Tour 15 of the sky’s brightest stars all in one night on this New Year’s Eve! This interactive Worldwide Telescope video will show you the way.

Every year around the winter solstice, all 15 of the northern night sky’s brightest stars – those first-magnitude and brighter – are above the horizon and visible sometime between sunset and sunrise. Get the New Year off to a good start by coming along with Scott Levine and the Worldwide Telescope on our interactive video tour!

Note: This video is interactive! Besides the usual video controls, you can also use this as a window on the night sky. To start exploring, first pause the video, then click and drag the view to other parts of the sky, or zoom in and out of your current view using your mouse (or two fingers if on a mobile device).

Video Transcript:

Hi, I’m Scott Levine. Thanks for taking some time to stop by Sky & Telescope’s tour of some of the sky’s brightest stars.

One of my favorite holiday traditions is taking a break from the rush to spend time with some friends on New Year’s Eve: the 15 stars visible from mid-northern latitudes, figure around 40 degrees north, that are first magnitude or brighter. They’re all above the horizon at some point between sunset December 31st and sunrise January 1st, New Year’s Morning. It’s fun to make the most of the long nights around the winter solstice for a tour of the skies’ brightest lights. Ready? Let’s get to it.

Stellarium

The last time most of us thought about the Summer Triangle, it was popping into the sky over the eastern horizon after a long, slow, summer sunset. In August, the constellations Cygnus, the Swan, and Aquila, the Eagle soared high overhead, lighting up those sweltering skies with Lyra, the Lyre, between them. But — believe it or not — the Summer Triangle’s stars are still in winter evening skies too. Let’s start our tour with them, looking toward the western horizon after sunset just as the skies start to dim. As the New Year’s festivities start, we’ll see the Swan and Eagle gliding into the dusk, chasing after the Sun.

Altair and Vega are among the closest stars to us, only about 17 and 25 light-years away, respectively. But Deneb, which forms the Swan’s tail, is one of the most distant stars we can see with the unaided eye. It’s an old, giant star whose exact distance is a little tough to pin down. Estimates suggest that the light we see now has been traveling toward us for about 2,000 years. It’s dimmer than the other two stars, but even from so far, it’s still very bright. If it’s so bright from its current distance, imagine what it must be like much closer to it.

These stars are all wonderful in the summer, but there’s something special about seeing them in the dusky early evening sky in the winter, and letting your mind wander back to hot dogs, baseball games, and trips to the beach.

They’re not visible long, though. Altair sets around 7:30, with Vega and Deneb not too far behind. If you’re fortunate enough to live under good, dark skies, away from light pollution, you might also be able to make out the Milky Way’s glow cutting right through the center of the Triangle and then up overhead.

NASA / ESA

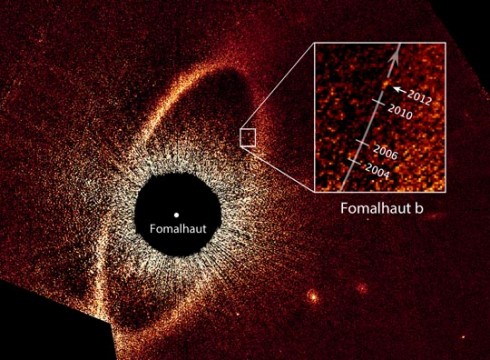

While we’re still looking westward, after we’ve found those first three stars, it’s a quick hop to the fourth. The southernmost first-magnitude star visible in the north is Fomalhaut, whose name comes from Arabic and means “the mouth of the whale.” Piscis Austrinus, the Southern Fish, not to be confused with Pisces the directionally agnostic fish, is a dim and sparse constellation that can be tough to see because our view of it puts it low in the southern sky. Fomalhaut never rises more than about 20 degrees above the horizon from mid-northern latitudes. The farther north you are, the closer to the horizon it is.

Once you’ve found Altair in the last of the glowing twilight, turn to the south, toward your left. Fomalhaut will be the next bright star you come to. Without any other even moderately bright stars nearby to act as signposts, it can be tough to spot, so be patient. But when you see it, there’s no doubt: It’s the only bright star in what’s an otherwise humble and quiet part of the sky. It’ll be at about the same altitude (that is, the same height off the ground) as Altair and will set around the same time.

Fomalhaut is a fairly young system about 25 light-years away. And that one point in the sky is actually three stars: Fomalhaut A is about twice the diameter of the Sun. When you look at it, you’re also looking at an exoplanet on a long orbit within a broad disk of dust, ice, and rock. In 2008, Fomalhaut b, also known as Dagon, became the first exoplanet discovered by direct imaging. Now, though, there’s some question about whether it’s a planet at all; it could be a “failed star,” called a brown dwarf. Either way, it’s incredible to think that we’ve been able to look across such huge distances and actually see a world orbiting another star.

Now that we have the first four stars on our tour in our pockets, let’s turn toward the east. For my dime, there’s no sight in the skies more incredible with the unaided eye than the enormous Winter Hexagon. Between the stars that make up the Hexagon, and the stars and clusters within and around it, I feel like a kid again every time I see it, even after all these years.

The Winter Hexagon wraps six first-magnitude stars together like a giant present in the sky. Aldebaran and Capella are already in the sky at sunset. It’s fun to pull back the curtains to check in on them and watch the rest fill the sky as the night goes on. Keep an eye open and watch Orion, the Hunter, rise with them, his shield leading the way, as he holds off Taurus, the Bull, for another night.

Sirius is the last of the Hexagon’s stars to rise. It’s, unmistakably, the brightest star in the night --more than twice as bright as the second-brightest star, the southern star Canopus, and it easily outshines everything else in the nighttime sky except the Moon, Venus, and Jupiter. The Sirius we see is actually a pair: Sirius A, a white star about twice the size of the Sun and Sirius B, a dim companion star . Sirius is also called the Dog Star, and, so Sirius B is sometimes called “The Pup.” That’s because it’s a white dwarf that has about the same mass as the Sun squeezed into the diameter of the Earth.

Gary Seronik

Sirius culminates, reaching its highest and southernmost point in the sky, right around midnight on New Year’s Eve, just as the confetti falls. Every year, I like to grab a friend or my kids and step outside just before the horns blow to have a look.

Counterclockwise around the Hexagon are golden yellow Capella, Pollux, Procyon, Sirius, icy blue-white Rigel, and orange Aldebaran. I like to include Castor,Pollux’s twin brother, along with them. It’s not a first-magnitude star, but it rounds the hexagon out into a circle and gives a really pleasant and soothing rhythm to the stars’ names. Try saying it and you’ll see.

Hiding just beyond the names and the bright lights, there’s a wonderful secret that seems fitting as we look back on the year. With the exception of Rigel, which is about 700 light-years away, all of the stars on the Hexagon are actually fairly close by. Sirius is only about eight light-years away, so if you have a third-grader handy, you can tell her that the light from Sirius she’s seeing tonight left on its voyage to her eye right around the time she was born.

One by one from there, the distances to these stars act like a list of milestones in a person’s life. Procyon is 11 light-years away. Its light is about the age of a kid starting middle school. Pollux is 34 light-years, around when people are setting into their careers. Capella, high above in Auriga, is about 42 light-years away, inching toward mid-life. Aldebaran, the farthest of the rest, is 65 light-years away, the age of retirement.

While we’re here, don’t forget bright orange Betelgeuse, right in the middle of Hexagon. With it and Rigel, Orion is the only constellation in the northern sky with two first-magnitude stars.

Just like that, we’re up to 11, and it’s not even midnight!

If it’s not too cold, and if you have a few extra minutes, stay outside a little while, and let your eyes adjust to the dark. Aldebaran appears to be in a V-shaped group of stars. That’s the Hyades, the closest star cluster to Earth, about 150 light-years away. Aldebaran isn’t part of the cluster, it’s actually in front of it from our perspective. West of the Hexagon, look for the Pleiades cluster and see how many of the Seven Sisters you can count. Oh, and don’t forget to look for the cloudy Orion Nebula in the middle of Orion’s sword.

NASA / ESA / STScI

These sights are beautiful with the unaided eye but if you have a pair of binoculars, they’re spectacular. The Pleiades is my favorite thing to look at in the entire night sky, and I love to pick out the far-away Trapezium cluster in the middle of the Orion Nebula’s dust.

3… 2… 1… Happy New Year! As we greet the first few minutes of the year, you can run back in from the cold having already found 11 of the north’s 15 first-magnitude stars!

The last four will take some planning, but even though it’s getting late, we’ll start the New Year off right.

...and on we go. Right around the same time the Winter Hexagon culminates in the south, the three stars of the Spring Triangle start to show their faces in the east. Regulus is first. I always think of the little king as something like the groundhog of stars. When I see Leo staring back at me on a mid-February night, I know warmer weather is just around the corner. Spring is still a long way off, though. Here in the first few days of winter, Regulus rises around 8:30 p.m. local time, but it might not be high enough above the rooftops to see easily until the middle of the night.

Regulus is the dimmest of all of the first-magnitude stars, so it might not jump out at you at first. It’s helpful to look for it at the bottom of the backward-question mark-shaped “sickle” asterism at the front end of Leo, the Lion.

One of my favorite stars is Arcturus, in Bootes, the Herdsman. It joins the fun a bit after midnight. Arcturus is the fourth-brightest star in the entire night sky, and the second-brightest visible in the north. It’s a red giant about 37 light-years away that has aged off of the main sequence. That means it’s moved on from fusing hydrogen in its core. Billions of years from now, our Sun will grow into that same type of star when it, too, has used up all of its hydrogen fuel and has started to fuse helium. In a way, looking at Arcturus is like looking at our own future.

Around 1:30 a.m. on New Year’s Morning, Spica rises, though it takes a little while before it’s high enough to see. And now we’re up to 14.

Well, we’ve done it. We’ve just about reached the end of our tour. The last star left is the bright-red supergiant Antares. The heart of the Scorpion takes some real commitment because it doesn’t rise until just before the start of dawn, around 5:30 a.m. on New Year’s morning.

Like Fomalhaut, Antares never gets higher than about 20 degrees above the horizon. Most of us are used to seeing it in July and August, bright, red, and fiery, so it might be a little confusing and unsettling to see the Scorpion sneaking through a cold morning. It’s always fun to see stars out of season, though, isn’t it? You’ll need to look fast before the Sun rises and washes it away. Maybe try to see it in the morning on December 31st. That way, you get two chances. Plus, you’ll probably have the morning all to yourself, before the noise of the day starts.

I don’t always get them all, but the holidays just wouldn’t be the same if I didn’t at least try to see these 15 stars. Whether you’re new to the skies or have been watching for decades, it’s a great way to spend the New Year with some old friends.

I hope you enjoyed this tour of the night sky from Sky and Telescope. I’m Scott Levine. Happy New Year!

3

3

Comments

Rod

December 31, 2020 at 2:40 pm

Good use of MS WWT video ability here, thanks. I use MS WWT as well as some other tools like Stellarium and Starry Night. MS WWT images can be very good and useful---Rod

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Scott Levine

January 15, 2021 at 12:37 pm

Hi, Rod, Sorry for not getting back to you sooner. The WWT work is really incredible isn't it? They did a great job. I'm glad you liked the video.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

planetmatter

September 16, 2022 at 12:54 pm

I can hardly see the stars in this video, the red outline of constellations is confusing. Perhaps it's due to my laptop, but it is on the brightest setting. The still images in the transcript look great. Maybe you can adjust the settings. In any case, the tour was wonderful! Thank you.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.