Amateurs celebrate the venerable space telescope’s 30th anniversary with a look at some of its most mesmerizing images.

NASA

For 30 years, the Hubble Space Telescope has been a powerhouse of discovery for professional astronomers. But behind the scenes are some amateur astronomers, too. We are among the hundreds of dedicated scientists, engineers, managers, and others who have kept the venerable spacecraft operating and its cosmic revelations flowing over the past three decades. And to share Hubble’s sharp vision from space, we sometimes rely upon insights gained from stargazing on Earth.

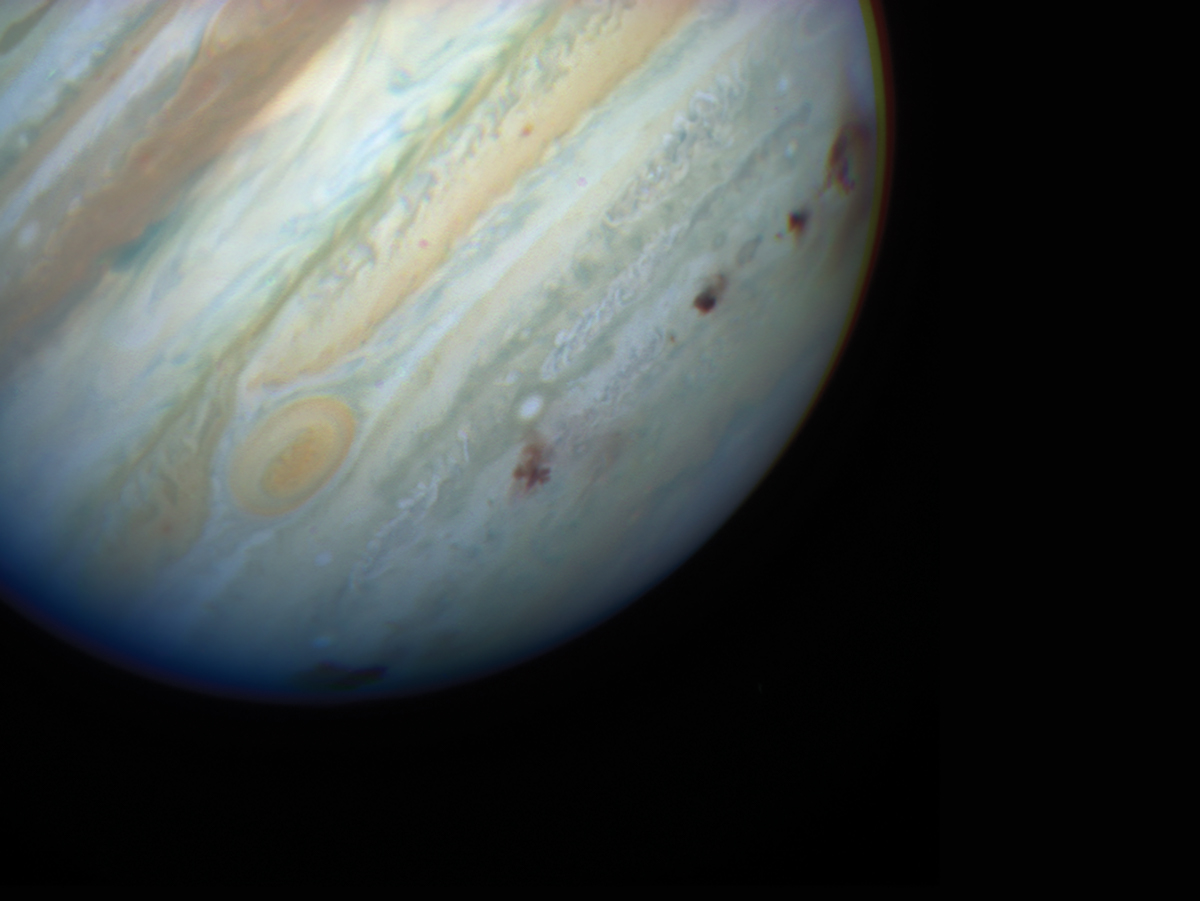

I was in junior high when Hubble launched aboard Space Shuttle Discovery. Back then, the many nights I spent stargazing during family camping trips in northern Michigan had just begun to develop into a deeper curiosity about the universe. It wasn’t long before I decided that I wanted to be an astronomer. The summer before heading to MIT for college, I was awestruck by Hubble’s images of the giant, black scars Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 left on Jupiter. Never would I have imagined that, decades later, Hubble would still be wowing me and that I’d be at NASA, telling the ongoing story of the telescope and its discoveries.

NASA

But I never became a professional astronomer. Midway through college, I loved astronomy more than ever, but I feared that I had neither the stamina nor the finances to spend several more years obtaining a PhD. Instead, I paired my passion for astronomy with a knack for writing and became a science writer. I’ve been with the Hubble team since 2006, involved in crafting articles, videos, social media posts, handouts, books, media campaigns, public events, and anything else NASA’s Hubble outreach team creates to share the telescope’s accomplishments with the world.

I’ve sustained my bond with the universe as an amateur astronomer, though — shivering in remote fields while counting streaks cast by the latest meteor shower, camping out at star parties around the country to marvel at the dark skies, and hunting down every Messier object with my trusty Dobsonian. I’ve held positions in local astronomy clubs, and I share views of the night sky with everyone I can at outreach events.

My experience as an amateur occasionally comes in handy at work, too. When Hubble is releasing a new image of a celestial object that’s visible in the night sky, for instance, the communication team frequently turns to me to find out if and when amateurs could spot the object, what equipment is needed to see it, and what it might look like from a suburban backyard, so we can share that information with the public. And when NASA provided telescopes for Astronomy Night at the White House in 2009 and again in 2015, my colleagues selected me to attend because I could operate a telescope and locate interesting targets, even in the light-polluted skies of Washington, DC.

NASA

Specs

The Hubble Space Telescope is 13.2 meters (43.5 ft) long, the length of a large school bus. Its primary mirror is 2.4 m in diameter and weighs 828 kg (1,825 lb).

I’ve been fortunate to find other amateur astronomers on the Hubble team — kindred spirits who know the night sky and appreciate what some of the celestial objects in Hubble’s remarkable images look like through ordinary telescopes on the ground. One of them is Kevin Hartnett, who oversees the mission’s science operations conducted by the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI). Kevin was hooked by astronomy as a kid, too — in his case by a friend who was grinding a 6-inch telescope mirror. The two of them joined the Junior Astronomical Society of Harrisburg, staying out all night in sleeping bags to soak in the dark Pennsylvania skies.

NASA

Repairs

Hubble launched in April 1990 but with a primary mirror aberration that blurred images. It wasn’t until after the first servicing mission in 1993 that astronomers could capture the pristine images the space telescope is famous for. Astronauts completed five Hubble servicing missions between 1993 and 2009.

Kevin caught the astrophotography bug early and continued to develop his skills while studying physics and astronomy at the University of Delaware, completing a project to image Comet Kohoutek. Like me, Kevin opted out of the PhD route, instead working in private industry after graduation. He made his way to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center as a mission operations contractor before being offered a job as a NASA employee the day before Hubble’s launch in 1990. He joined the Hubble team in 1997, right about the time I was shifting my aspirations from becoming a professional astronomer to writing about astronomy.

Kevin spends many hours teaching others about the heavens, hosting star parties, and photographing the sky. Since purchasing a DSLR camera five years ago, he has contracted astrophotography fever. At Goddard, Kevin’s images of the night sky hang alongside Hubble’s grand views on conference room and cafeteria walls. We’ve even compared Kevin’s photos of some celestial objects to those targeted by Hubble so we could assess the view from his Maryland backyard relative to Hubble’s view from orbit, 540 km (335 miles) up.

NASA

Kevin Hartnett

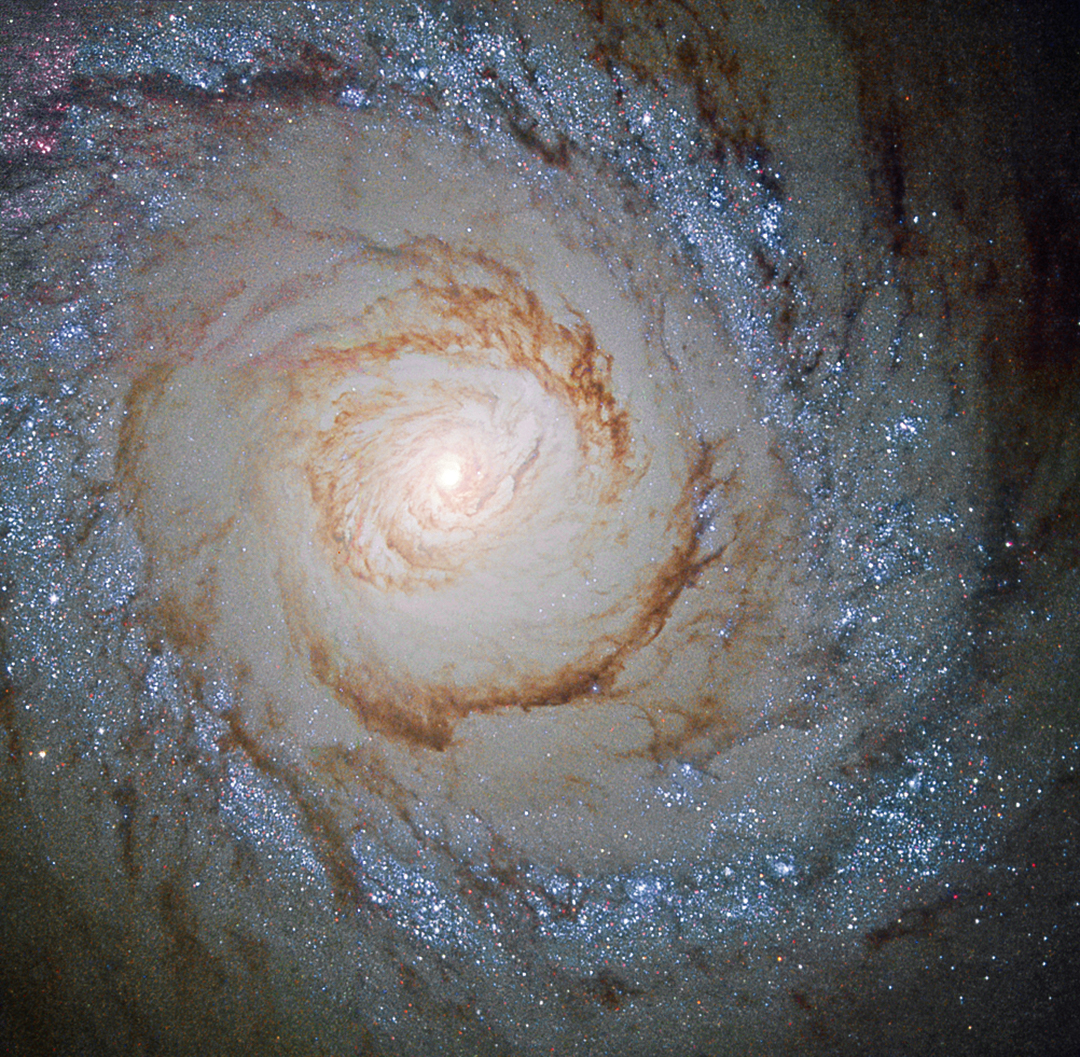

Kevin and I are both active members of the Goddard Astronomy Club, a small but enthusiastic group of amateur astronomers who work or once worked for NASA in a variety of roles — from engineers and scientists (including a couple of professional astronomers) to programmers, IT specialists, managers, and outreach professionals. Kevin and I have even recruited other members to help us out with projects at times. For example, we’ve put our amateur hats on to assemble online collections of Hubble images taken of objects from the Messier and Caldwell catalogs, so that other backyard astronomers could compare their views to Hubble’s. We’ve used our observational knowledge to explain when and how others can see these objects themselves and to create basic star charts to accompany Hubble’s images. I believe our experience as amateurs provides perspective, helping us better explain why Hubble’s crisp views from above the atmosphere are so vital to astronomy and advancing our understanding of the universe.

When Kevin gives tours of Hubble’s control center and describes Hubble’s images, for example, he often shares his own photos of the same objects imaged by Hubble and tells visitors when they could view these things in the night sky. We’ve both found that when members of the public find out that they can see some of the same objects Hubble has, it heightens their interest in the telescope and its observations. Reviewing some of Hubble’s images has also inspired us to venture outside to revisit these objects or view them for the first time with our own eyes.

Fuelless Pointing

The space telescope has no thrusters. To change angles, it uses Newton’s third law of motion: It spins its four reaction wheels in the opposite direction it wants to go, and the combined torques point it at any location on the sky. The telescope takes 15 minutes to turn 90° — the speed of the minute hand on a clock.

NASA

Kevin attests that much of what he’s learned as an amateur astronomer — from names and nomenclatures to facts and figures to general astronomy concepts — aids him in his daily work. This includes understanding and evaluating decisions made by STScI in matters ranging from scheduling the telescope to calibrating its instruments. In one instance, Kevin’s familiarity with Messier objects helped when the calibration group needed to find a large open cluster in the spring sky after their go-to cluster for calibration, M35, slipped into Hubble’s solar avoidance zone. (This is a region of sky 54° in radius around our star that the space telescope can’t observe, lest its optical tube heat up dangerously.) Kevin was able to quickly recommend M44 or M67. He says that a firsthand knowledge and familiarity with CCD astrophotography has

also taught him the importance of the calibration frames that STScI uses to process Hubble’s images.

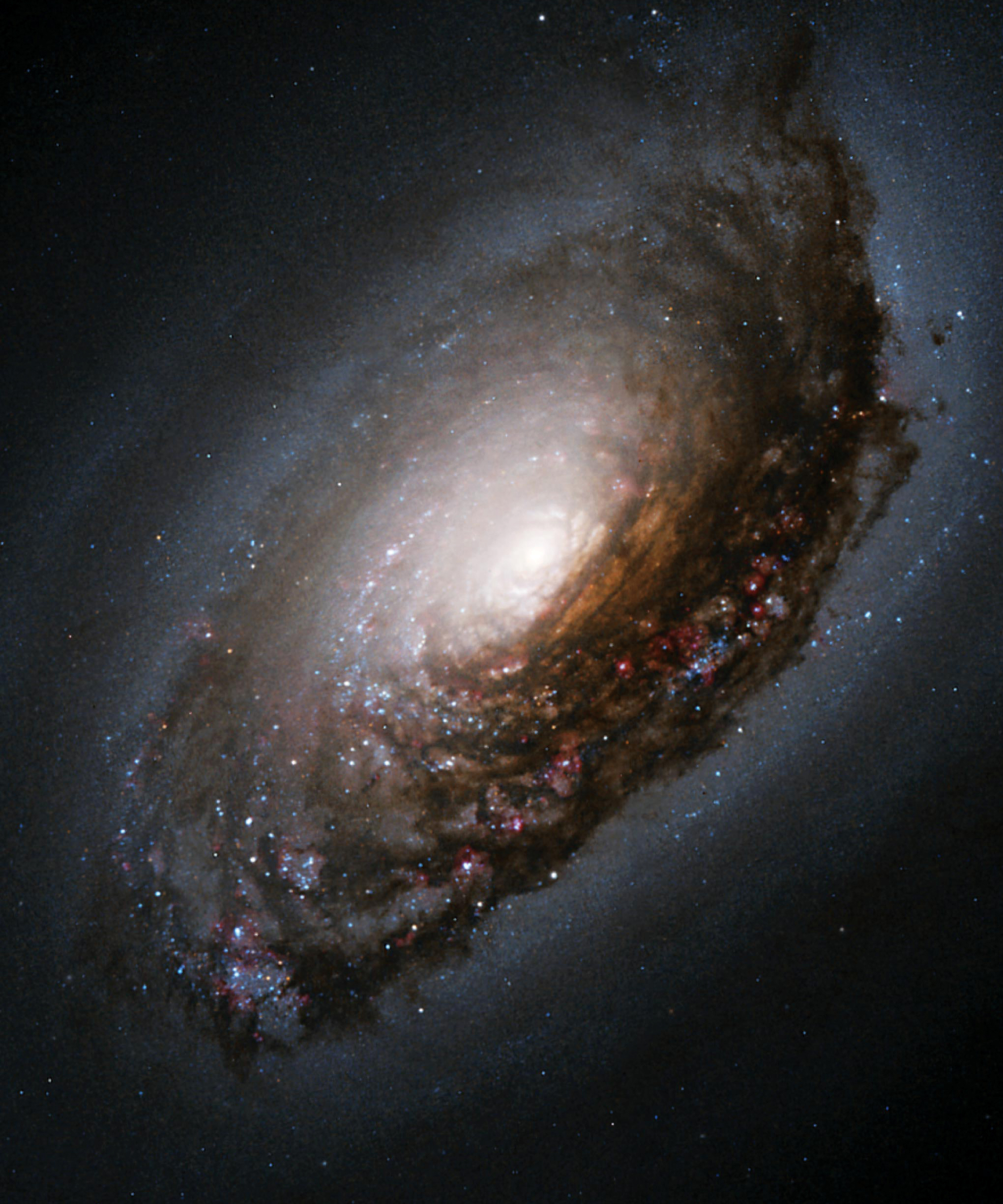

Looking back at Hubble’s 30 years (and onward to the future), I can’t help but feel that Hubble’s story and mine have been intertwined, and not just because I work on the team. Hubble has had an effect on us all. It has revolutionized the way we understand the universe, permeated our culture, and even changed the way we think about the cosmos. I know when I think of the Crab Nebula, for example, I don’t immediately think of the small, oval fuzz of light in my eyepiece — I visualize Hubble’s fantastic, colorful visage of tangled threads of glowing gas. I see the universe through Hubble’s eye. And from views of the universe in sci-fi movies to imaginative works of art, it’s clear that others do, too. I’d be surprised if Hubble hasn’t made some kind of impact in the life of every astronomy enthusiast around the planet it orbits.

We hope you enjoy the images we’ve shared with you on these pages as much as we do, and that they might inspire you to go outside and observe the night sky, too.

NASA

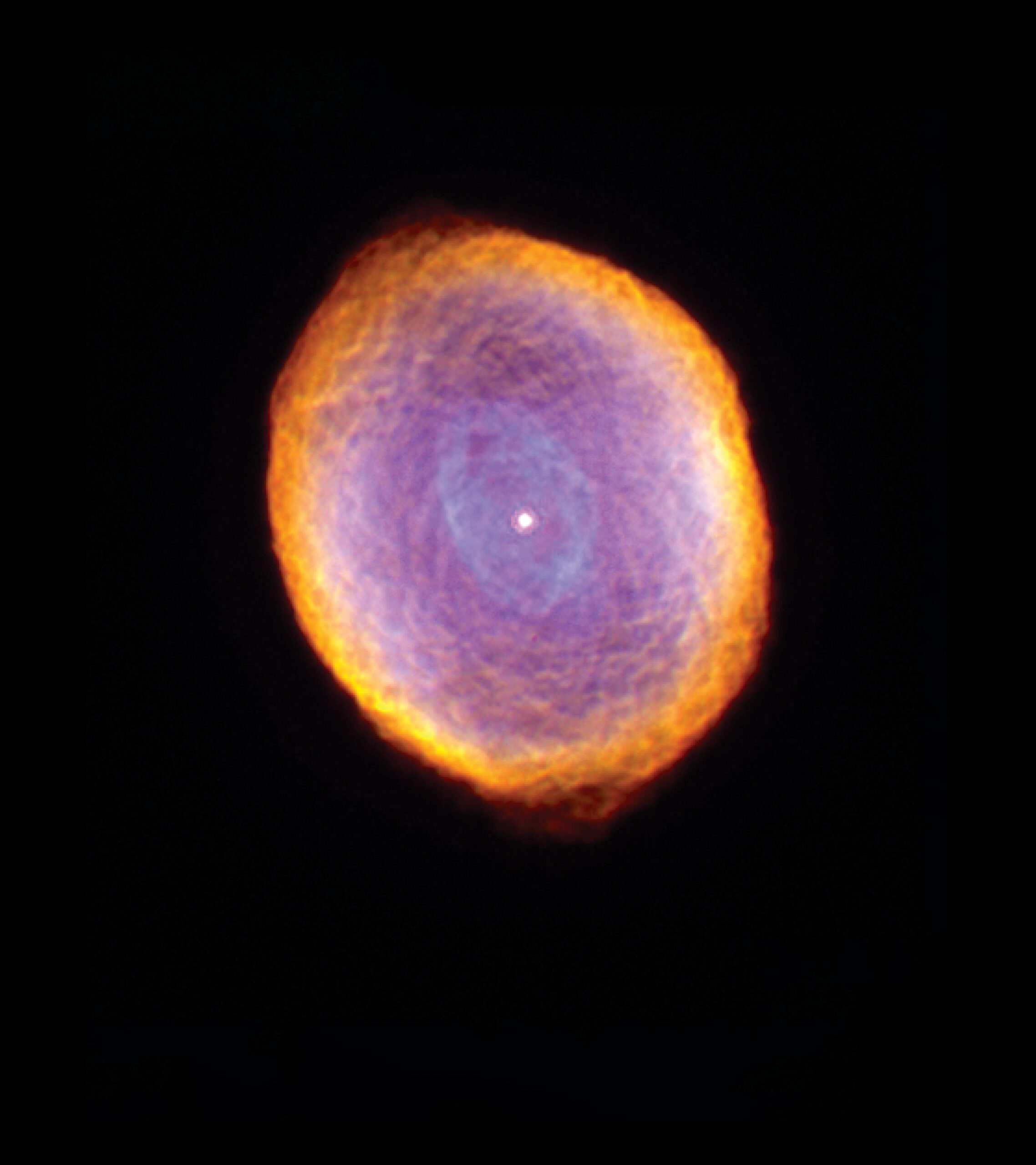

NASA / ESA / Hubble Heritage Team (STSCI / AURA)

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Sky & Telescope.

1

1

Comments

Peter Wilson

April 24, 2020 at 3:02 pm

Nice!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.