranus, magnitude 5.8 in Aries, is in the west right after dark, above Venus. See the Uranus finder charts in the November Sky & Telescope, page 49.

Neptune is in conjunction behind the Sun.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is UT minus 4 hours. (UT is also called UTC, GMT or Z time.)

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows all stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. The next up, once you know your way around, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And be sure to read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham's Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer's Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don't think, and not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. And as Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty's monthly

podcast tour of the heavens above. It's free.

"The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It's not that there's something new in our way of thinking, it's that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before."

— Carl Sagan, 1996

"Facts are stubborn things."

— John Adams, 1770

4

4

Comments

misha17

March 11, 2023 at 12:16 am

Point objects like stars appear to instantly appear above, or disappear below.

Neglecting the fact that the atmosphere bends light so that a star is visible even though it lies slightly below the horizon*, a star lying on the Celestial Equator would have star-rise and star-set exactly 12 hours apart. If the Sun was a point object too, Sunrise and Sunset would be exactly 12 hours apart at the Equinoces.

However, the Sun's apparent disk is 1/4 degree in radius, so it takes a minute between the instant that the first bit (at sunrise) or last bit (at sunset) of the disk is at the horizon, and the instant that the center "point" of the Sun is on the horizon.

For this reason (* and also because of atmospheric bending), although the Sun's center is above the horizon for 12 hours at the Spring Equinox, the time between Sunrise and Sunset is already slightly longer than 12 hours on that day. The day when Sunrise and Sunset occur 12 hours apart occurs a few days earlier, for Los Angeles it falls around March 17th

You must be logged in to post a comment.

mary beth

March 13, 2023 at 10:56 am

Interesting, thank you.

I got on my Sun Surveyor App (highly recommend) and my date is March 16. The sun rises and sets at 7:29. I need to check the autumn date as well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

March 15, 2023 at 7:39 am

I may do some stargazing tonight. Winds howling yesterday and this morning 30-55 mph and woodburning stove lit up 🙂 Perhaps New Jersey Eclipse Fan got some snow 🙂 Tonight looks much better for some telescope time 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

mary beth

March 15, 2023 at 2:43 pm

Wow! Sounds brutal! Reminds me of this old adage:

“When the cat lies in the Sun in February,

she will creep behind the stove in March.”

Hopefully you’ll have something fun to tell us tomorrow! Beautiful weather here, but will be getting a cold front tomorrow night.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.