And that makes three: Astronomers are beginning to understand what may be causing a special kind of flare in the distant universe.

And you thought gamma-ray bursts were spectacular!

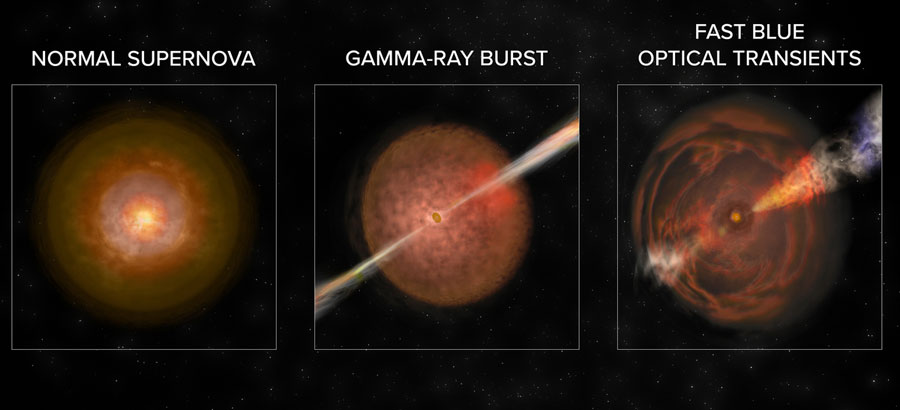

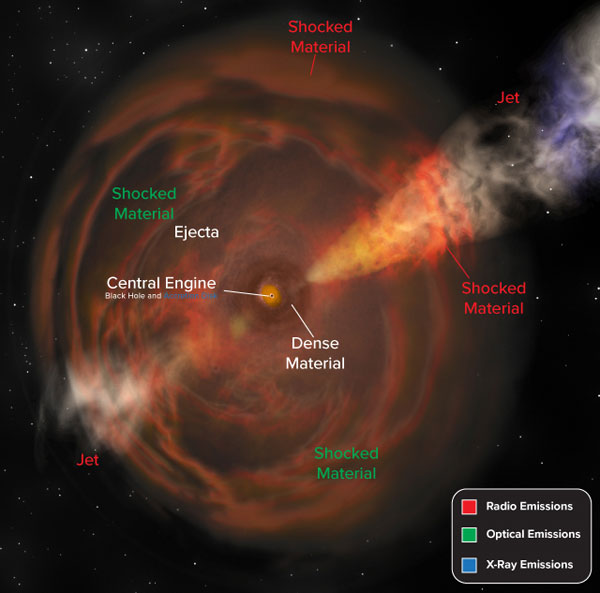

Well, they are: Those titanic stellar explosions vastly outshine complete galaxies and shoot out tenuous jets at near-light speed. But a new class of objects, known as Fast Blue Optical Transients (FBOTs) for their rapid flares and blue-hot color, compare to gamma-ray bursts as dinosaurs compare to jaguars. The jets they produce are slower, shooting out at about half the speed of light. But they can also be 10,000 times more massive, carrying up to 10% of the Sun’s mass.

Bill Saxton / NRAO / AUI / NSF

Introducing the Menagerie

Radio observations revealed these properties in one explosion known as CSS161010, which occurred in a dwarf galaxy some 500 million light-years away in the constellation Eridanus. Brightening to a peak in just a few days, the burst was discovered on October 10, 2016, by the automated Catalina Sky Survey and, independently, by the All Sky Automated Supernova Survey (ASAS-SN). Deanne Coppejans (Northwestern) and colleagues carried out follow-up studies of the blast with the Very Large Array in New Mexico, the GMRT radio telescope in Mexico, and NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, publishing the results in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

CSS161010 resembles another stellar explosion, discovered by the ATLAS survey on June 16, 2018, 200 million light-years away in Hercules. Researchers presented observations in early 2019 of this weird, extreme supernova, officially known as AT2018cow but quickly nicknamed “The Cow.” In the case of CSS161010, however, “it took almost two years to figure out what we were looking at just because it was so unusual,” according to coauthor Raffaella Margutti (also at Northwestern).

Meanwhile, the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Mountain (California) had bagged another luminous burst. That brings the total number of extremely energetic FBOTs to three. Officially the event is ZTF18abvkwla, but astronomers soon nicknamed it “The Koala.” (Soon there may be a whole zoo!) ZTF's telescope recorded the event on September 12, 2018, in a dwarf galaxy 3.4 billion light-years away in the constellation Aries, the Ram.

Follow-up radio observations, this time by Anna Ho (Caltech) and colleagues, revealed that the explosion launched a fast-moving outflow. The collision of that outflow with ambient gas and dust produced bright radio-wave emission rivaling gamma-ray bursts in luminosity." In their paper, Ho and her colleagues also conclude that FBOTs are “at least two to three orders of magnitude less common” than core-collapse supernovae.

Bill Saxton / NRAO / AUI / NSF

A New Kind of Supernova?

So what are these “new beasts,” as Margutti calls them? Most astronomers believe they are indeed massive stellar explosions, like gamma-ray bursts, leaving neutron stars or black holes in their wake. But in the case of FBOTs, thick, dense clouds of material surround the exploding stars, possibly formed as the result of interaction with a binary companion. Another technical difference is that FBOT spectra contain signatures of hydrogen and helium. Gamma-ray burst spectra do not, probably because the progenitor star completely lost its hydrogen-rich outer envelope at an earlier stage.

Still, there may be a connection. Ralph Wijers (University of Amsterdam), who was not involved in the new studies, believes there could be a continuum between regular supernova explosions and the most energetic gamma-ray bursts. “It looks like these FBOTs, with associated radio and X-ray emissions that indicate mild relativistic outflows, might well fill in part of the gap,” he says.

Yet another clue to FBOTs’ true nature may be found in their host galaxies. In all three cases mentioned here, Keck Telescope spectra revealed that the blasts occurred in puny galaxies with a high star formation rate. The low abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen or helium in dwarf galaxies may have influenced stellar evolution in some uncommon way, enabling these rare explosions. Alternatively, FBOTs may represent so-called tidal disruption events, where unlucky stars are ripped apart and consumed whole by intermediate-mass black holes.

While the jury is still out on what produces these hot, brief, and energetic outbursts, one thing’s for sure: Now that astronomers know what to look for, many more will be found in the years to come. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory could potentially find lots of them when it becomes operational in 2023. However, Wijers warns that the observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time might miss the fastest ones, because of its observing strategy.

In any case, CSS1610, The Cow, and The Koala are just the tip of an explosive iceberg.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.